Introducing Human Factors into Scientific Diving: first impressions

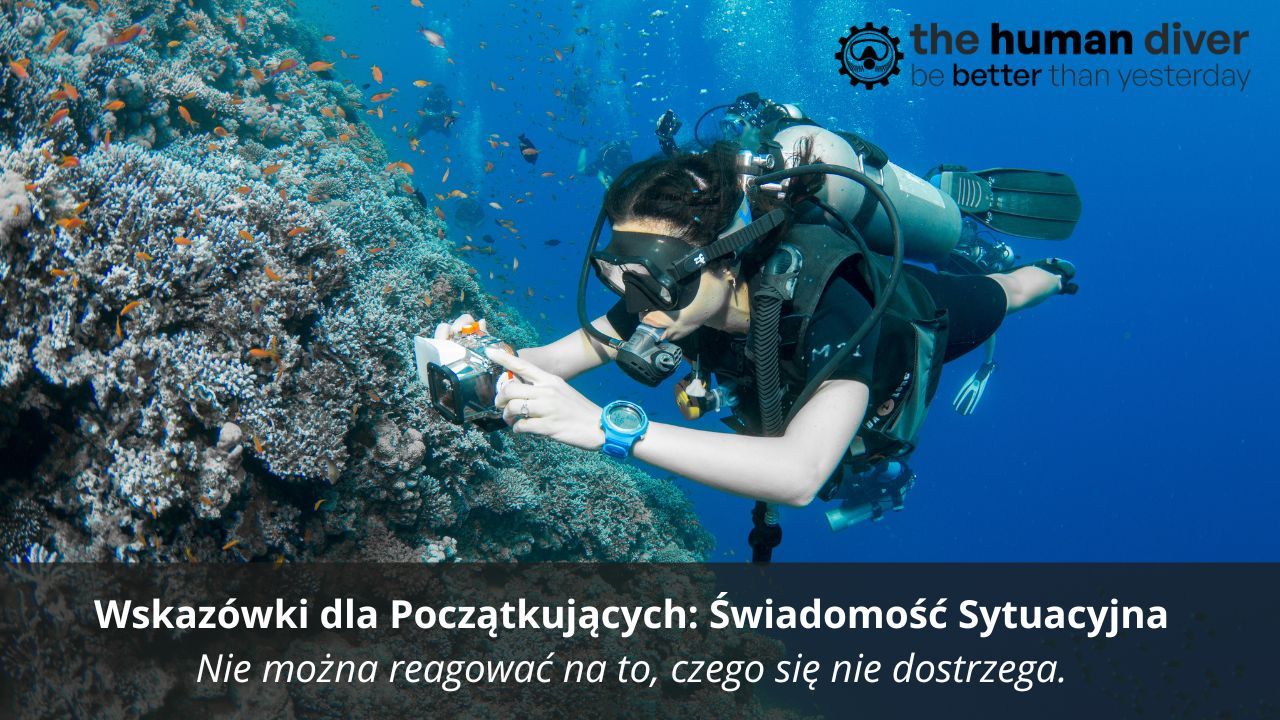

Mar 05, 2023As divers, we all know that diving can indeed be a complex and challenging activity. The role of human factors in diving is critical and, nowadays, undeniable. The community is gradually starting to realise the impact that they can have on safety and performances, and it’s not so uncommon to hear words such as “decision making”, “effective communication” or “situation awareness”, among the diving circles now.

I personally started my path into the human factors field a few years ago and never regretted it once. That’s why, when Edd Stockdale asked me to assist him with the first Occupational Scientific Diving Training class at the Tvärminne Zoological Station (Finland), I was sure we were going to include these concepts in the program.

What is "scientific diving"?

Scientific diving is a specialised form of diving whose primary goal is to conduct research and collect data in the underwater environment. It is used by a wide range of professionals, including marine biologists, oceanographers, archaeologists…and many more.

The wide range of techniques and tools used is such that knowing all of them would require years of training in too many different environments around the world. At the same time, a scientific diver often needs to be able to conduct equipment maintenance and repair, carefully plan underwater research in a safe and effective manner, and be able to act as a first responder. Because of the nature of the job, every project can be different from the previous one, making it harder to follow a fixed scheme. While this creates space for innovation and changes, it can also easily lead to slips, omissions, miscalculations and so on.

After seeing the difference that basic knowledge of the role of human factors had on the students of our traditional diving classes, it was clear to both of us that this kind of training had to be included in the scientific diving class as well.

The class took place from the beginning of August to the end of September in the astonishing Hanko peninsula. The Tvärminne Zoological Station is situated in its beautiful archipelago and is also the base for the FSDA (Finnish Scientific Diving Academy), whose main goal is to train European-recognised scientific divers and grow a new generation of marine scientists.

Eight students from all around Europe joined the first program, which aimed to introduce and develop skills in all the areas of running scientific diving projects, supervision and management of dive teams, emergency plans and diving skills.

We asked the students to complete the Essentials online training before the beginning of the course. Then, on the first day, we delivered a 2-hour lecture to make sure that all the main concepts were understood and to explain how we wanted to incorporate them into the class.

The effects had been evident since the very beginning and definitely improved the quality of the training for everyone.

An example of this was focusing on a psychologically safe environment, to make sure that students felt comfortable in sharing their doubts, questions or difficulties with us and between themselves.

Some of them had less underwater experience and asked the others to review the skills in the evening after the class. This made sure that nobody was left behind and they all helped each other along the way, growing and evolving as members of a bigger team.

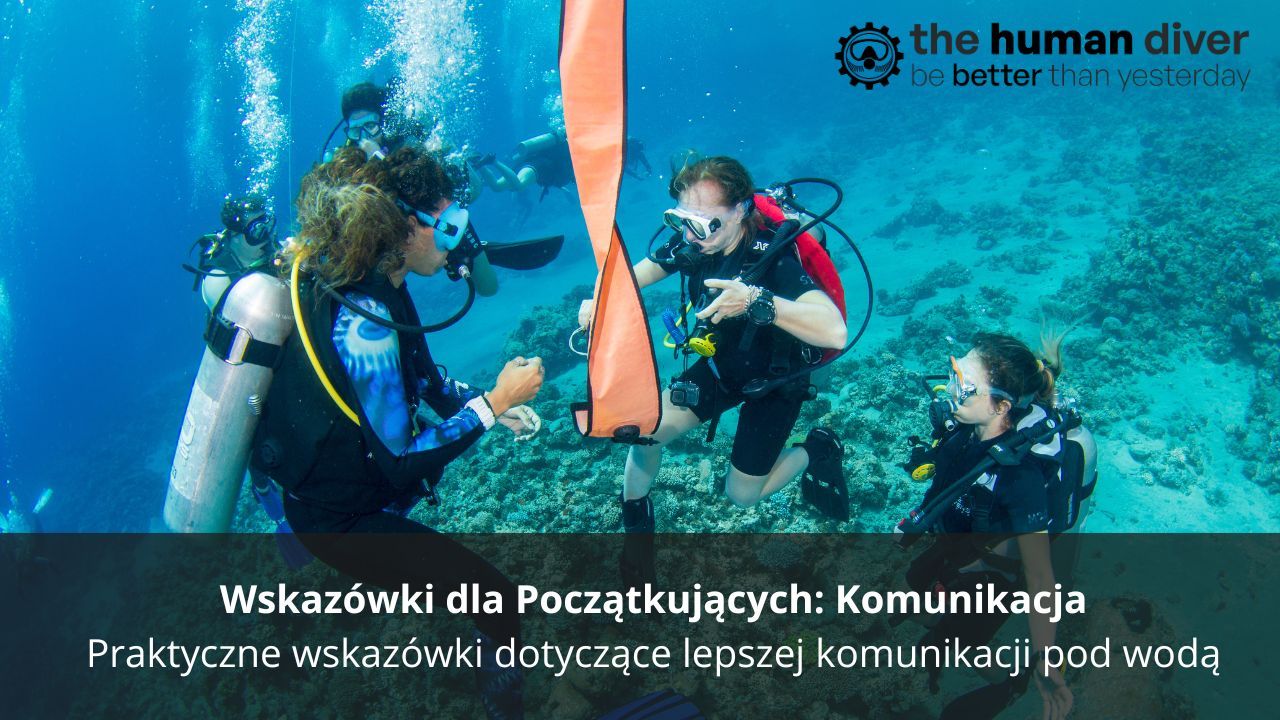

We also implemented checklists and worked on effective communication techniques, especially because the participants were coming from different countries, with different ages and a variety of scientific and diving backgrounds.

Boat checklists helped them realise they were missing some tools before heading out, and pre-dive checklists highlighted disconnected drysuit hoses and forgotten weight belts or cutting devices. These situations were easily spotted and fixed while still on the shore, or on the boat, with a minor delay in the whole operation.

Overcoming the barriers that existed because of the different mother tongue language was another step.

While getting trained on the use of the FFMs and their communication system, they faced the struggle of understanding different accents and broken words because of background noises or unclear transmissions. Working on effective communication techniques and agreeing on a communication protocol helped them overcome these obstacles and led to using these tools for most of their projects.

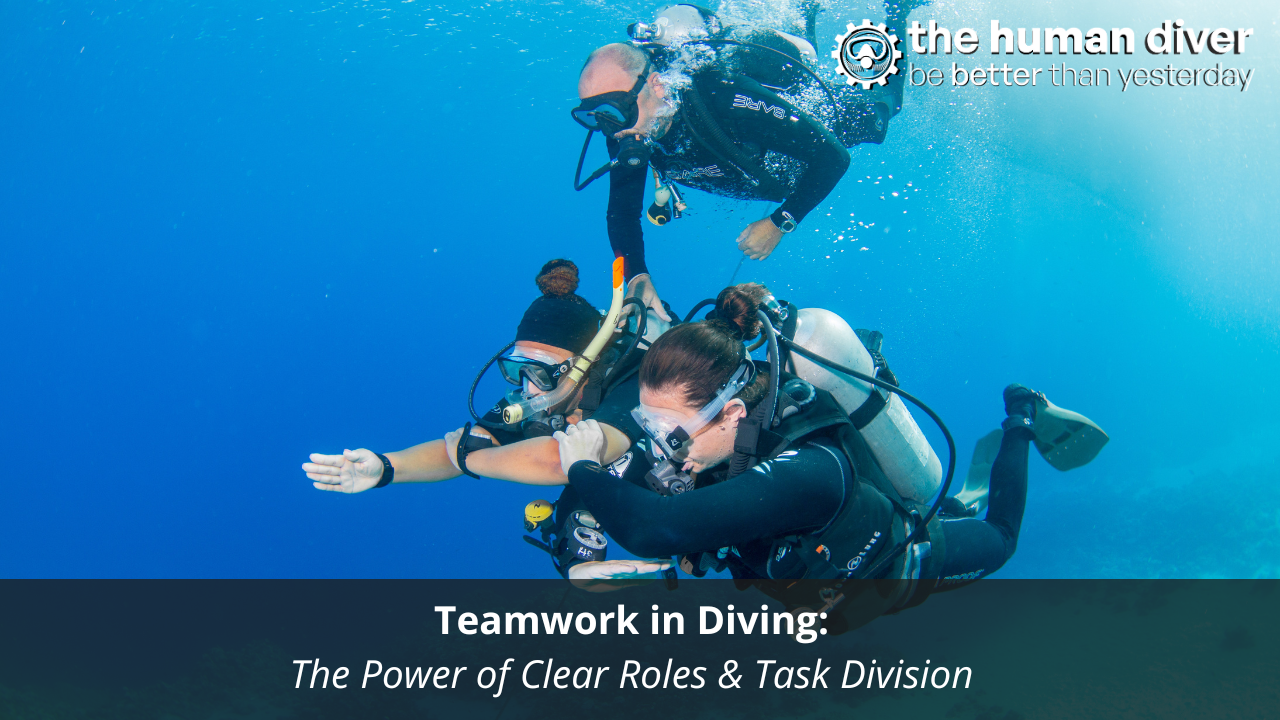

They found out that by asking questions and ensuring that communication had effectively happened, they were spending a few more minutes briefing before starting the activity but, in the end, they were operating much more efficiently underwater. Their role clarity was enhanced and they rarely had to repeat an action because of misunderstandings, which in the end saved time, effort and economic investments. On the plus side, the quality and quantity of their data and samples collection clearly improved.

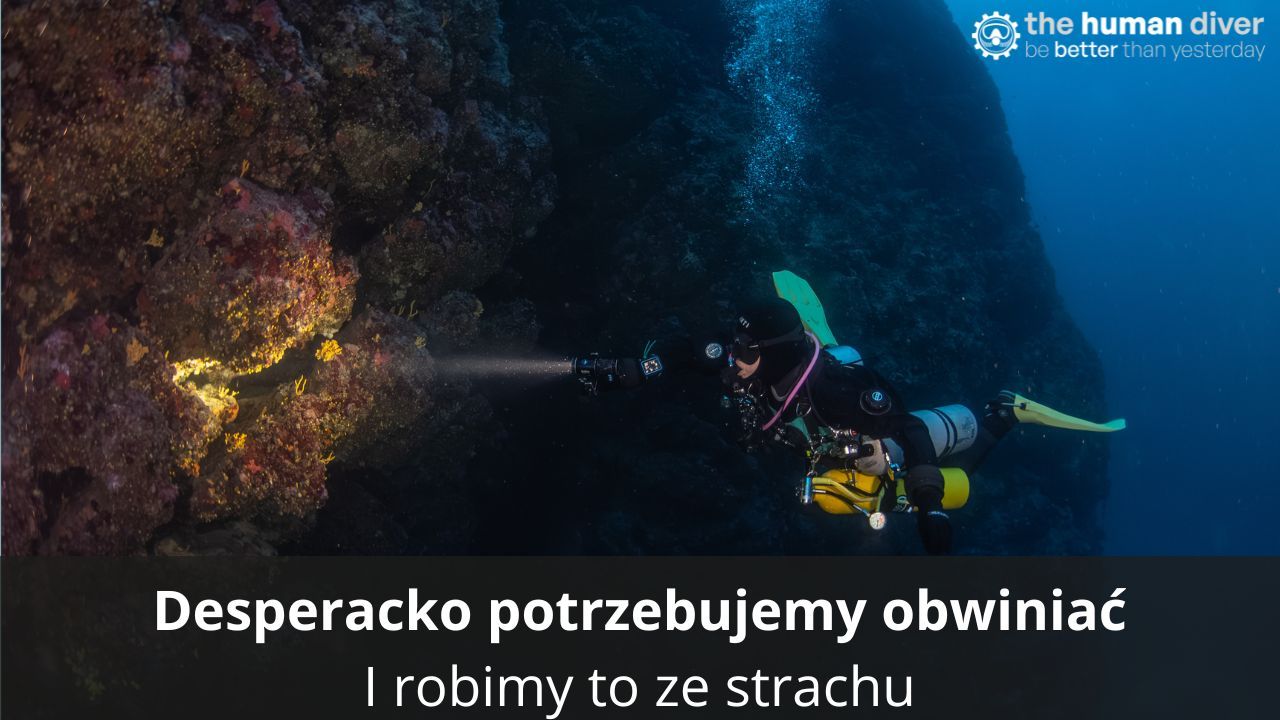

Another reason to introduce the human factors training was to cover the topic of stress and fatigue and how external psychological and physical factors can affect the work environment and compromise safety and efficiency. The intense training schedule and long hours during the 6 weeks of the course had been enough to create different situations of disagreement and conflicts, which they learned to handle in a constructive and positive way.

If any of them was not feeling comfortable performing the dive because of fatigue or stress, it was shared with the team and they ended up adjusting the roles or re-organising the work not to compromise safety, without excluding or blaming the person.

The evening debriefs, which were happening every day, were moments of reflection for both us as instructors and the students. They could ask additional questions and discuss the daily activities to highlight what went well and what went wrong, or not so well. In the end, they were coming up with suggestions and revised plans for the next day's projects. Because they were sharing, they always gained something from someone’s else experience and this process led them to gradually, but constantly, improve every day.

Overall the addition of the human factors module into the training had a major impact on the whole class, improving their safety and performance, as well as reducing the risk of accidents and errors. But, most of all, as they all said at the end of the class: it helped create a great learning environment in which they felt comfortable sharing doubts and asking questions.

In the end, after 6 weeks, they went from being a group of strangers to being an efficient and proficient scientific diving team. Needless to say, we are so proud of their development.

Beatrice is an active open circuit and CCR technical instructor. She holds a Master's Degree in Marine Biology and Oceanography and co-authored the book "Biodiving: Environments and Organisms in the Mediterranean". She traveled the world diving and teaching in different environments and she is now working as a Diving Safety officer for the NYUAD. Beatrice can be contacted at https://www.facebook.com/zeroemissionsub/

Beatrice is an active open circuit and CCR technical instructor. She holds a Master's Degree in Marine Biology and Oceanography and co-authored the book "Biodiving: Environments and Organisms in the Mediterranean". She traveled the world diving and teaching in different environments and she is now working as a Diving Safety officer for the NYUAD. Beatrice can be contacted at https://www.facebook.com/zeroemissionsub/

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.