Top Tips for Beginner Divers: Decision Making

Aug 13, 2025How many decisions are present on this dive?

Two 'Advanced Open Water' divers with less than 20 dives each took part in a wreck dive in 16 metres in Scapa Flow from a liveaboard boat. The current was discussed during the dive brief, during which it was highlighted that it would be quite strong when outside of the short slack window. One of the divers, James, wanted to take some photos of the wreck, replicating images he’d seen, and this was one of the goals for him on this trip to Scotland.

Around 30 minutes into the dive, James was focused on framing the wreck in the clear visibility, working hard in the current to remain in place. Once he got the shot he wanted, he looked up and realised he hadn’t seen his buddy for some time. He also realised he hadn’t checked his SPG for a while and pulled it out to check. The pressure was much lower than expected. Instead of surfacing immediately because the current was strong, he swam in the direction he thought his buddy had gone, rationalising that they were both experienced enough to manage the situation. He couldn’t find them, and he was working hard to get back to the wreck against the current.

Torn between ascending and finding his buddy, James decided to get his new dSMB out, which he’d never used before. He managed to send it up, sorting out a few issues while he ascended, one of which was not realising how much line would be paid out in such a strong current. When on the surface, he realised he was a long way down-current, and just on the limit of surface visibility of the dive boat, given the conditions. The diver was picked up by the boat; their buddy wasn’t on the boat and had been blown further down the dive site by the current. The buddy hadn’t made it back to the wreck either.

Over a mug of hot chocolate, the pair debriefed the dive and recognised how fragile some of the assumptions they’d made had been. This outcome wasn’t due to an obvious lack of technical skills; rather, it was influenced by numerous cognitive processes, including assumptions, shortcuts and social conformance.

Why decision‑making fails more easily underwater than on the surface

Decision‑making during dives differs from many day‑to‑day ‘choices’ because of time pressure, sensory limitations, and physical constraints. Human factors research shows that diving incidents often arise from ‘poor’ decisions rather than technical failures. Novice divers are still building mental models of how to make sense of the situation, and act accordingly, and yet they must still make rapid judgments about whether to continue, abort or change a plan. There are a number of factors that make these judgments more prone to error.

Stress and cognitive workload

degrade our ability to process information. Cold water, unexpected currents or equipment concerns increase mental load, drawing attention away from key data such as depth or gas supply. In my story, fascination with photography and trust in the perceived calmness of the dive created a cognitive tunnel. Under stress, the brain relies on intuitive (System‑1) thinking; while fast, it is prone to oversights. Slowing down to engage analytical (System‑2) thinking is essential for safer choices.

Mistakes, slips and lapses: different types of human error.

A mistake occurs when we choose the wrong course of action, believing it to be right—like continuing a dive despite unknown gas levels. Slips are unintended actions, such as pressing the wrong inflator button in panic; lapses involve forgetting to perform an action, like skipping a buddy check. Human‑factors scholars note that each type has different causes and needs different prevention strategies.

We are all biased.

Cognitive biases distort our judgments. Sometimes this is a positive ‘thing’, sometimes it’s a negative one – in either case, we need to understand how and why the decisions we made make sense. Plan‑continuation bias and the sunk‑cost fallacy incline divers to press on because of invested time or effort, even when conditions change. Many novice divers hesitate to abort because they fear wasting a rare opportunity or disappointing a buddy. The more we invest (time, money, emotion), the harder it is to say no. Overconfidence is especially common among those with limited experience. This is because during diver training, they’ve been encouraged to overcome fears they might have, and this can lead some of them to underestimate the presence or severity of the hazards present. Recognising these biases helps break their hold.

Mismatched mental models: reality versus expectations

Mental models are internal representations built from past experiences and reflections, and not just about diving. Their main advantage is that they allow us to anticipate outcomes and act without much thought. We are efficient creatures, trying to minimise the amount of energy we expend, and that includes the energy needed to critically think about an activity.

For novice divers, these models are in limited supply and may be based on conditions encountered during training. These conditions might be ‘good’ or ‘poor’ – either way, they will influence behaviours. When the environment changes e.g., a stronger current or the diver uses a different piece of equipment, we may still use the same model, leading to inappropriate actions. Unless we deliberately update models through reflection and training, we may repeat the same mistakes.

We are social creatures. We want to conform.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that social dynamics influence our decisions. Novice divers may defer to more experienced buddies or instructors, assuming their decisions are correct. They may also refrain from calling a dive out of fear of being judged. Crew resource management (CRM) and non-technical skills literature/programmes emphasise the need for open communication and shared mental models to ensure all voices are heard. The presence and maintenance of psychological safety is a fundamental requirement to support this need to speak up when needed.

These performance influencing factors (PIFs) do not act exist in isolation - they interact. Stress amplifies biases and assumptions, and social pressures make it harder to question potentially flawed plans. To improve decision‑making, novice divers should understand how and why decisions happen in the way they do. By combining diving experiences and the knowledge surrounding decision-making, inexperienced divers can identify when they are more likely to make a sub-optimal decision and adjust their performance accordingly.

Tools to strengthen decision‑making

Pre‑dive briefing with decision points

Use a concise checklist tailored to your equipment and environment and include explicit “decision points” in your plan. For instance, decide ahead of time how much gas will trigger a turnaround and what signals you’ll use to abort. Checklists should have around five to eight items and be performed aloud to slow down thinking and reduce memory lapses. A clear plan gives you a ‘line in the sand’ when stress and biases start to cloud judgment.

Pause–breathe–reassess technique

When you notice stress or uncertainty, stop moving, take a few slow breaths, and reassess your gauges, surroundings and buddy’s location. Consciously shifting from automatic actions to analytical assessment breaks the cycle of plan‑continuation bias and prevents panic. Practise this on easy dives so it becomes automatic when needed.

Routine scanning and mutual monitoring

Develop a scanning pattern, depth, time, gas, navigation and team-mate, and repeat it regularly. Agree that everyone has the authority to call the dive without question. Mutual monitoring helps catch slips and lapses; it also counters overconfidence by keeping everyone accountable.

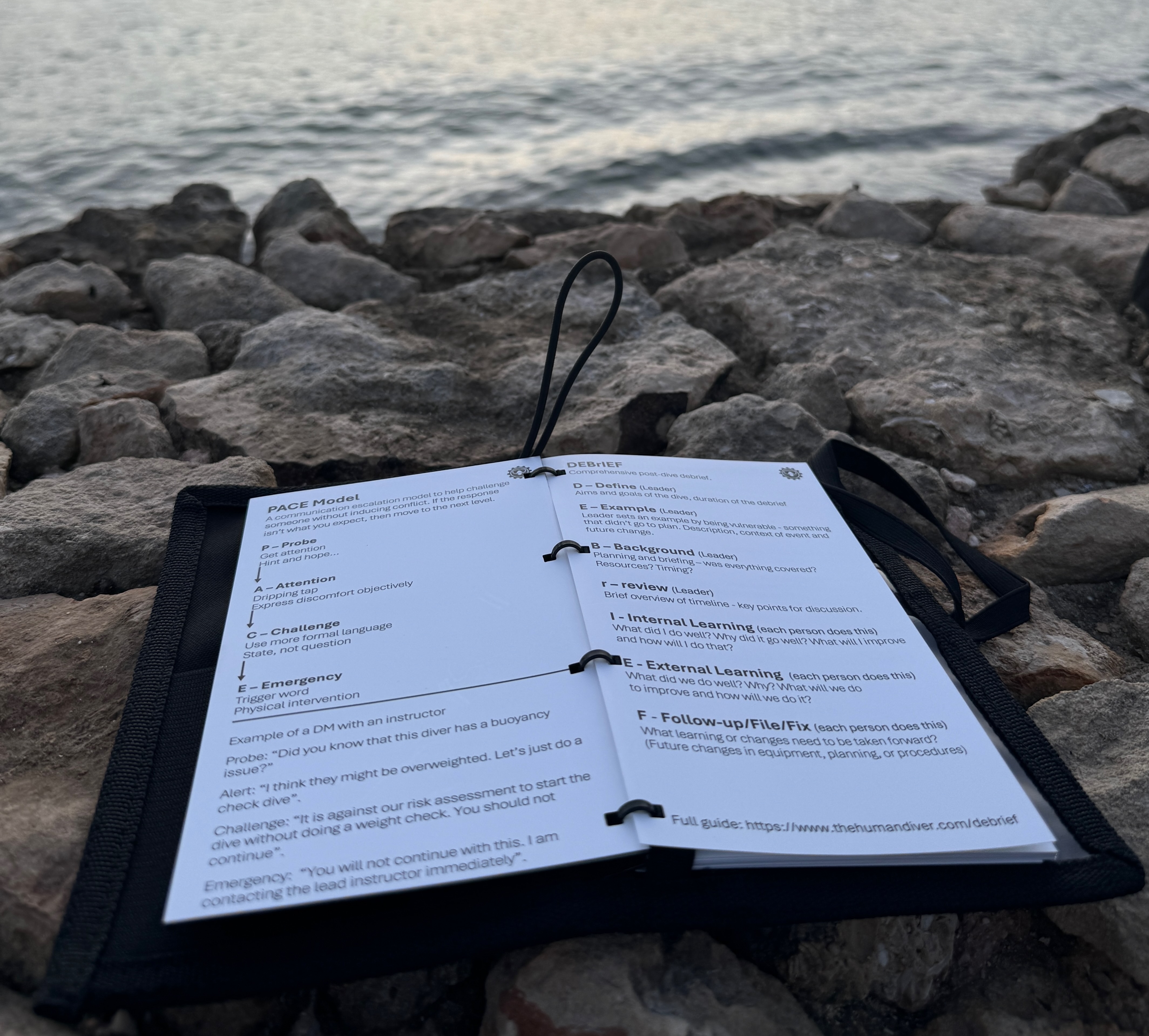

Structured post‑dive debrief

Reflection allows experience to move into improved mental models. Using a framework like DEBrIEF allows a structured discussion around: the goals/aims of the dive, creating a non‑judgmental environment, comparing the plan against the reality, encouraging personal and team reflections about what went well, why, what needs to be improved, and how, and then identifying concrete improvements. Critical debriefing unearths cognitive biases and shows how decisions made sense at the time, reducing hindsight bias. Putting them into a dive log or social media post helps make them more ‘sticky’ for future dives.

Summary

By focusing your diving practice on these decision‑focused tools, you can build the mental discipline needed to recognise stress, challenge assumptions and make safer choices underwater. Your goal is not to eliminate all risk but to understand and manage the human factors that most strongly influence beginner divers’ decisions. Each dive becomes not just an adventure but an opportunity to refine your judgment and strengthen your ability to navigate the underwater world safely.

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver. Along with 12 other instructors, Gareth helps divers and teams improve safety and performance by bringing human factors and just culture into daily practice, so they can be better than yesterday. Through award-winning online and classroom-based learning programmes, we transform how people learn from mistakes, and how they lead, follow and communicate while under pressure. We’ve trained more than 600 people face-to-face and 2500+ online across the globe, and started a movement that encourages curiosity and learning, not judgment and blame.

If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider the first step in developing your knowledge and awareness by signing up for free for the HFiD: Essentials class and see what the topic is about. If you're curious and want to get the weekly newsletter, you can sign up here and select 'Newsletter' from the options

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.