Safe diving starts from the system. Not from the human.

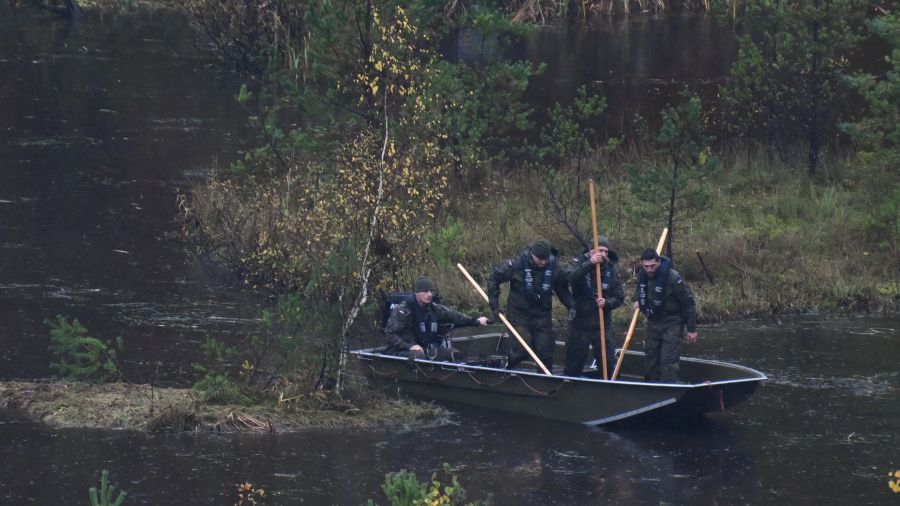

In the autumn of 2023, divers from the Specialist Water Rescue Group of the State Fire Service conducted a complex search operation on a reservoir. At the request of the police, they were searching for the body of a missing person. The case attracted media attention, which put additional pressure on those leading and commissioning the search. During the operation, a tragic accident occurred—a firefighter-diver performing the search alone was killed.

The more complex and formalised an organisation is—in this case, the State Fire Service (PSP)—the more formalised the activities of those performing operational tasks are. The types of tasks performed are precisely described; procedures apply not only to the team but also to the equipment that should be used in given conditions, the procedures that should be followed, and the methodology for carrying out work and ensuring the safety of those performing these tasks. The group of firefighter-divers consists of at least two junior divers, usually teams of 3–6 people as part of the PSP Diving Team. At the site of operations, there should always be a supervisor—a diver-instructor or diving operations manager. Their task is to define the assignment and safety conditions, approve the dive plan and emergency procedures, and maintain and check documentation. A few days after the accident, the person who served as the Diving Operations Manager during the unfortunate incident was no longer in active service with the PSP.

Divers searching the area in Lepusz. (fot. PAP/Adam Warszawa)

In every organisation, sooner or later, mistakes happen. Organisations in which the difference between success and failure—and often between a "good" job and the serious consequences of failure—rests on a single person and their flawless work are weak organisations. Mistakes made in certain cases can lead to high-consequence accidents. Mistakes result from ignorance or non-compliance with procedures, lack of information, faulty or disturbed communication, lack of appropriate regulations, lack of supervision, conflicting or divergent goals, fatigue, inadequate or lack of training, and other factors, as well as errors made by the people performing the tasks. Not all of these mistakes lead to accidents. Often, many of them occur and still do not result in incidents, failures, or accidents. The resilience and safety of an organisation are related to the number of barriers and systems supporting employees in performing their tasks correctly, and to organisational methods of recognising and dealing with mistakes.

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1819735

A cardiac surgeon, after surgery, left a surgical sponge in the patient's heart. A check revealed an incorrect number of used sponges. This was reported the next day, and a decision was made for a second surgery. Shortly after the second procedure, the patient died. The prosecutor charged the surgeon with unintentional endangerment of life or serious bodily harm and unintentional manslaughter.

A nurse on duty in a ward was to take a patient for an examination. The patient was frightened and very anxious. To support the 80-year-old woman, the nurse administered a sedative. Due to a mistake, she gave the wrong medication, which caused cardiac arrest and the patient's death.

Organisational culture can support adherence to procedures and safety measures, or it can create situations where no one feels part of a larger system, and everyone is left alone with problems they must face in their daily work. When no one is interested in problems or in organisational support for solving them, there is a drift away from procedures, rules, and regulations. If tasks cannot be performed according to procedures and no one cares, and only results and completed tasks matter, those responsible must cope as best they can.

Blame Culture—Fear and Stagnation

In blame cultures—those in which the search for the culprit focuses on people directly involved in the incident and their supervisors—making a mistake usually ends with formal proceedings, a reprimand, and often public humiliation. The organisation is protected at all costs, and the blame is placed on the operators, i.e., those who made the mistake.

The firefighters were under pressure from their superiors due to the media nature of the case. There was pressure from the police unit they were cooperating with to act quickly and efficiently. Finding the body would have helped close the investigation. The team did not have the right equipment and did not follow the prescribed procedures. The person performing the task lacked the necessary experience and adequate safety measures. Everyone performed the task "normally," i.e., as such tasks are usually carried out. Team members knew that to complete their assigned tasks within the expected time, they had to make compromises and deal with problems, which led to bypassing and bending procedures and formal requirements. Otherwise, they would have to refuse their superiors' orders and probably would not be able to act at all. Specialist rescue groups lack personnel, equipment, and training in high-performance operational team management (CRM), and procedures are insufficiently implemented, negatively affecting their ability to perform tasks.

The cardiac surgeon performed many operations each day and was frequently on call. He was overworked, under strong pressure from hospital management and patients. Communication within the surgical team was ineffective. The authority gradient meant that team members could not question his actions. Checklists were not used during or immediately after the operation. Delayed reporting by the support team was due to fear of consequences. There was a lack of systematic patient supervision after surgery, which could have revealed potential complications earlier. The medical staff was not adequately trained in human factors, communication, and risk management.

The nurse was working alone on two wards, although there should have been two nurses per ward. She was also training a newly hired junior staff member—during training, she should not have been on duty or caring for patients, but there was no one else available. Both she and her supervisors wanted to introduce the new person to work as quickly as possible. The medication dispensing machine, which would not have dispensed the wrong drug to the wrong patient, had been out of order for months, and all staff were taking the necessary drugs from it, bypassing safety procedures. The correct medication and the one that was administered had similar names and labels, even though their preparation were different.

Consequences

Such organisations are characterised by an atmosphere of fear and the search for scapegoats. No one is interested in the causes; employees hide mistakes and manipulate data. If the organisation rewards managers and supervisors for faultless and accident-free operation, they will be reluctant to disclose such incidents. If the entire department is rewarded for being accident-free, the person who has an accident will not want to be the one who deprives others of privileges. This leads to a decrease in reported incidents. In corporate environments, there are stories of injured people being carried outside the plant gate, retroactively entering vacation time, or reporting injuries after working hours.

The diving community and training organisations meet the definition of a blame culture. Incidents and accidents are stigmatised and judged without trying to understand the broader context. Denial through distancing is common—looking for differences between ourselves and those who made mistakes, to reassure ourselves and others that we would not act that way. To avoid similar decisions, we should rather look for similarities in our own behaviour. Fear of public shaming and online condemnation leads to situations where people do not report symptoms of decompression sickness and do not admit to having had it. There is no talk of separation from a partner, loss of breathing gas, loss of equipment, getting lost, or uncontrolled ascent. Instructors do not share experiences of poor decisions during training dives, lost students, poorly planned gases, or "broken" standards. There is no reflection on the actions taken, so we will not learn where we made mistakes that did not materialize (e.g., a bad emergency plan or evacuation route—if it was not needed, we will not find out it was inadequate) and what we could have done better.

You cannot fix a secret. Therefore, no steps or actions are taken to improve the situation and prevent similar events in the future. When incidents that cannot be ignored occur, "cosmetic" corrective actions are introduced instead of real process improvement. Usually, these are limited to increased controls, additional regulations, and possibly extra training. The atmosphere in such organisations demotivates people, usually the most engaged ones. It leads to a lack of identification with the organisation, a lack of trust in the organisation and superiors, and ultimately to burnout. In institutions with a strong power structure, there is often a "shoot the messenger" effect. If you report a problem, it means "you have no control" or "you spoil the statistics." Such a culture effectively eliminates initiative and reflection.

In many cases of railway or bus accidents, the driver or operator is blamed, even though problems with fatigue, unclear instructions, time pressure, or lack of support were known and previously ignored.

Air Disaster over the Potomac River

In January 2025, a Bombardier CRJ700 passenger plane collided with a UH-60 Black Hawk military helicopter. Sixty-four passengers of the plane and three helicopter crew members died. Recordings from black boxes and control tower conversations show that both crews repeatedly assured that they were aware of their surroundings and the other aircraft's movements. The NTSB, the organisation investigating the disaster, emphasised that despite repeated reports of incidents where similar events were narrowly avoided in the past, no restrictions were introduced for air traffic in this area. Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport in Arlington is one of the busiest airports in the world. Officials working in Washington and VIPs, often using military air transport, repeatedly pressed to maintain helicopter traffic in this area.

Learning Organization

Learning organisations assume that mistakes are not merely the result of human incompetence but the effect of complex systemic interactions. The key element is understanding how the system developed and allowed this to happen, moving beyond a simple root cause analysis, and definitely not the searching for the guilty party. A recent blog from Gareth talked about the reasons for undertaking an 'investigation', highlighting that these reasons are often in conflict with each other.

Civil Aviation and CRM (Crew Resource Management) Programs

In aviation, the approach to errors changed fundamentally after a series of disasters. The aviation industry, if it wanted to convince passengers to fly, had to ensure it was safe. In the case of an incident, blame could be placed on the crew to save the organisation, but that would not save the industry. A deep understanding was needed of why mistakes occur and how to systematically support operators to increase safety. But this required information, which would be lacking if those involved in such events did not share it out of fear of consequences. Factors identified as significantly contributing included poor communication, authority gradient in the cockpit, lack of teamwork, lack of psychological safety, and single-person decision-making. The introduction of Crew Resource Management (CRM) principles allowed a cultural shift—from "the captain is always right" to team co-responsibility and open communication. Incidents and errors are documented, reported anonymously, and analysed systemically. Reporting systems such as ASRS (NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System) are not for punishment or finding blame, but for learning and strengthening safety, and they work.

WHO Checklists and Just Culture

In surgery, the introduction of the WHO checklist significantly reduced the number of errors and complications. The key, however, was not the tool itself, but the cultural change, encouraging staff to speak up openly if they notice something concerning, regardless of hierarchy. The patient's best interest became the overriding goal of the entire team. The introduction of high-performance training and CRM in healthcare contributed to more efficient work and a reduction in incidents and complications. More and more hospitals are implementing Just Culture—a model in which those involved in incidents and those who made mistakes can, without fear of consequences, explain how the error occurred, to understand how to strengthen the system and avoid them in the future.

"The cost of error is education." – Devin Carraway

Technology companies (e.g., Google, Etsy) practice so-called blameless post-mortems after incidents. The goal is to understand what happened, how the system responded, and how it can be strengthened, not to point fingers at "who is to blame."

"Human error is just the beginning of the investigation, not the end." – John Allspaw

Summary

Formalised institutions such as the Fire Service, Emergency Services, Railways, Medicine, etc., must strive to become learning organisations. Blaming individuals to cover up organisational shortcomings and errors leads to repeating the same practices and, consequently, to further accidents.

In diving, we would like as few accidents as possible. Since recreational diving is an industry without formal oversight, it is up to us—divers, instructors, dive centre owners, boat operators, etc.—to create a learning environment. Any form of attack will limit the chances of understanding how accidents happen, which will not allow us to create new, better practices. Situations will repeat, and accidents that could have been prevented will continue to occur.

How to build learning organisations?

Implement Just Culture. You cannot fix a secret. If the organisation does not know about problems and challenges, it cannot fix them.

Ensure psychological safety. Everyone must feel that reporting a problem will not result in reprisals. Leaders should model openness, humility, and admit their own fallibility.

Understand the emergent outcome of events, moving beyond a root cause analysis. It is not enough to say "someone forgot." We must look for deeper causes and conditions: why did they forget? Did the environment contribute? What procedures do we have to counteract this phenomenon? Are they being followed? How can we improve them? How can the organisation support members?

Procedures for confidential reporting and regular post-mortems. Information about incidents must be useful and widely analysed, not end up in a drawer.

Andrzej is a technical diving and closed-circuit rebreather diving instructor. He works as a safety and performance consultant in the diving industry. With a background in psychology specialising in social psychology and safety psychology, his main interests in these fields are related to human performance in extreme environments and building high-performance teams. Andrzej completed postgraduate studies in underwater archaeology and gained experience as a diving safety officer (DSO) responsible for diving safety in scientific projects. Since 2023, he has been an instructor in Human Factors and leads the Polish branch of The Human Factors. You can find more about him at www.podcisnieniem.com.pl.

If you're curious and want to get the weekly newsletter, you can sign up here and select 'Newsletter' from the options