Are there Cobras in diving?

The rational thing about human behaviour is that it is irrational! It is rational at the time to those involved, but it might appear to be irrational after the event by those outside the event, given that we know the outcome and we can easily join the dots.

Humans respond well to positive rewards and will keep repeating what they are doing to get those rewards. However, rewarding behaviours can lead to unintended consequences if we don’t recognise the activity that we are rewarding.

Two examples outside of diving to get you thinking about what rewards and rewarding mechanisms happen within the diving sector.

How do you think you should solve a problem with poisonous snakes in your neighbourhood?

In colonial India, Delhi suffered from many cobras. This was a problem that needed solving, given that cobras can kill people. To cut the number of cobras, the local government decided to give a reward when dead cobras were presented to government officials. This would appear to be a sound solution - encourage the people to solve the problem for you and reward them for doing so. As such, many people took up cobra hunting and this led to the desired outcome – a reducing cobra population.

And that’s where things got interesting!

As the cobra population fell and it became harder to find cobras in the wild, people become inventive and created a solution to their own current problem, not enough cobras to make money from. What did they do? They started to raise cobras in their homes, which they would then kill, present to the officials, and then collect the reward!

Unfortunately, this led to a new problem, local authorities realised that there were very few cobras evident in the city, but they were still paying out a similar amount of money. They realised that people were gaming the system to make money from the reward scheme. City officials did something else which would appear to be rational at the time, they cancelled the bounty. What do you think the people who were raising cobras in their homes did? Yes, they released all of their now-valueless cobras back into the streets.

In the end, Delhi had a bigger cobra problem after the bounty ended than beforehand. The unintended consequence of the cobra eradication plan was an increase in the number of cobras in the streets. This case has become the exemplar of when an attempt to solve a problem ends up exacerbating the very problem that rule-makers intended to fix.

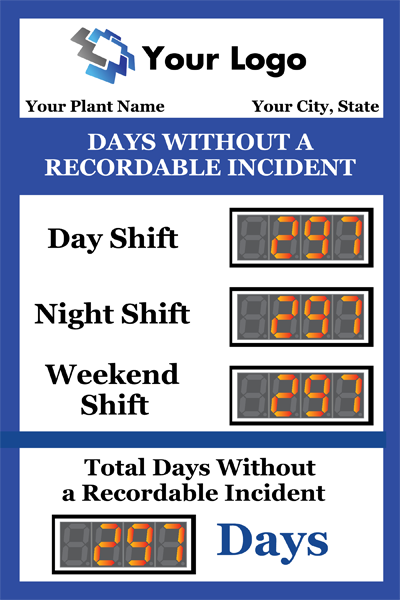

Reporting adverse events while linking financial rewards to low reporting levels

In high-risk industries, contract awards are often influenced by a safety metric called ‘lost time injury frequency rate’ (LTIFR) or lost time injury (LTI) rate. The lower the number (injuries per man hours/days worked), the ‘safer’ the organisation appears to be because they don’t have many/any reportable injuries or incidents. Unfortunately, there is plenty of experience of organisations who do not have a learning-focused culture and where reportable events are not reported. For example, those companies which have displayed something like ‘It is 235 days since we have had a reportable incident, do your part for safety’ are not making it easy to report an incident, especially if the company ties a financial behaviour to maintaining that value. How likely are you to report something if it is going to cost you/your peers a bonus? ‘Irrationally’ this is exactly what was happening on the Deep Water Horizon drilling rig where the pressure to keep ‘traditional’ safety metrics low overrode the concerns associated with drilling the ‘well from hell’ where all sorts of ‘process’ safety issues were missed.

Rewarding one metric (low LTI/LTIFR) can mean that other less tangible, but more important, metrics are not considered in how operations are run.

Another way in which high-risk industries think they can help improve learning is by having safety observation cards submitted on a daily/weekly basis and mandating a minimum number. What happens now is people write anything in those cards to hit the quota, even writing the cards before they go on shift and handing them in at the end. The reporting system is now flooded with rubbish data and the safety teams waste precious time sorting through looking for the needle in the haystack.

What has this to do with diving?

Certifications and awards. What metrics are rewarded in diving? Agencies, with the best intentions, award their instructors, instructor trainers, course directors, and dive centres for high(er) numbers of certifications. These awards are not based on the quality of the instruction delivered, nor on the length of time which students/graduates remain in the diving industry, but rather on how many certifications are issued. There are numerous examples of these metrics being gamed.

Numbers of dives/hours. As part of the progression process through diver training, especially to move into the professional field, you often must have a minimum number of dives. On the surface, this sounds like a good idea. The number of dives can be correlated with experience. However, a dive can be as short as 20 mins and as little as 6m in depth. When these metrics are used, Goodhart’s Law gets invoked – minimum standards become the target standard. By having a single assessment process (instructor candidate trained and assessed by the same trainer and examiner), it can mean that standards will drift because there is no independent check. Some agencies have introduced measures by which the instructor training has to be conducted by multiple trainers and the examination is by another instructor examiner. They have also provided better standards for experience including mixing numbers of courses, the number of certifications and numerous different environments. This increases costs to the consumer but ensures a higher quality instructor.

Reporting adverse events/near misses. Looking at social media, the ability to report near misses is dependent on the culture and attitude of the groups in which the adverse events will be reported. If there is an adversarial culture and individuals are named and shamed without any attempt to understand the context or local rationality (‘how it made sense at the time’), then members of that group are unlikely to share stories inside or outside the group fearful their account will be used as an ’example’, this is even the case if they have really important lessons to be identified/learned. Two open groups on Facebook which facilitate learning are the ‘Scuba Accidents and Risk Management Techniques for Divers’ and the group I run ‘The Human Diver: Human Factors in Diving’ and I’d recommend visiting both. In both cases, social rewards occur when adverse events are discussed, and importantly, conversations can happen which allow the context and local rationality to be explored without adversarial judgement.

What metrics would be useful?

Shared Learning. How about creating a forum within your organisation that focuses on two key areas for learning?

- Learning identified. This is where instructors or organisational members e.g., dive centre staff can make a post highlighting something they learned, the context associated, how they solve the ‘problem’, and how the improvement made a difference. The more context, especially regarding error-producing conditions, the more learning that can happen.

- Needing help. This is where instructors or members of the organisation can ask for help from others in the group with a problem they currently face. You will be surprised by the number of others likely facing the same issue!

In both cases, it requires leaders or senior instructors to lead by example. Many senior instructors are held on a pedestal of excellence and yet they make mistakes and can continue to learn. Their humility will allow others to come forward because a level of psychological safety has been created.

Learning Events. Do you have a 'Wooden weight-belt of the year award' (or similar) which is for the stupidest thing done that year by a club or dive centre member? Consider what a couple of members of the Victoria Sub Aqua Group did after they attended the 10-week webinar series from The Human Diver - they stopped the 'stupid' award and replaced it with a 'learning award' and focused on the most powerful learning event that year.

Summary

Be careful what you reward or punish within a system. If you treat (punish) near misses or deviations from standards without understanding the context, you will end up driving those stories for learning underground, and the next opportunity you have to find out about them is when a serious ‘unhideable’ event occurs. High reliability/high performance organisations look for 'weak signals' to identify where their system is drifting.

Learning is to be celebrated. When divers or instructors deviate from standards or an adverse event occurs, there is an opportunity for the team and organisation to learn. When massive organisations like BMW celebrate failure, you know it isn't necessarily a bad thing!

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a niche company focused on educating and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website.