Human Factors Analysis of a Maltese Diving Fatality

The purpose of any accident or incident investigation should be focused on learning and not blame or punishment as the two are pretty much mutually exclusive: the narratives you use to determine how and why it made sense to do what you did, can also be used as evidence of a breach of standards, protocols or guidelines, even when those breaches occurred because of an ‘error’. The difficulty comes when the judicial system becomes involved because its goal is not learning, but rather to ensure that the laws of the land are upheld, even if these appear to be at odds with what is ‘right’ and learning. Having an independent body who are trained and resourced to undertake learning-focused investigations is something the diving industry lacks. For example, the Danish Maritime Accident Investigation Board (DMAIB) produced a learning-focused report based on a grounding when the Master of the Beau Maiden fell asleep, something that many would consider should be a punishable event.

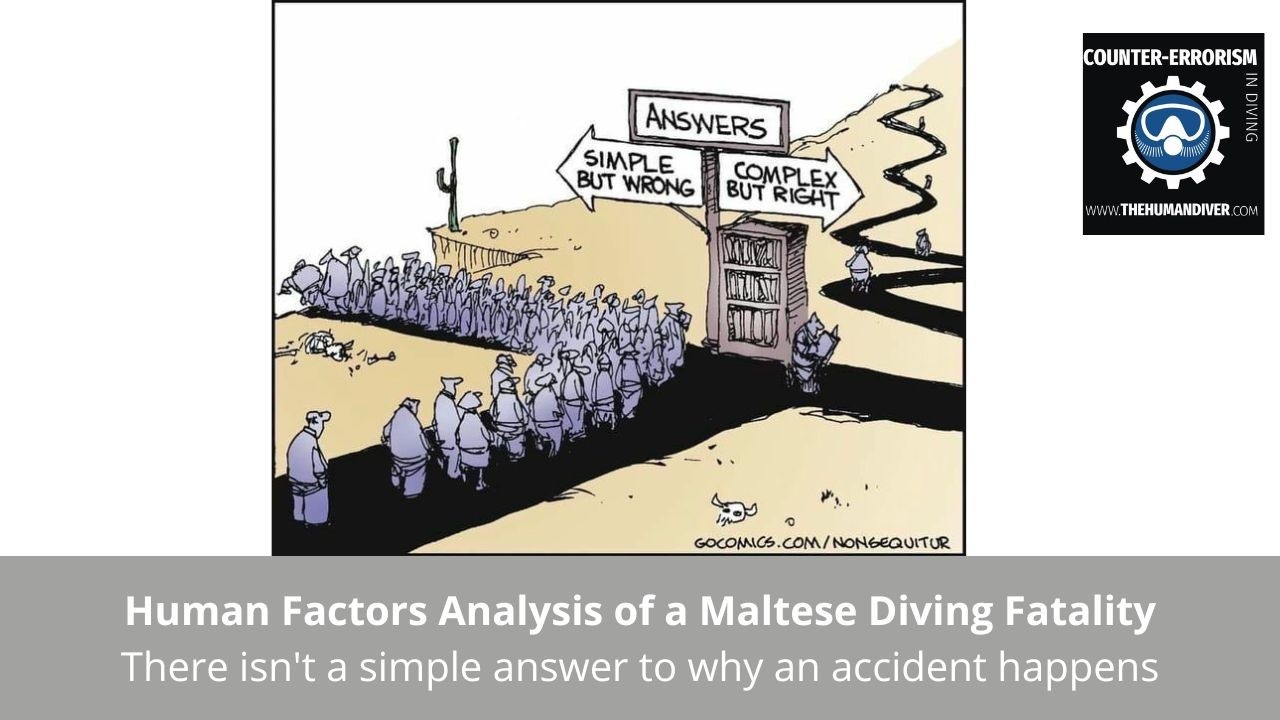

No apology is made for the length of this blog - as the title image shows, if we jump to simple conclusions when it comes to incidents and accidents, we nearly always find them to be wrong when we are in a complex environment, which diving is.

The blog is arranged into ten sections:

- A brief synopsis of the event.

- Human error and violations.

- Understanding our perspectives and how they shape our sensemaking.

- Systems thinking framework

- Government Policy and Budgeting

- Regulatory Bodies and Associations

- Company Management

- Physical Processes and Actor Activities

- Equipment and Surroundings

- Summary

The following links and documents were used for reference and source material:

Judgement Details from Maltese Court (Maltese)

Professional Dive Schools Association of Malta - Facebook Page

Scuba Tech Philippines - Andy Davis

A brief synopsis of the event

Two divers entered the water for a shore dive on Gozo. One was using twin-7 litre (200-300 bar*) cylinders with a 7-litre stage of 50%, and the other diver was using a CCR and had a bailout cylinder. During the dive, two uncontrolled ascents took place by the OC diver, with the OC diver struggling with their buoyancy control, likely due to being underweighted. At some point, the OC diver made a rapid ascent to the surface but was not followed by the CCR diver (they had a decompression overhead). On surfacing, the CCR diver spotted a diver on the beach who they thought was their OC buddy because of how they were dressed. However, after they reached the beach to exit, it transpired it wasn’t their buddy. The OC diver was found dead shortly afterwards. Their main cylinders were empty but their stage still had gas in it.

*court proceedings show different values for cylinder pressures.

Human Error and Violations

Human error is everywhere. We cannot ever get rid of it because it is a by-product of our adaptive behaviour within a world which never has perfect information. Human error, at its most simple, is an unintended outcome (from a preferred behaviour). Violations are a special class of error which historically, were believed to have some level of ‘choice’ involved. However, modern safety research shows that it is easy to create circumstances where individuals will violate the standards or rules because of the context they are in and the goals/rewards they will face. Human error (or a violation) is not a cause of an accident, rather they are the symptom of a weakness somewhere in the system that needs to be explored.

Understanding our perspectives and how they shape our sensemaking

We need to recognise that actions taken by those at the time might appear to be ‘stupid’, ‘reckless’ or ‘irrational’ but human nature has shown time and time again, that we have bounded or local rationality - it makes sense for us to do what we did at the time given our knowledge, our goals, our experience and the drivers that we faced, not just at the ‘sharp end’ but also within the whole system. This is what learning investigations focus on.

In 1988, a passenger train passed a stop signal and crashed into a stationary train, leading to 35 people losing their lives and 484 being injured. The simple ‘cause’ was old wiring hadn’t been removed when the new wiring had been installed and a short had occurred leading to an incorrect signal being displayed, however, the real causes were much more complex. Anthony Hidden QC said in the report into the accident “I have attempted at all times to remind myself of the dangers of using the powerful beam of hindsight to illuminate the situations revealed in the evidence. The power of that beam has its disadvantages…There is almost no human action or decision that cannot be made to look more flawed and less sensible in the misleading light of hindsight. It is essential that the critic should keep himself constantly aware of that fact.” Hindsight allows us to identify, after the fact, the simple (poor/bad) decisions that were missed within the myriad of possibilities that existed at the time. Research shows us that even knowledge of this bias doesn’t protect us from its effects.

Modified from Woods et al, 1998. A Tale of Two Stories. Contrasting Views of Patient Safety

Modified from Woods et al, 1998. A Tale of Two Stories. Contrasting Views of Patient Safety

Hindsight bias is just one of a few biases that can seriously impact our learning from an event. The next one to consider is outcome bias, where we do not consider the quality of the decisions at the time of the action but rather focus on the outcome. In this case, one diver died, but if they had survived with almost the same contributory and causal factors present, would we consider it in the same way? Linked with outcome bias is severity bias, the more severe the outcome, the harsher we judge the event or behaviours. Two examples exist in this case, the loss of life and the sentence given by the judge.

We also need to consider the fundamental attribution bias which leads us to focus on individual performance and behaviours rather than the context in which the individual or individuals were operating. In this case, both divers knew each other, but we don’t know if this lack of control of buoyancy, or having a rapid ascent, was a known issue prior to this fateful event. Accidents and incidents happen as deviations from ‘normal’ behaviour, not from a failure to adhere to rules. ‘Normal’ behaviour in a safety-critical environment is what keeps people safe because they are constantly adapting to the situation at hand, aware of their goals, and their constraints. However, at some point, they lose the capacity to manage safety and an accident happens. An investigation should look at what the difference, the tipping point, was. These are normally ‘conditions’ rather than ‘actions’.

The use of absolutes, e.g., always, never, should be avoided when describing activities or decisions made in a complex environment. For example, ‘Never Events’ are used in healthcare to describe those events which should not happen. However, we need to consider that to prevent never events we need to always have optimal conditions present.

Finally, counterfactuals (should have, could have, would have) do not necessarily help learning because they are retrospective and informed. They tell a story that doesn’t exist, normally where the person involved ‘zigged’ when they should have ‘zagged’, as illustrated by this image from Sidney Dekker.

Dekker, Field Guide to Understanding Human Error

Dekker, Field Guide to Understanding Human Error

Systems Thinking Framework

There are different ways or lenses to look at an event. We can take a legal perspective, we can take a medical perspective, we can take a technical (equipment) perspective, or we can take a human factors or systems thinking perspective. Each of these will give a slightly different understanding, causality and rationale for the event. This blog has been written with a human factors and systems thinking perspective in mind.

This framework from Jens Rasmussen has been used in numerous case studies and research reports, including the outdoor activities sector in Australia, because it looks at the whole system rather than the individual performance of those involved.

Rasmussen, 1987: Risk management in a dynamic society - a modelling problem

Rasmussen, 1987: Risk management in a dynamic society - a modelling problem

The framework on the left looks at what direction and guidance come down the system (arrows on the left), and what feedback goes back up on the right. This vertical framework is then mapped to specific system areas (larger images) where events and actions can be plotted, with their relevant relationships joining them. By looking at the different levels within the system, we can see if there are more issues at hand, rather than just the proximal causes which are so often the focus in diving incident reports. The impact of time, from left to right, can also be used to identify what other factors may have preceded the event in question.

Government Policy and Budgeting

The key law which was being considered in this case is Article 225 of Maltese Law, which states

"Anyone who, with a lack of thought, with carelessness, or with a lack of skill in his art or profession, or with a lack of observance of regulations, causes the death of someone, is liable when found guilty, the penalty of imprisonment for a period not exceeding four years or a fine not exceeding from eleven thousand six hundred and forty-six euros and eighty-seven cents (11,646.87).”

The proceeding also stated that four essential elements of criminal behaviour needed to be present:

(a) voluntary action or omission;

(b) harmful event or occurrence;

(c) causality between the action (or omission) and the harmful event or occurrence; and

(d) the foreseeability and exceptionally the foreseeability of this harmful event or occurrence.

Looking at these in turn. Safety science has shown that while errors of omission (slips, lapse or mistakes) are more forgivable than errors of commission (violations), in all cases, the variability of human performance means that errors are normal, no matter how experienced or knowledgeable the individual is. Criminalising error does not help anyone, especially when it happens in a complex domain.

In terms of an event, (b) is a truism, something needs to happen for there to be a criminal act. At the same time, the failure (variability in performance) and subsequent learning occur in the actions preceding the adverse event, not the event itself. In this case, had everything been almost the same, but the diver had not died, then the same learning opportunity would be present, but there wouldn’t be the judicial interest. Whether those involved would have shared their story to generate community learning is questionable, but that is unlikely down to a lack of Just and Learning Cultures within the diving community.

“Foreseeability” is heavily influenced by hindsight (see the section above). The power of this bias should not be discounted. Research has shown that even when subjects know that they will be subject to hindsight bias, they still fall foul of its effect and think that something would have been easier to spot by those involved than it was.

“The reasonable man”.

The proceedings state

"The amount of prudence or care which the law actually demands is that which is reasonable in the circumstances of the particular case. This obligation to use reasonable care is very commonly expressed by reference to the conduct of a 'reasonable man' or of an 'ordinarily prudent man', meaning thereby a reasonable prudent man: "negligence", it has been said, "is the omitting to do something that a reasonable man would do, or the doing something that a reasonable man would not do" ... What amounts to reasonable care depends entirely on the circumstances of the particular case as known to the person (Carrara, Programma, § 87n.)”

Historical law shows that while there is a ‘fictional character’ - the ‘reasonable man’ - safety science and behavioural economics show there can be no such thing. This is for a number of reasons: individuals behave differently to groups of individuals, individuals behave locally rationally in real-time but in hindsight appear irrational, and behavioural economics shapes risk and reward. The diving community is not representative of the wider population when it comes to perceived and acceptable risks - are they 'prudent'? Therefore, what is ‘reasonable’ considering a proportion of social media responses from instructors/technical divers indicate they would have done the same as the surviving diver? Is the reliance on this premise still valid in such cases?

Evidence to meet the legal threshold.

The following is from the proceedings, translated from Maltese to English "The main evidence that convinces the Court that the defendant actually acted with conduct in which [there are found] elements of the crime contemplated in Article 225(1) of the Cap. 9, is found mainly in the report of the expert Dr Charlie Azzopardi and from the testimony of the same defendant which was given on various occasions during the investigation, the magisterial inquiry as well as during the hearing of this procedure." The statements made by the expert witness will be considered in the different sections below.

Leniency in sentencing.

The court recognised that even though, in their mind, the accused is guilty under Article 225 (1), the deceased actions were also contributory and causal to their death. As such, the surviving diver was given a two-year suspended sentence for four years, which meant that they would not need to spend time in prison as long as nothing untoward happens in the next four years. This application of leniency is similar to the case of the nurse, Rodando Vought, in the US, where multiple systemic failures led to the death of a patient.

Liability outside Malta.

The premise behind Article 225 is not unique to Malta. For example, in the US, something similar is codified in the restatement of torts.

“42. Duty based on Undertaking

An actor who undertakes to render service to another that the actor knows or should know reduce the risk of physical harm to the other has a duty of reasonable care to the other in conducting the undertaking if (a) The failure to exercise such care increases the risk of harm beyond that which existed the undertaking or (b) The person to whom the services are rendered or another relies on the actor’s exercising reasonable care in the undertaking.”

This article from 2002, shows that litigation (not criminal action) has been successful in the past with a buddy pair and highlights a duty of care between buddy/team members when it comes to civil action. It is not clear if there has been any criminal case law in the US relating to this.

It is believed France has a very strict protocol regarding responsibility/accountability for accidents and incidents in sports/adventure sports.

The British Sub-Aqua Club, the National Governing Body in the UK, has their Safe Diving Guide, which covers many more aspects of Safe Diving Practices in an 80-page document. The BSAC also has a page concerning Duty of Care and Welfare. Breach of the SDP document would mean that the individual divers would not be covered by BSAC or disciplinary action might be needed. The British Mountaineering Council (BMC) have produced these open Risk, Responsibility, Duty of Care and Liability Club Guidelines which are only 6 pages and cover key factors the diving community should be aware of.

Regulatory Bodies and Associations

Recreational Buddy Diving.

“The whole scope of the diving buddy system is for the two divers to be close to each other to assist each other in any untoward event during the dive.“ - expert witness. At the recreational level, all agencies teach buddy diving. This is a loose concept of a team where there is mutual support between two (or more) divers in the event of a problem but this mutual support is not the “whole scope of the diving buddy system.” as there are more factors involved including cross-checking, shared tasks, and reduced cognitive loading. At the recreational level, there is no planned decompression or substantial physical overhead (wreck penetration is allowed - to limits), so an ascent to the surface should be possible in the event of an out-of-gas situation. In the event of buddy separation, divers are (normally) taught that they should search for their buddy for one minute at depth, and then ascend at a safe rate, search on the surface and raise the alarm. The problem is that this isn’t what happens in the real world with many examples of divers staying at depth and completing their dives and so there is a difference between what is expected to happen (‘Work as Imagined’) and what really happens (‘Work as Done’). Often there is an assumption made about what will happen in the event of separation but from the author’s experience to be the norm to cover it as part of a dive brief, especially if divers are used to diving together, which was the case for these two.

Technical Diving - Team Diving/Self-Sufficiency.

At the technical diving level, the concept of self-sufficiency and teamwork are brought to the fore. Every diver should be capable of making a solo ascent, completing the decompression as required, and surfacing safely. Notwithstanding this, some agencies strongly promote the value of effective teamwork in trapping errors or problems before they become an issue and helping to mitigate them if and when they do manifest themselves. More effective problem identification and solving processes are needed because the diver cannot immediately surface due to either a physical or decompression overhead.

In this case, the dive was undertaken with a qualified technical diver using a rebreather and a diver using a technical OC configuration (twinset and stage). The twinset was configured as 200- or 300-bar twin 7s (there is conflicting information in the judgement). So while a decompression overhead was possible with a maximum depth of 30m, while still maintaining a useful minimum gas to ascend as a pair (if that was the plan), the decompression obligation would have been minimal. Without knowing the gas consumption rate of the deceased diver, it is not possible to determine a likely decompression obligation (based on their bottom time). The no-decompression limit for 28m on air is approximately 23 mins (if straight down and staying at depth). No profile was provided in the proceedings.

The following statement from the Professional Diving Schools Association (PDSA) made on 24 November on Facebook brings up some interesting points regarding ‘Work as Imagined’ and ‘Work as Done’.

“Technical divers are taught to be 100% self-reliant. They are not taught on the buddy system, but are obliged to plan every dive in detail, try to foresee all eventualities and plan for these without relying on help from anyone else…The type of equipment used and the fact that this was a dive with decompression does suggest this was a technical dive…Ms Gauci and her buddy both held technical diving qualifications. They would have therefore been trained to be 100% self-reliant.”

The use of absolutes e.g., '100%...' & 'every dive' should be considered a red flag when comparing an event or action to reality because there are always exceptions. Just because someone holds a certification, it does not mean that they are competent in their approach - there are plenty of examples of this incident reports and on social media. Conversely, someone can be competent without a certification. In the proceedings, the qualifications of the deceased are not described other than they were going to be completing their MOD 1 CCR course in the coming months and that they didn’t have a drysuit certification. So it isn’t clear what dive training they had outside of the Armed Forces of Malta. While it is not a legal requirement in many locations to hold a drysuit certification to dive (you’d normally need one to rent a drysuit), it is certainly a good idea so that failure modes can be learned and mitigations practised: this includes knowing what to do if an inflator valve is leaking as appears in this case. The proceedings don’t describe the dive profile, so it isn’t clear whether this was a (planned) decompression dive. However, if the CCR diver had 2 mins of decompression to do and they were using a set-point between 0.7 and 1.3, then as the deceased was using 21% as their back gas, it was likely there was a decompression obligation for the deceased. There was nothing in the judgement that described the deceased’s dive profile and what their decompression obligation was.

Company Management

This was a recreational dive between friends and was not under any formal dive centre processes.

Notwithstanding no formal dive centres being involved, the statement “Compressed air for diving purposes must never be supplied by an unlicensed operator with questionable maintenance on compressor.” sits at this level within the framework. There was nothing in the proceedings which provides the evidence surrounding 'questionable maintenance'. It is also not clear why running a compressor needs a licence as there are numerous divers who do this and there is nothing in these Maltese Diving Regulations. (Edit: it appears portable compressors are exempt, but a fixed compressor needs planning permission. Details coming shortly).

Technical and Operational Management

This section looks at those activities or events which are set above the specific dive operation e.g., planning, currency and in-water skills development.

Currency and Competency.

Currencies and competencies in the sport diving domain are somewhat lax compared to other high-risk areas. For the vast majority of divers, once you have qualified as an instructor or diver, you do not need to practically requalify your diving skills with an instructor or instructor trainer, so you could have been certified 20 years ago, and there isn’t a need to formally update your skills or be practically re-evaluated. This means that a diver could be “Rescue Diver” certified, but they have never practised those skills again after the class. I have had MOD 3 (100m) CCR divers on my HF courses who only do live bailout ascents from depth when their cylinders need to be retested, this could be once every 2.5 years. Lack of representative training between courses is not uncommon, with the cost of refilling gas, risk perception, and outcome bias (bad things don’t happen) being drivers.

Rapid Ascents/Loss of Control of Buoyancy.

In 2016-2017, I created a survey to examine the different types of diving incidents and their causes as this data was missing from the literature. More than 1000 divers responded and of those, 23% had had an unplanned separation and a solo ascent. It should also be noted that 8% had had an uncontrolled buoyant ascent and 6% had totally run out of gas on a dive. Therefore, to have a rapid ascent, and be solo too, is not uncommon in the sports diving sector. However, there is a considerable stigma associated with reporting adverse events like this, and therefore the true scale of the problem is unknown but given the experience in other areas, reported events are likely to be in the order of 10-20% of actual events. “This case exemplifies a diving fatality where multiple contributing variables ended up summating to one unfortunate, but predictable outcome.” - expert witness. Predictability is easy after an event, but in real-time, this isn’t the case. As stated above, rapid ascents, separations, and equipment issues don’t always lead to fatalities, even when combined. This is hindsight and outcome bias at play.

This statement "Fatigue, unfamiliar equipment and compressed air for diving purposes provided by an unlicensed third party, and drysuit use without prior training in its function resulted in buoyancy issues during the dive, together with overuse of a finite gas supply during the dive." It is not possible to see how providing compressed air by an unlicensed third party" causes buoyancy issues. Furthermore, every dive has a finite gas supply, so this is a truism for all dives, not just this one.

Gas Planning.

There is nothing in the proceedings about the gas planning protocols or processes used. Having mismatched equipment (CCR and OC) is not unusual, but care needs to be taken to ensure that all members of the team are aware of the limiting factors to end the dive (thermal considerations, maximum bottom time, maximum decompression time, or minimum gas. Without some form of logging system, it isn’t known why the diver ran out of gas. It could have been higher breathing rates, or the multiple ascents and descents and having their drysuit being fed from the small twinset.

Fatigue Management.

The proceedings describe the deceased as having completed a 24-hr shift at the Army base on Malta before catching the ferry to go diving on Gozo. This could lead to a view that fatigue is an issue. “Asked if during this time, the soldiers have time to rest, the Captain replied that unless there is an operation to be done they will be in their barracks and they will rest. He explained that in the shift that Christine was in before she was involved in the accident there was no operation. According to the records, she left the barracks at half past eight in the morning and returned at half past three in the afternoon. From that time she, therefore, rested in the barracks and remained in the barracks until she left the next day shortly before the end of her shift.” Therefore, the issue of fatigue is likely a red herring as the expert witnesses don’t appear to have considered that the deceased rested overnight. There are two statements from an expert witness which would be hard to evidence “fatigue caused buoyancy issues” and “fatigue caused overuse of gas”.

Physical Processes and Actor Activities

The following section will look at those processes and activities which took place on the dive. These have been taken from the proceedings.

Mixed team protocols.

Running mixed teams of OC and CCR is possible but there are many additional factors that need to be considered: bailout, operation of equipment, rescue considerations, dumping gas during the ascent, noticing signs of failure on the CCR etc. Buddy/team diving responsibilities go both ways, could the deceased have rescued the surviving diver if something had gone wrong with their equipment? The CCR diver had bailout but they might not have been able to access it.

Tracking of gas CCR vs OC.

During the proceedings, one of the expert witnesses makes mention of the lack of checking of gas of the deceased diver by the surviving diver. The majority of divers who have technical training won’t check the gas pressures of other divers because a turn pressure or minimum gas has been briefed prior to the dive and there is an expectation that gas will be monitored (this should also happen on a recreational dive too). During a recreational dive, I wouldn’t expect divers to be asking to check gas unless they were new divers and there was a concern that one diver or another wouldn’t be monitoring their gas. Therefore to criticise the surviving diver for not checking the deceased diver’s gas on a regular basis is not necessarily a valid point to make. However, if there was a genuine concern that the deceased diver was unable to monitor their gas when needed, we have to consider that they would have taken measures to address this.

Task-fixation/destructive goal pursuit.

The proceedings described multiple opportunities for the deceased diver to not enter the water (on the ferry and at the dive site), or to end the dive when the surviving diver suggested doing so following the loss of buoyancy control and line entanglement. Such focus could indicate that the deceased diver wanted to complete this dive (for whatever reason). Destructive goal pursuit means completing the activity takes priority over risk management. The deaths of eight climbers on Everest in 1996 is a classic example of this, as is the death of Guy Garman (Doc Deep) in 2015 in Saint Croix. In hindsight, decisions appear to be irrational, but those involved in the activity can easily rationalise their actions and discount others’ suggestions to end the activity.

Violating Decompression Obligation on Final Ascent.

The proceedings state that one reason the surviving diver didn’t immediately ascend to the surface was that they had a decompression obligation of 2 mins at 5 metres. This reticence to ascend was rejected by one of the expert witness saying that it wasn’t a genuine decompression overhead and could have been breached. “He cites having a deco obligation and being light, hence the reason for not following her. This is disproven by his decompression computer”. It is not clear how a dive computer can know the diver is light, although a decompression overhead was present. The decision to omit decompression is a personal decision and there is no official guidance provided as to how much can be omitted because it would open every agency up for litigation. Divers are taught to make this decision themselves inline with first aid training - don’t create two victims when dealing with a hazardous situation. An instructor in the UK recently faced a similar decision to ascend to the surface and breach their decompression obligation or delay their ascent following a medical emergency with their ‘student’. They stayed down.

Not using their buddy for ‘bailout’ when low on gas.

Cognitive loading means that simple decisions are difficult to bring to the fore when in the middle of another task. If the diver or buddy has not practised gas sharing in high-stress situations i.e. no-notice, emergency-type training, then it is much harder to think about executing this skill in real-time when the pressure is on. Stress shrinks the perspective we have, often to a fine spotlight, so that only apparently important details are noticed and the rest ‘dismissed’. This has been described as a ‘loss of situation awareness’ but there is much more to it than that as this blog describes.

Fatigue from having buoyancy control issues.

One of the expert witnesses said that the deceased diver would have been fatigued because of their poor buoyancy control (on top of lack of sleep). It is not clear how this assertion is made regarding physical fatigue unless the deceased diver was spending considerable time trying to constantly swim downwards. The ‘fatigue’ from their working shift the night before has already been covered above.

Venturi adjustment on the 2nd stage.

An expert witness stated that the Venturi controller was open and this could have led to excessive gas being breathed or contributed to the empty cylinders. It is unlikely that the diver would have adjusted their regulator to deal with a low volume of gas during a potential emergency, and not used the regulator on their stage cylinder, a cylinder which had plenty of gas. Using the stage regulator would have had a greater impact on their survivability.

Observation of a diver on the beach.

“The assumption that Ms. Gauci was safe on the surface and swimming back to shore, when no such contact and reasoning was made between the two divers, proved to be highly significant as it ensured the omission of a rescue attempt.” - expert witness. After the surviving diver ascended to the surface, they looked for their partner but couldn’t see them in the water. They saw a diver dressed in a black drysuit which they assumed was the deceased diver. It is not clear the distances involved and therefore the visual cues which would have been available. However, confirmation bias and the framing effect are both very powerful biases, which means that we believe what we see. This effect was a major contributory factor in the shooting down of two US Army Blackhawk helicopters in Northern Iraq by USAF F-15 fighters when they mistook the Blackhawks for Iraqi military attack helicopters (Mi-28 Hinds). Specifically addressing the expert witness statement ”proved to be highly significant” part suggests that the deceased would have been saved if only the accused had acted otherwise, the evidence for which cannot be seen in the proceedings. Furthermore, “ensured the omission of the rescue attempt” is subject to hindsight bias.

“Inevitability of the final outcome.”

There are a number of points to come from the following statement from one of the expert witnesses “the provision of air and unfamiliar equipment, followed by a negligent omission of a rescue attempt and assumption of safety when no assumption could or should have been made, made the final outcome inevitable.“. This statement is heavily biased by hindsight. Assumptions are normal human behaviour, and they allow us to operate in the world in the manner we do. Ironically, despite dismissing assumptions, the witness makes an assumption that this outcome would be inevitable, despite the fact that most solo, unplanned ascents do not end up in a fatality.

Equipment and Surroundings

Drysuit size:

The court proceedings state that the drysuit for the deceased was too large. This causes problems because of the excess air that needs to be managed during the ascent. At 30m, a litre of excessive gas expands to 4 litres on the surface, and not having enough weight to start with is not going to help this situation. It is a good indication that weighting will be a problem if the diver is struggling to descend at the start of the dive. Twin 7s at 200 bar contain 3.6kg of gas, Twin 7s at 300 bar contain 5.4kg of gas. It is not clear how light the diver was, but the 2kg did not appear to make much difference at the end of the dive.

Drysuit inflator.

The proceedings stated that the drysuit valve was not working properly but it did not say what the issue was; it could have been a slow leak into the suit. If this was the case, then combined with a larger suit volume (and associated extra gas), and being underweighted, would have made ascents much more difficult. A slow injection of gas into a drysuit is hard to detect, especially if the suit is too large, or the suit is not ‘run dry’ so it is tight to the body/undersuit.

Summary

This was a tragic accident which was caused by multiple contributory factors coming together at just the ‘right’ point in time and space - these relationships were not linear in nature, but rather emergent. This emergent nature means it is nearly impossible to predict, at the time, what will happen with 100% certainty.

However, using the powerful lens of hindsight, we can clearly see what factors can be made to line up so that “the diver was faced with the perfect storm of a number of physical and technical problems.”. Consequently, it appears that the diver didn’t have the cognitive or physical capacity to resolve, although a medical issue was not ruled out during the court case. To state that this event was inevitable discounts safety science which provides multiple examples of the variability of human performance and why this wasn’t inevitable, and to place the final ‘blame’ on the surviving diver for making an assumption that the diver on the shore was their buddy which led to them not initiating a rescue, misses the point of this research.

This ruling likely has wide-ranging implications regarding the buddy system. In the US, breaches of the buddy system have been subject to litigation, but it is believed that this is the first time a ‘failure’ of the buddy system has been subject to criminal law. Diving is already struggling in this age of litigation, and the criminalisation of human error will not improve matters.

Errors and omissions: This blog was put together over multiple days after reviewing multiple pieces of information from different sources in different languages! There could be errors or omissions. If I have got something wrong, rather than post something to that effect on social media trying to discredit the whole article, please get in touch via the contact form above and I will endeavour to resolve it. I am human too!

AcciMap of this event: The goal was to produce a graphical AcciMap for this event but the research and editing took much longer than planned. It will be put together shortly and added to this page for reference.

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a niche company focused on educating and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website