Top Tips for Diving Instructors: Decision Making.

Oct 01, 2025The following accounts were taken from social media posts following a fatality in poor visibility in an inland dive site. The comments have been modified slightly. As this blog is focused more on decision-making for instructors, it will focus on the bigger, but often invisible, decisions that take place in the instructional setting.

“An instructor had a class of 8 students, and the shop used a DM candidate as an assistant. They were operating in crystal clear water. The instructor arranged students in a circle to perform skills. One of the students had a problem, and the instructor took the student to the surface, leaving the students with the DMC. Then another student had a problem, and the DMC attended to it, finishing just as the instructor returned. They returned to their positions, learning then that another student had died and was lying in the sand with the regulator out.

The fact that leaving the students with a DMC was a standards violation is not the point. The point is that no one noticed a student having a problem and dying while they were in close proximity in crystal clear water.

I have undertaken many OW training dives in low visibility conditions in North America. I never had an incident. However, I have realised after a while that it was not because I was good at my job. Rather, a fair chunk was down to luck. SCUBA is statistically safe, so whatever causes a diver to have a safety incident is very rare, but it can happen. When it happens in poor visibility, no one will know until it is too late.

The classes I led, the classes offered in poor visibility around the entire world, are inherently unsafe. The difference between a dive shop with a stellar record and a dive shop with a higher failure rate may be just a matter of luck.”

“I'm not an instructor although I helped one with classes a few times. I just can't see how teaching basic scuba in low vis is a good idea. Talk about complicating factors. Someone should have had the wisdom to call the dive before anyone got wet. I'd hate to be the adult that made the choices that day.”

The Theory...

The decisions we make now have their seeds sown long before the event occurs. At its most simple, a decision is made by making sense of the situation around us, matching this against previous experiences, expected and rewarded goals, resource constraints (time, money, people…), applying biases and heuristics, and determining the best option to apply. Most of the time, this process happens without us thinking about it.

We are applying ‘System 1’ thinking or ‘Recognition Primed Decision-Making’. We could think of this process as ‘satisficing’, making do, or making educated/influenced gambles.

This process of ‘assumption>decision>feedback>assumption>decision…’ is why we are able to operate at the pace we do in the world we live in. However, there are times and places when we need to engage ‘System 2’ (our slow, logical and methodical brain) to maximise capacity (safety) and minimise errors and the harm they can bring. The following scenarios highlight when we should move from fast thinking to a more deliberate approach:

- When we are in a novel situation, we tend to pick the closest match to what we’ve previously experienced, and the error rate can be between 1:2 and 1:10. Not great odds to have when you’re underwater with students. This could be the first time you’ve had to take a diver to the surface and leave a DMC below with the students. Do they know what to do? How will they make their decisions? How often has a second or third thing gone wrong when dealing with a primary event?

- When we are in a situation that is rushed, critical, difficult or dangerous, the real- or perceived-time pressures can lead us to operate in a fast-thinking mode and miss the bigger picture because we are focused on the ‘nearest crocodile to the canoe’. For example, the course you are teaching backs into another one, and the client is going on holiday next weekend, so they can’t reschedule. There is no flexibility or capacity to extend, and you want to provide a quality service (and gain a positive reputation) for the dive centre.

- When we are conducting tasks that are habitual but still contain serious risks because the ability to control the situation is limited or if a critical step is missed we could end up with a fatal outcome. Examples include more students than you can effectively monitor and control (like the scenario above), or the outcome is catastrophic like an incorrect gas switch on decompression or incomplete/incorrect gas analysis on the surface.

- When we are prioritising competing risks like ‘business risk’ and ‘safety risk’ or the potential losses vs the potential rewards on a dive. Business risks are those risks that impact the viability of the business e.g., cashflow, reputation, costs for maintenance, liability insurance, currency for our own diving, or paying employees/staff. Safety risk management happens when we balance the losses from the irreducible hazards we face while underwater like an injury or fatality, against the rewards we gain by teaching others, having students graduate from a class, seeing and exploring the underwater world, and the payment for teaching.

While we’d like to think that divers and instructors sit down and think about the pros and cons of each decision we’re about to make, in reality, what we do is we make a quick judgment based on past experiences, the social and cultural norms of where we’re diving, and the stories we’ve heard about successes and failures. Most of the time, the outcomes are successful, and we chalk that up as a successful dive, even if we look back it and think ‘That was a bit of a train wreck, I’ll not do that again’.

The problem is that without digging into how we made the decisions we did through a reflective and critical debrief, what we do is take the successful outcome, wrap that around the dive thereby hiding the messy details. By not reflecting on the decisions we made i.e., inside the wrapper, we don’t add to the schema or mental models we will use to make future decisions. This can lead us to normalising the risk we tolerate on subsequent dives; we believe that because nothing happened before, it must be okay to do what we did. The normalisation of deviance is where we socially accept this drift from expected standards and norms, not just the adaptations and variations that take place.

What can we do about this?

As with all of the ‘top tips’ blogs, we’ll give you some tools and ideas on how to improve… in this case, how to improve decision-making for instructors.

- Luck vs Skill. In the first case study, the author recognises that luck does play a part in what we do, and while this isn’t necessarily a bad thing, don’t confuse luck with skills. Ask yourself, if you were lucky or good. If you think your instructional skills and behaviours were good, then you should be able answer the questions, “What did we do well? Why did it go well?” as they applied to that dive. By reflecting on the positive (the ‘saves’) we can replicate those behaviours/actions on future dives or build them into our ‘what ifs’ during dive briefs. Good ‘saves’ without reflection might appear heroic, but they can hide weaknesses in technical, non-technical skills, procedural design/execution and equipment design/manufacture.

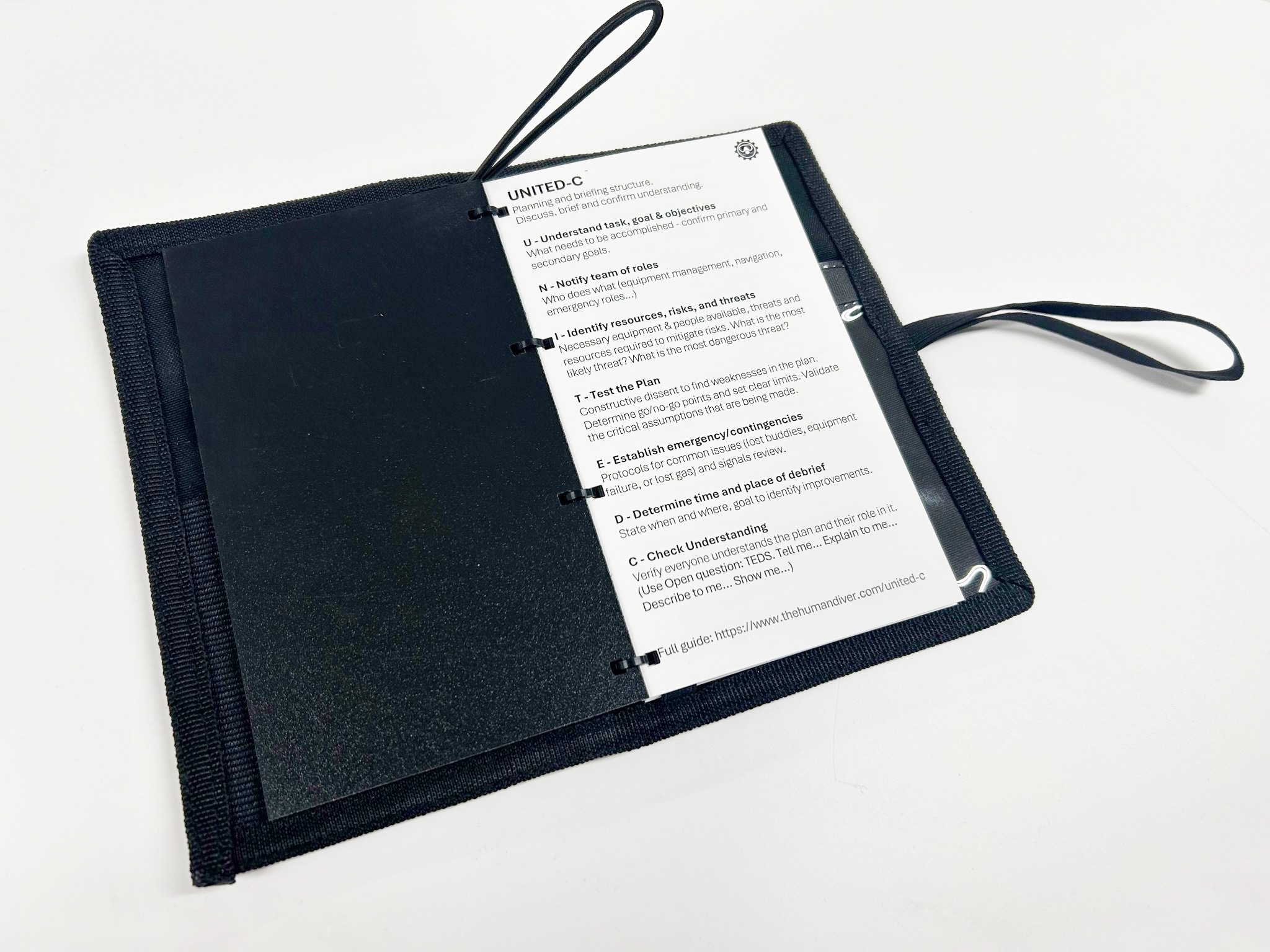

- Challenge the assumptions we make. Most people have a bias for optimism. We think it won’t happen to us (otherwise we wouldn’t do it!). That doesn’t mean we are paranoid when we consider “What if this happens? How will we detect, correct, and recover the situation?” This is what the ‘T-test the plan’ in the UNITED-C is about. Have we validated the assumptions we are making? In the first scenario, we don’t think that 3 major failures (2 dealt with, one ‘missed’ that led to a fatality) would occur, but these ‘thought experiments’ are useful to run at a dive centre or team level to explore controls, contingencies and mitigations. It is much easier to solve a problem in the moment if you’ve already thought about it prior to the dive.

- Separate the quality of the decision from the outcome. It is easy to get sucked into judging poor decisions after an adverse event has occurred because of four very powerful biases:

- Hindsight bias (knew it all along)

- Outcome and severity bias (the more severe the outcome, the harsher we judge it)

- Fundamental attribution bias (focusing on individual attributes, rather than looking at the situation or context).

You can find more about these biases in the many blogs we have. To suspend this judgement, ask yourself, ‘How did it make sense for THEM to do what THEY did?’ not ‘How would I have done this differently?’ From the second scenario above, “I'd hate to be the adult that made the choices that day.” is biased towards outcomes and severity. If nothing bad had happened, would the feelings still be the same?

Image from: Learning in the Heat of the Moment: An Interview With Sabrina Cohen-Hatton

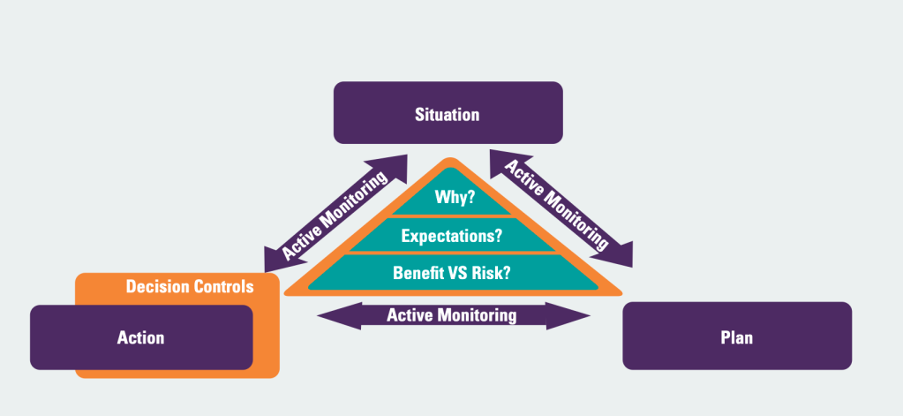

- Put an operational pause in place. The purpose of this pause is to intentionally move us from the fast thinking of ‘System 1’ or RPDM into the slower ‘System 2’ logical thought processes. We can’t help jumping to conclusions, but before you commit and take the action, ask the following three quick questions:

- “Why am I doing this?”

- “What do I expect to happen next?”

- “Is the benefit proportional to the risk?”

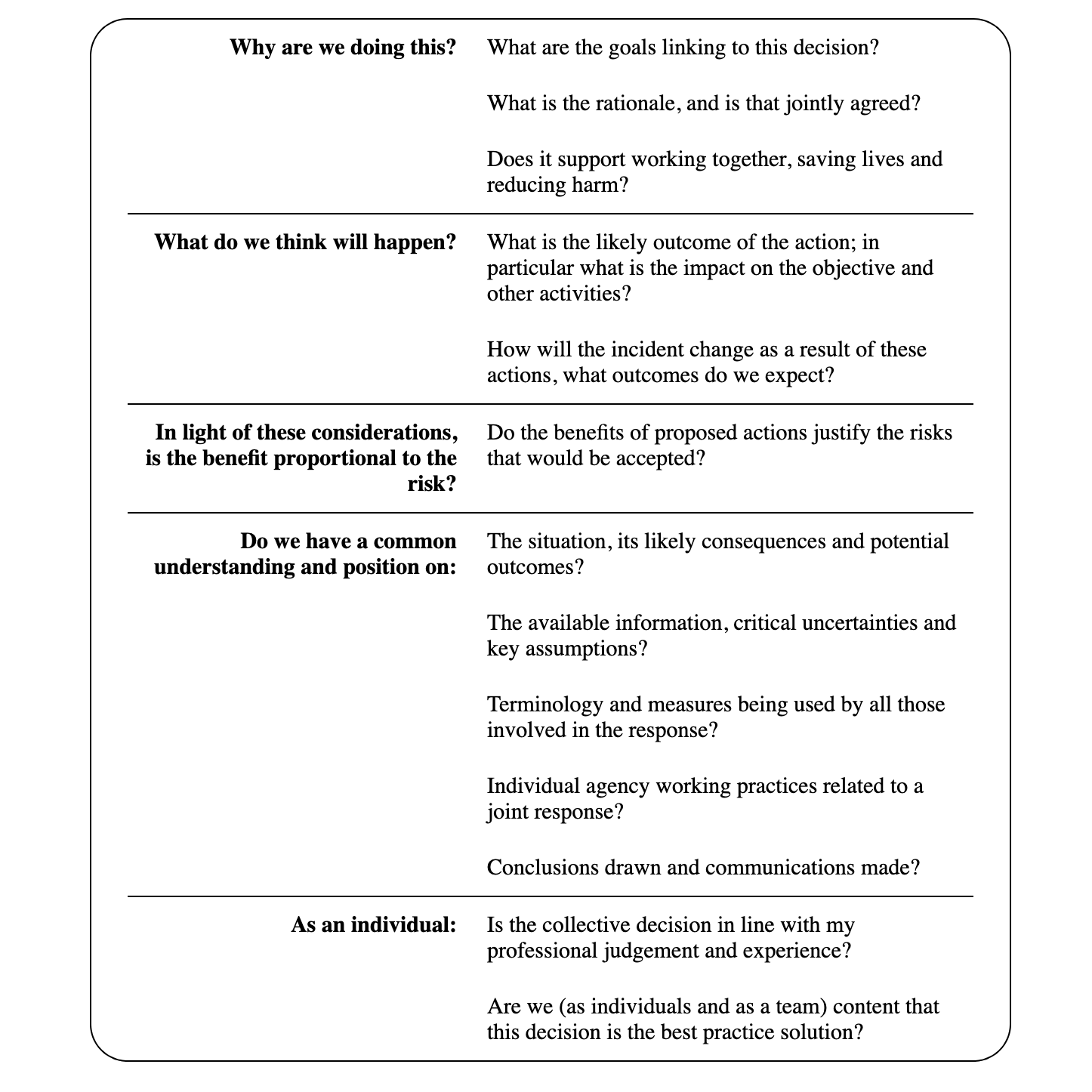

These questions are based on a tool that UK Firefighters use as part of their operational decision-making process developed by Dr Sabrina Cohen-Hatton. In her book, Heat of the Moment, she describes more about what these questions mean – outlined in the table below. This is obviously focused on firefighting, but the concepts are applicable to when you’re in a teaching scenario too.

Image from: The Heat of the Moment. Dr. Sabrina Cohen-Hatton.

Without direct experience or reflective behaviours when reading/hearing context-rich stories from near-misses, it is much harder to determine what is likely to happen next. This is why the sharing of stories is so important, and the presence of psychological safety/Just Culture to allow these to be told. See ‘Storytelling to learn’ for more on the barriers and enablers to this.

Conclusion

We make decisions all the time, and most of the time, the outcomes are what we expect. Consequently, we don’t reflect on how and why the outcomes happened in the way they did, along with the context that shaped our decision, i.e., the performance influencing factors. This means we miss important information on how to make more effective decisions, especially when we are dealing with limited information or when time-pressured. Tools like the operational pause or the validation of assumptions can help us reduce errors by intentionally slowing us down. If you know you’ve got lots of similar tasks during a training day or week, you could even put an operational pause in during the day after you’ve done one serial in a sequence to see if the execution is matching the plan – a mini debrief, if you will. This way, you can see what adaptations are happening in real time and adjust accordingly. The more we reflect on how and why we make the decisions we do, the better our future decision-making becomes.

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver. Along with 12 other instructors, Gareth helps divers and teams improve safety and performance by bringing human factors and just culture into daily practice, so they can be better than yesterday. Through award-winning online and classroom-based learning programmes, we transform how people learn from mistakes, and how they lead, follow and communicate while under pressure. We’ve trained more than 600 people face-to-face and 2500+ online across the globe, and started a movement that encourages curiosity and learning, not judgment and blame.

If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider the first step in developing your knowledge and awareness by signing up for free for the HFiD: Essentials class and see what the topic is about. If you're curious and want to get the weekly newsletter, you can sign up here and select 'Newsletter' from the options.

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.