“The standard you walk past is the standard you accept”

Jun 18, 2018A few days ago a post was made on Facebook outlining the process by which a PADI student or professional could raise a QA claim against a professional or facility. One of the comments written below was 'Snitch!' This frustrated me because my perception based on 26 years in the RAF is that if standards are not being adhered to, then something needs to be said to bring those involved back up to what is expected. The reason is that the standards are there for the safety and performance of all involved. Of course, deviations occurred while I was serving, we made mistakes and undertook at-risk behaviours - we were human after all! Most of the time they were debriefed to find out not just why they happened, but also because innovation can only exist when deviation happens and if that deviation has led to an innovation, then let's learn from it and make what we have better. Feedback worked because, fundamentally, it was normal and expected. Aircrew were used to giving and receiving feedback and did not take it personally nor did they make it personal when providing feedback. This is something that is lacking in the diving industry.

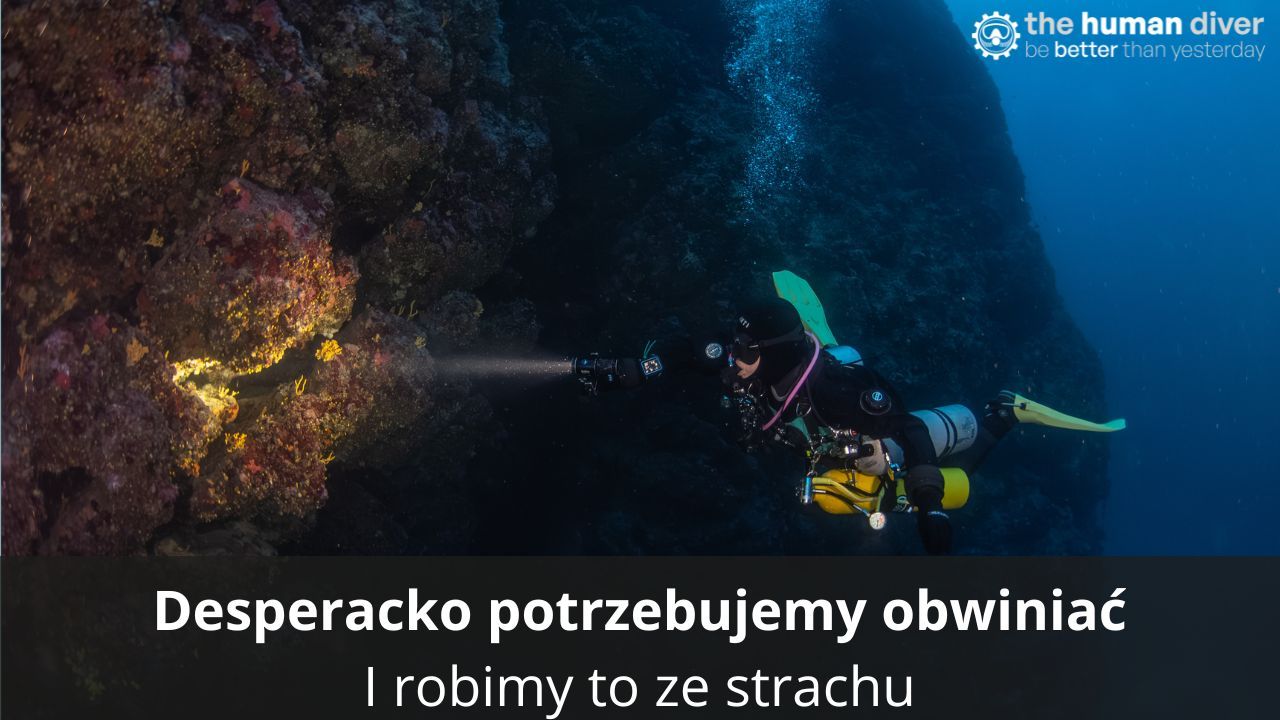

Research has shown that the effectiveness of any developmental process is directly related to the quality of the feedback within the system. Therefore, one of the major challenges faced by the diving community is how to stop performance drift and normalisation of deviance when there are feedback mechanisms with limited effectiveness present. This effectiveness is limited when complaints are often seen to be about blaming individuals for poor performance rather than learning about potential systemic failures. Feedback should be seen as an opportunity for improvement rather than something which opens up professionals and organisations to potential litigation in the future. If instructors are only used to being involved in a feedback or QC process when a complaint is raised, and the reason for the contact from the agency to instructor is to build a ‘case’ to counter any litigation, then we shouldn’t be surprised that feedback is not well received and those involved get defensive.

But deviation is normal. It is the reason I wrote this blog. But that doesn’t mean it should be acceptable. The head of the Australian Army summed it up nicely with this quote, “The standard you walk by is the standard you accept.” If you see something, but don’t say anything, you have condoned the action. If someone provides you feedback on something they have seen, dismissing it without truly listening to the issues presented means you are also condoning the action. If this happens consistently, it is willful blindness.

Not speaking up doesn’t just apply to students providing feedback to the agency about their instructors or other professionals, but also instructors about ITs and IEs who are not following standards for the instructor development process. Certifying instructors without them meeting standards (even as a cross-over) has massive implications for diluting standards and reducing safety across the industry. Recently I was speaking to a US-based instructor whose technical instructor cross-over course was a complete paperwork exercise with multiple violations present. Given recent social media posts about the quality of instructors and ITs, they have decided that it is time to make a stand and QA their IT for breach of standards. They recognise that this opens them up to being removed from teaching status but they have had enough.

The fear of losing their certification card if an instructor is negatively QA’d is a threat used by some unscrupulous instructors to ensure that standards breaches are not found out about. If an instructor falls below the standards expected of them by their agency, and the student didn’t meet the standards, the agency should provide some means to amend the situation that so the student is not disadvantaged. If the organisation doesn’t have such a process in place, then there is limited incentive to report instructors for poor standards.

Finally, part of the problem isn’t just that the students or instructors aren’t raising QA forms to the agencies, it is that the agencies/organisations are not providing a feedback loop to the reporter to show it was worth the effort reporting and that something will be done. Even if that ‘something’ is something as simple as “Thank you for sending this information in. I am sorry, but that doesn’t provide sufficient evidence that we can use but we will keep a record of this to ensure that there isn’t a trend developing.” and then actually do something with that information.

If those who provide QA information don’t get an acknowledgement of some sort, the value of reporting is diminished and reports will stop coming in, this is the same for any reporting system, irrespective of domain. There must be value perceived by the reporter for taking the time to put something in writing. Indeed, the social media posts are full of reports in which divers & instructors have reported practices to agencies but their reports haven’t even been acknowledged. “So why bother?” is a pretty valid question.

The diving industry, considering the risks involved, is in a lucky position to be self-regulating. That self-regulation is predicated on having some form of QA and feedback process to maximise safety while still remaining commercially viable. However, given that there isn’t much between a scary dive and a fatality, then the community needs to be more proactive when it comes to reporting sub-standard procedures and agencies need to listen and provide feedback to their reporters about what is being done. Relying on fatality metrics as a way of determining safety has been proven to be of limited value in other domains when it comes to low likelihood/high consequence risks and if punishment is the normal response, then issues are driven underground. If you want to see how reporting can improve safety and performance, and reduce litigation, you only have to look at this case study in healthcare in the US to see how improvements can happen.

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a niche company focused on educating and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website.

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.