The Importance of Experience: Expertise is different to Experience

Feb 20, 2022It might seem to be obvious that the more experience we have, the more accurate the outcomes of our decision. People also say to get better you should practice more, even more specifically they say ‘Perfect practice makes perfect’. The problem is that perfect practice and experience aren’t the same things. Perfect practice (Eriksson's 10 000 hour rule) gives you expertise whereas general practice in a wide range of environments, with a wide range of people, over a long period of time gives you experience and it is this experience that helps you make better decisions in uncertain situations.

Decision making is informed by situation awareness: sensing data, creating an understanding of what is going on around us now and then projecting into the future what is likely to happen, and finally, executing on that to achieve goals or objectives.

Situation awareness is informed by sensory input, expectations, experience, training and abilities but it is limited. We are constantly filtering data, billions of bits of data, ditching the majority of it. We only pay active attention to those things that we perceive to be important and/or relevant. Something that could be summarised as DIPI. Dangerous. Important. Pleasurable. Interesting. Think about the dog in UP - ‘squirrel’.

Given that we have this limitation, we should consider four critical questions if we want to understand the process of developing experience.

- How do we know what to pay attention to?

- How do we know how much attention to pay to that task?

- How do we really make decisions in uncertain situations?

- How do we know we made the right decision?

How do we know what to pay attention to?

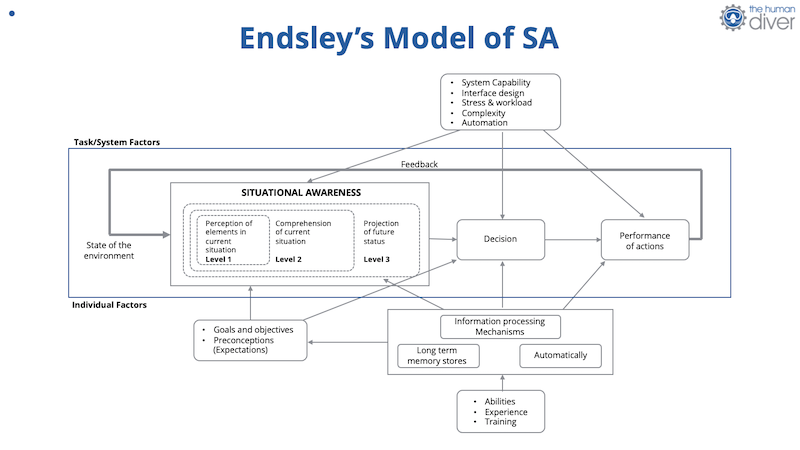

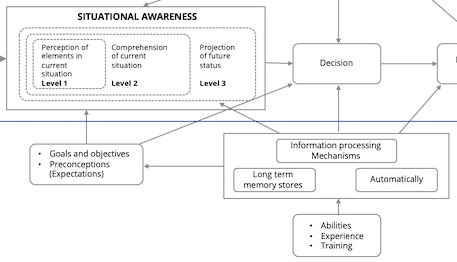

This model of situational awareness was developed by Dr. Mica Endsley, a researcher in the US to help design systems so that it was easier to pay the right amount of attention to certain tasks. In the centre of the model, we can see the key parts of situation awareness; sense/perceive information, process it to make sense, project into the future about what might happen. This 'information gather' process is the first part of the decision making cycle (Gather Information >> Determine Options >> Decide Option).

At the bottom of the model we can see what influences what we pay attention to and a number of these relate to experience. Over time, we start to develop an idea of what is important to pay attention to based on our training, our real-world experiences, what we have read, what we have heard or watched. All these go into the long-term memory store which we reference when we sense information. The more experiences we have, the greater the likelihood that the situation we are facing now is in our long-term memories.

How do we know how much attention to pay to the task?

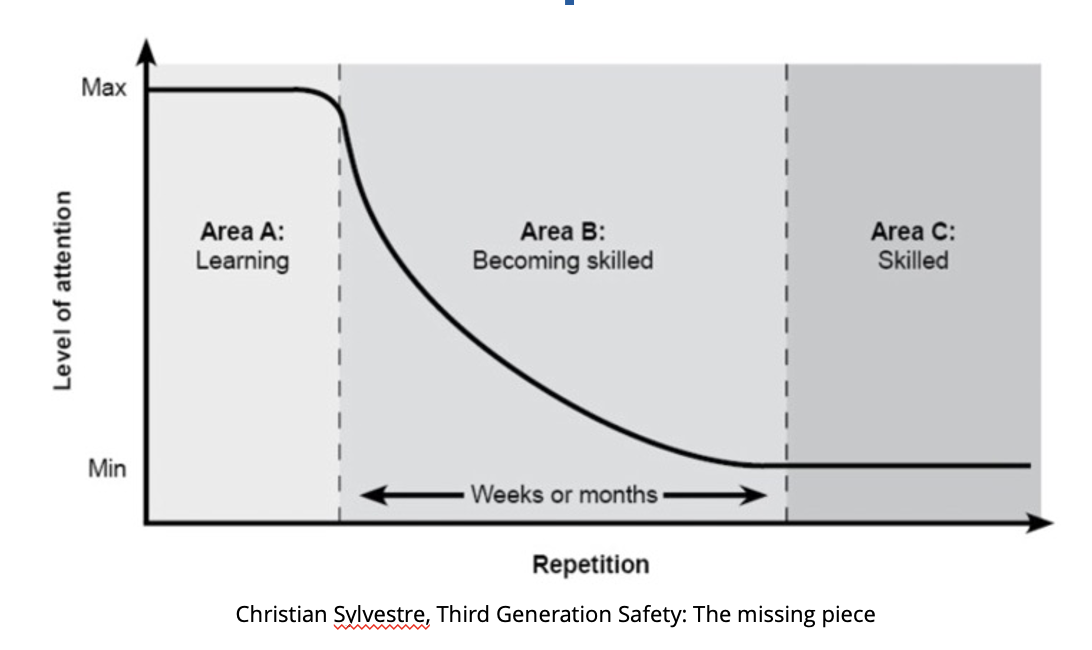

This is a real conundrum because in many cases we aren’t actively aware of how much attention we are devoting to the task, we are unconsciously competent. This diagram from Christian Sylvestre that shows when we are learning something new, we pay a lot of attention to the situation, and as we build up experience over time, we start to pay less. This shifting of attention is a double-edged sword because it means we can become complacent, a term often applied when things go wrong, however, we often call this same process efficiency if things go well!

The positive side of this shifting attention is that we learn what are the really important things to look out for, and then use our widened capacity to notice what else is going on around us, like the wreck survey, where our teammates are, what is happening to the environment, the cave we are travelling through and so on.

The more mental capacity we have from being proficient in technical skills and non-technical skills, the more we are able to devote to what might happen in the future by looking around us and matching patterns based on experiences to make a better decision. That is what the next question and answer are about.

How do we really make decisions in uncertain situations?

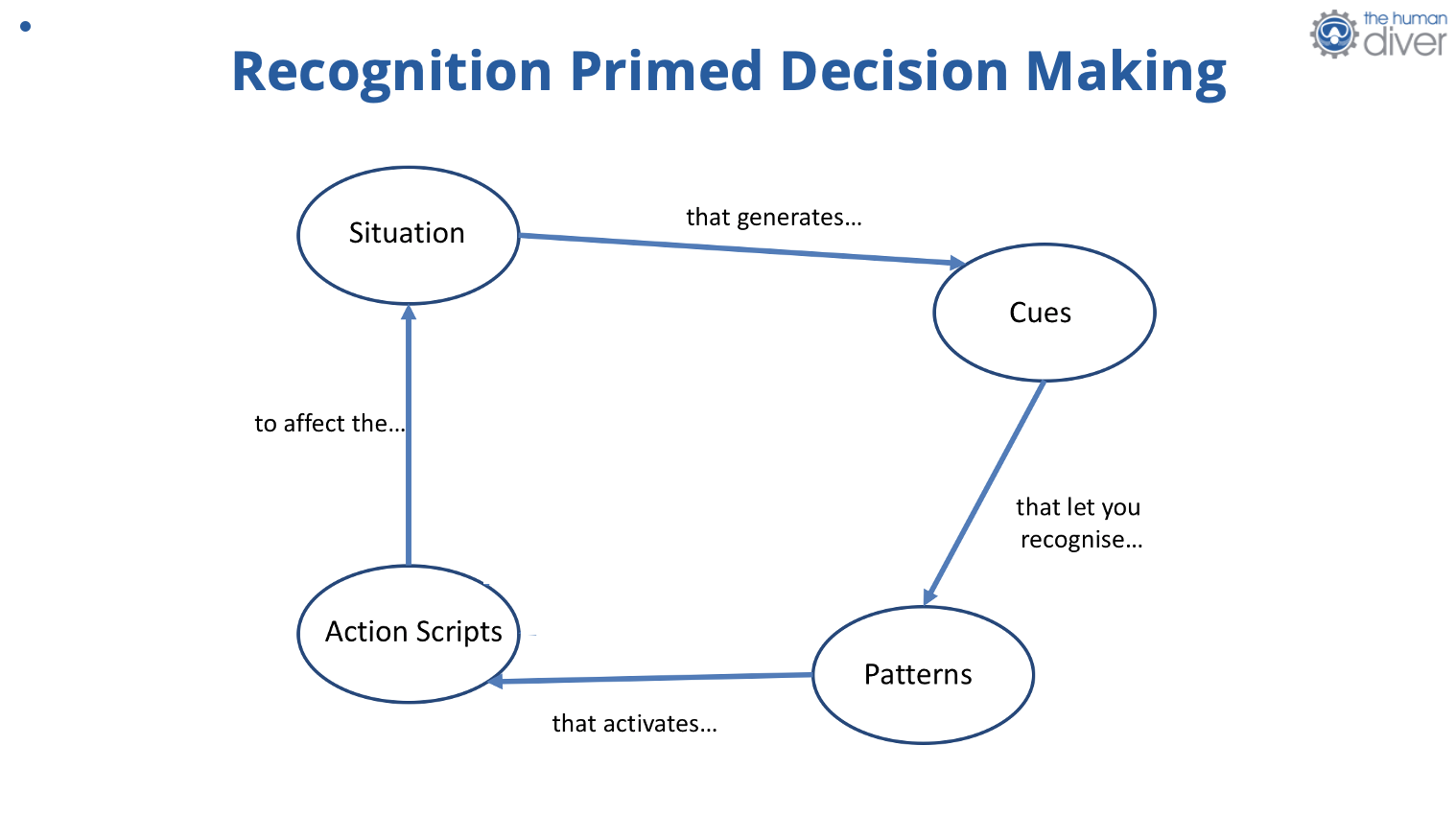

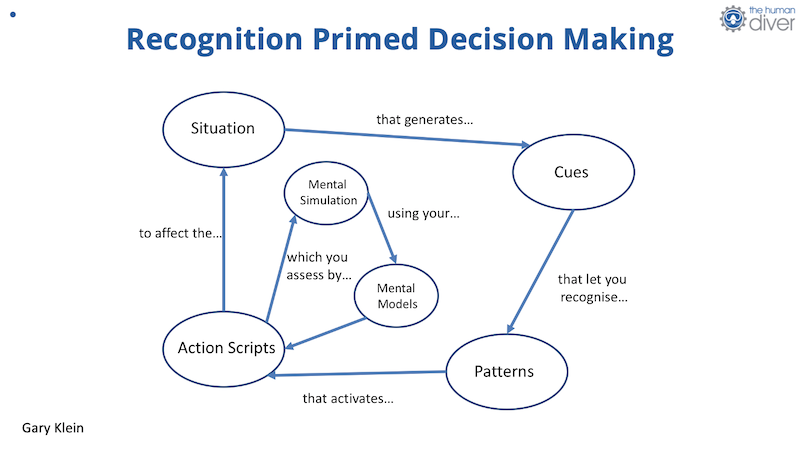

For that, we are going to look at another model. This model is called the recognition primed decision-making model from Dr Gary Klein. We recognise something in the scene which primes us to help us make a more accurate decision. However, for us to recognise something, we must sense it and process it against a pattern or image we have in our brains, and then create a match. The match doesn’t have to be perfect, but close enough to allow us to carry out the action we think we want to carry out. The closeness of match depends on how much time we have, a term called satisficing, it is ‘good enough’.

The model starts with an outer loop: we have a situation that generates some cues. These cues could be visual, audible, tactile, taste or smell. For example, a doorway on a wreck, or the shape of a pile of silt in a cave, or a large number of exhaled bubbles from your student. These cues are then matched against patterns or schema stored in our brains from previous experiences. Based on the match, we then decide to do something and that action is based on a script developed during previous practice or what we have read/seen we should do. Once the action is executed, the situation changes and we then see if the outcome is what we expected, if not, we go around the loop.

How we decide what action script to run is based on our previous experiences and this is what the inner loop of this model provides. The more models we have, the more subconscious mental simulations we can run to see if it is the right thing to do. If we only have one experience, we don’t have many choices. If we only have a hammer, the world looks like a bunch of nails to hit! Research showed that experts, or very experienced operators, were able to make decisions more quickly than novices or journeymen, those who were developing. Experts were able to identify key elements in the scene more quickly, and importantly, and they often didn’t even realise they were doing it.

Our brains don’t work in a slow, logical way most of the time. We are very efficient pattern matchers. The more correct patterns, the greater the chance we will be right. The wrong patterns, the wrong decisions.

How do we know we’ve made the right decision?

This boils down to effective feedback loops. To supportive effective feedback and debriefs, we have to have a psychologically safe environment. The feedback needs to be timely so we can remember the context. The feedback needs to be about actions, not the person if it is to be heard by the recipient. Experience can also help us shape and facilitate the debrief by providing a structure. It is difficult to know how relevant what you heard or saw was unless someone is providing some guidance. All of this requires a culture of learning.

Summary

To close, experience is important because it allows us to make more accurate decisions in uncertain situations. From research, the error rate in novel situations is between 1:2 and 1:10, not great odds when you are underwater! Practising the same skills in the same place can give you expertise but that is not the same as experience. Get in the water, in different locations, learn new skills or techniques, read more and watch educational videos, all to increase the number of mental models you have to pattern match more accurately and more quickly. Just like the real experts out there.

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a training and coaching company focused on educating and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website.

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.