At a system level, we don't learn from diving fatalities, and here's why

Divers and instructors don’t learn because it requires investment and change, and that is hard. Organisations don’t learn because the operational or 'local' safety problem is not theirs.

This blog summarises the free webinar I gave earlier this year, which looks at the death of 18-year-old diver Linnea Mills through a human factors and systems lens. The blog was written as there was another fatality of a young woman in the US last weekend. I have no details before anyone asks. At the same time, while I don't have details, I am confident that the factors and systems/human factors conditions present in the Linnea Mills case will be present in this event.

It does not point a finger at a single person to blame. Instead, it asks how normal people, doing what made sense at the time, were caught in a web of gaps, drift, and weak defences. This local rationality applies not only to the individual diver and instructor, but also to everyone in the diving system, including agency staff.

The goal should be clear: look to learn (and change) in a way that helps your next dive team, instructional team, or dive centre team avoid the same traps.

For those who don’t or won’t read the entire blog or watch the webinar, the simple answer is that this is not a single-person issue; it is a systemic one. The problem is that no one takes a system view of an event like this for a couple of reasons: there isn't a learning-focused 'investigation' process, and because there isn’t someone ‘outside of the system’ to lead the change. Unless there is a major, emotional or politically relevant event, change has to come middle-out, or bottom-up. Unfortunately, there is no organisational incentive to change. Individuals, instructors, and agencies all have the tools available to them to create change, but is there a desire to take them and apply them, given the poor financial state of the industry? As a friend of mine said to me yesterday, "The diving industry doesn't have enough money to have a safety culture." This quote and what a safety culture means will be the subject of another blog.

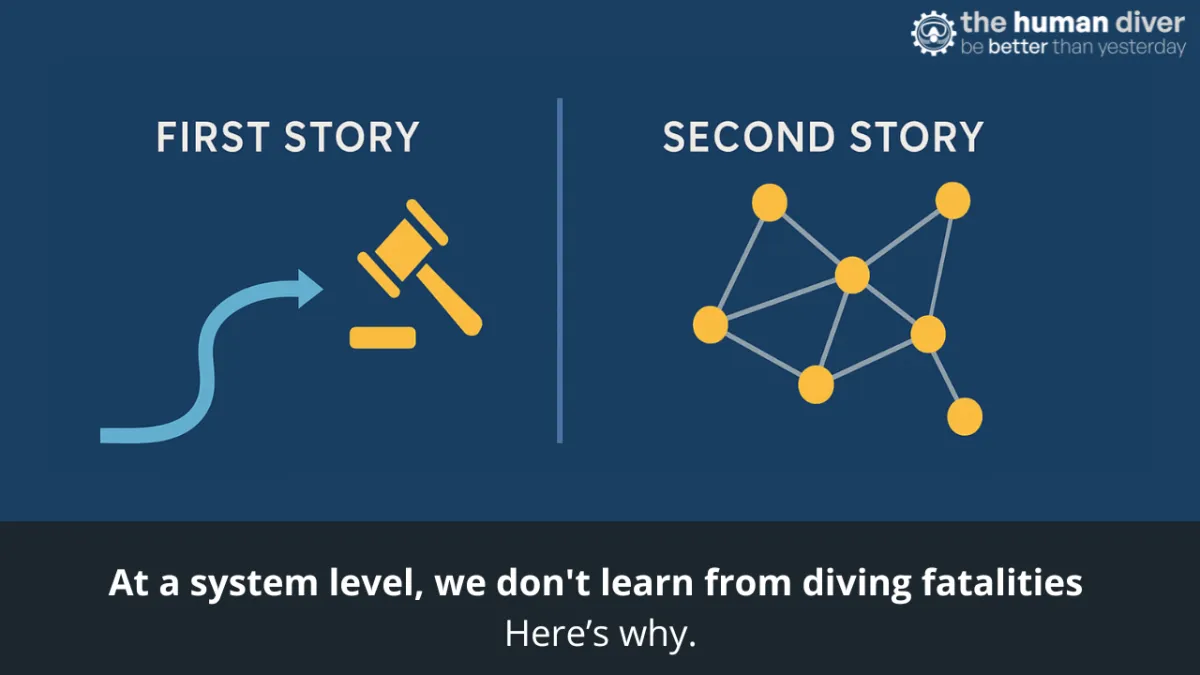

First story vs second story

The webinar starts by separating ‘first stories’ from ‘second stories.’ First stories are neat and short. They use counterfactuals, words like ‘failed to’, ‘should have’, ‘lack of situation awareness’, and ‘poor leadership’. They feel satisfying because we know the outcome and can join the dots backwards. We've found someone to blame; it's not us. Move on.

Second stories are messier. They explore goals, tensions, trade-offs, and the context people were working in. Only second stories can really help us learn. However, to get them, we need both psychological safety and a just culture; otherwise, the stories go underground, and we continue to have the same issues and the same commentary ‘Why aren’t we learning?’

How systems drift

The webinar shows that in a hazardous environment, like diving, nothing is 100% safe, and so we build margins to help reduce the likelihood of an adverse event. The margin is large enough so that we can detect an issue and correct it in time. However, without effective feedback, the margins get eroded as other priorities like money and time take priority. Over time, people, teams, and organisations ‘practically drift’ away from standards, often without noticing, because nothing bad has happened - yet. That drift is common in high-risk work and shows up in diving, too. When margins shrink, time compresses, and the system fails fast. Practical drift can explain how two USAF F-15 fighter jets shot down two US Army Blackhawk helicopters in Northern Iraq thinking they were Iraqi Mi-24 Hind helicopters, even though they had ‘visually identified’ them.

The topic of ‘normalisation of deviance’ is discussed along with where it came from.

The diving industry has repurposed the term ‘Normalisation of Deviance’ to focus on people breaking rules and getting away with it, eroding safety margins until they have an accident. However, the original concept behind this term comes from the Challenger space shuttle loss and the book ‘Launch Decision’ by Diane Vaughan, describing the term as a system issue, not an individual who breaks rules. No rules were broken in the case of the o-ring failure, yet the organisation had slowly accepted an increase in risk as being normal. Stakeholders had socially accepted the drift. NASA had also shifted the question from

- 'Show me why it is safe to launch’ to

- ‘Show me why it is unsafe to launch’

Minimums had become targets. Compliance can give an illusion of safety if feedback loops are weak and paperwork protects the organisation more than the worker. In our context, worker = diver. There are many examples of ‘Normalisation of Deviance’ in diving at the organisational and diver levels, and there will be a much longer article on that shortly.

The case: what lined up

Linnea turned up for an Advanced Open Water “adventure dive” that included a drysuit experience in winter conditions. She was significantly overweighted, carrying about 45 lb of lead, when she needed much less. Furthermore, her drysuit inflator could not connect to the hose supplied because it was a different fitting. There were significant sunk costs in terms of time and money, and resources available. She entered freezing water without a working suit inflator, began to sink, and drowned in a remote lake. These are the facts that set the stage for potential deeper learning, but have not.

Standards and supervision also played a role. At the time, an AOW class could be run under indirect supervision, while a dedicated drysuit course required direct supervision. Mixing class aims and supervision levels created confusion about who was watching whom, and what ‘good’ looked like for a novice in a drysuit.

The location was remote. When things went wrong, the only way to get a phone signal to call for help was to drive roughly 11 miles through the park at dusk/night to get a phone signal. That matters when we talk about Emergency Action Plans (EAPs), response time, and the capacity to fail safely. A rhetorical question - if nothing goes wrong, why do you need an EAP?

Changes were made to training agency materials, but fundamental issues remain:

- Inexperience/lack of competence of new instructors without formal supervision or mentoring,

- The process by which instructors can self-certify to teach once they’ve undertaken a certain number of dives remains. Doing something is not the same as teaching someone how to do it.

- A quality management system that requires a significant failure to occur before something is investigated. 'Happy sheets' don't really tell you much about performance.

Work-as-imagined vs work-as-done

Another theme is the gap between what is written down and what actually happens. Policies and manuals are tidy; real dives are messy. This model of feedforward and feedback helps us see the multiple levels that exist in a high-risk system: regulator, agency, centre, instructor, diver. My research showed that the feedback channels are rarely effective in identifying the gaps between what should happen and what does happen, for a whole bunch of social, cultural, and commercial reasons.

Using a ‘Jenga tower’ metaphor, the webinar shows that systems always have holes and gaps but they still remain stable. This happens because we rely on people and teams to bridge the gaps and create ‘safety’ dynamically. However, the ability to manage safely like this only works if the materials we are using are sound, the social, cultural and technical environments is understood, and the individuals and team are competent for the task. It should be noted that there is a huge gap between being competent and being compliant, and the diving industry does not have this squared away, despite having ISO standards that say effective feedback is provided to manage risk and drift.

Risk, liability, and human goals

Divers and instructors often treat ‘risk’ management as liability management through the use of forms, waivers, and compliance. But how we manage risk and uncertainty ‘in the moment’ is driven by many things, not least the goals we are rewarded or punished for, like progress or certifications, pride, finishing the task, keeping the schedule and to cost.

When things go wrong, if you focus on looking for ‘human error’ e.g., complacency, lack of situation awareness, poor communication, inadequate leadership etc., you will find it. If you look for equipment faults, you’ll find those. A different way to improve learning is to take a systems view and ask, ‘What were people trying to achieve? What made the next step seem reasonable? What conditions made it harder to do the ‘right’ thing and easier to do the ‘wrong’ thing? That lens broadens the learning opportunities beyond simple non-compliance. Note, conditions aren’t just environmental, like visibility, temperature, and current, but also social, technical, and cultural.

“We cannot change the human condition, but we can change the conditions in which humans work.”

“We cannot change the human condition, but we can change the conditions in which humans work.”

James Reason.

One of those conditions is authority gradient, and this is linked with power dynamics in a group or team (and wider to the training organisations). When asked about weight and configuration, Linnea reportedly said, “I guess I will be okay.” That line speaks to trust and deference. Telling students to “speak up” is not enough when the social and instructional signals say, “follow me.”

A forthcoming ‘Top Tips for Diving Instructors’ blog focuses on this very point – creating the conditions and space for speaking up. While the link will be ‘dead’ now, it will be live on 3 September.

Capacity to fail safely

"Safety is not only the absence of accidents. It is the presence of barriers and defences, and the capacity of the system to fail safely" - Todd Conklin.

In diving, that means more than ‘don’t make mistakes.’ It means building layered defences: competence and experience of all supervisor/leadership staff within the team, equipment compatibility checks, realistic weighting and buoyancy lift, functioning communications across the team, and practised & validated EAPs. The ultimate evidence of capacity is saying, “We are not diving today because of XYZ.”

Match supervision to the real task, not the label. A drysuit “experience” inside another class can look simple on paper and complex on the day. Treat it like a drysuit course: direct oversight, shallow water time, and prove the basics work before open water. Note, this isn’t just about drysuit training; this is about stacking courses with different goals and objectives within the same activity. If you combine activities, the likelihood is that time will be reduced for each activity. While the skills may have been demonstrated, are the students competent for unsupervised diving after class? Another example might be when the visibility is poor, an instructor and assistant decide to dive two waves for the student group to reduce student numbers and maximise supervision. However, this means the time in the water can be reduced from 40 minutes for a dive to 20 minutes for a dive, leading to a commensurate loss in experience. It still meets the standards though…

Check compatibility, not just presence. ‘Has an inflator hose’ is not the same as ‘this hose locks onto this valve and the gas flows as it should do.’ Build a pause into your pre-dive flow to connect, disconnect, and test equipment under pressure. This is especially relevant with rental gear or mixed brands. For supervisors/dive centre managers, look at how long it actually takes to do some of the checks needed, not just force instructors/staff to cram the activity into an ‘available’ time.

Weight for control, then verify. Overweighting limits options when it comes to buoyancy control. For every one kilogramme of being overweight, you have one extra litre of gas to manage. If you do a 30m/100ft dive, you now have 4 extra litres of gas to manage when you leave the bottom. What if you were 5 kilogrammes (10 lbs) overweight? Weight checks should be routine, documented (to mitigate memory failures), and re-checked, especially when conditions change (new suit, salt/fresh, cylinder type, etc). Don’t push a new drysuit diver straight into deep, cold, or low-viz water - they are unlikely to be able to say no. If you’re a parent, you will have an influence over your child’s behaviour, especially if training is linked with a vacation taking place very soon… As the instructor, have the difficult conversations.

Design EAPs for where you actually are. If a mobile call needs an 11-mile drive, plan for that. Who leaves, who stays, who coordinates, and what kit goes with them? Run short drills so everyone knows the route and roles. Better still, choose a different location, and if you can’t do that because there is something important to see/do there, then get equipment that can communicate.

Mind the gradient. Give students clear permission to pause or stop. Ask real check-questions (“What would you change before we go?” or use the TEDS open question acronym). Use language that reduces deference and invites candid concerns. This is what psychological safety is all about. Giving space and time for the challenge. Five blogs for you here on this. Blog 1. Blog 2. Blog 3. Blog 4. Blog 5.

Strengthen feedback loops. Debrief every dive, even if it ‘went fine’. Explore conditions and weak signals, not just outcomes. Just because you had a good outcome, it doesn’t mean the dive wasn’t a mess in someone’s head. Stories are the fuel of learning; you can’t fix a secret. Create spaces where sharing does not feel like self-incrimination, and the easiest way to do that is to lead with a story of your own. However, don’t turn that story into a ‘Look at me, I’m a hero’ – be humble.

Beware “plan the dive, dive the plan” as dogma. Plans never survive first contact. Reward adaptations that keep people safe and teach when to back out without shame or sunk-cost pressure. Consider feeding this back to the organisation, although my research shows that this rarely gets considered if it goes counter to the organisation's goals and aims.

Raise the bar above minimums. Minimum standards are not performance goals. If your system focuses on and rewards ‘meets the standard’, ask what extra checks, mentoring, or scenario practice would add real resilience. More on this in the Diving Talks video linked above about 'illusion of safety.'

Why the above matters

The hardest part of this tragic story is that little here is new. Overweighting, gear mismatch, remote sites, thin supervision, and weak EAPs have been present in many fatalities, albeit not all together. The patterns repeat because change is hard, and incentives are misaligned. That is exactly why we need the second story, the courage and structure to tell it, and the leadership to effect change. To those who say you can't do change, you can. Colleagues of mine working in child welfare in the US have managed to save lives, prevent burnout, and change state legislation by applying human factors and system safety.

Here’s a challenge for you personally: move past the tidy explanations and focus on building capacity within your dive staff, dive teams, and develop systems that can spot trouble, adapt early, and, if needed, fail without tragedy. That is the path to being better than yesterday.

If this resonates—if you teach, guide, supervise, or just want safer dives, watch the full webinar. Bring your team. Use it to start a different kind of conversation at your centre: one grounded in stories, systems, and practical steps you can take before the next dive.

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver. Along with 12 other instructors, Gareth helps divers and teams improve safety and performance by bringing human factors and just culture into daily practice, so they can be better than yesterday. Through award-winning online and classroom-based learning programmes, we transform how people learn from mistakes, and how they lead, follow and communicate while under pressure. We’ve trained more than 600 people face-to-face and 2500+ online across the globe, and started a movement that encourages curiosity and learning, not judgment and blame.

If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider the first step in developing your knowledge and awareness by signing up for free for the HFiD: Essentials class and see what the topic is about. If you're curious and want to get the weekly newsletter, you can sign up here and select 'Newsletter' from the options.