Top Tips for Diving Instructors: Leadership - Creating the space for others to be heard

Sep 03, 2025Are you being heard? Are you creating the space to be heard?

At the end of the season, we took a mixed group of fun divers to the Farnes Islands (United Kingdom). ‘Fun’ divers plus two sets of students who were finishing off some training programmes with ‘real world experience’. The forecast wasn’t great, and the water was unsettled, but the captain thought we might find a spot to dive. On board, we had everyone from ‘salty sea dogs’ to new divers who were already looking a little green.

We found a site that was technically diveable – diveability was ‘validated’ because another boat already had divers in! But the swell was rolling, the tide was pushing, and the safe dive area was small. The other concern I had was getting back on the boat, given the conditions.

The instructors had the ‘should we/shouldn’t we?’ conversation. My gut said no, partly because of a previous close call here, and this time, the team agreed: not safe enough, dive called. I explained the decision to the divers. Most nodded, and I even saw a few relieved faces.

On the way back, I kept asking myself, “Why hadn’t anyone said they were uncomfortable before we decided?” The newer divers later admitted they didn’t know enough to question the plan, but they’d have followed us in despite being nervous. Experienced divers didn’t want to look like they were “chickening out,” some thought they could handle it, and others didn’t want to waste the trip. There were so many cognitive biases at play here!

We realised that the authority gap between instructional staff and students meant no one spoke up. And to me, that’s a problem. We can’t have divers feeling they can’t question a decision.

*This scene-setting story was from a previous blog but has been modified slightly to get the learning points across.

But it’s not just about the instructor-student dynamic anymore

Diving instruction is inherently hierarchical. You're the instructor, the one trusted to be the expert. They're the student, the learner, and their role is to improve. That power gap, whether intended or not, shapes what gets said, what gets hidden, and who feels safe enough to speak up.

In today’s diving world, status and influence are shaped by social media followings and recommendations, brand affiliations, and who you know, not just your technical competence or the instructor certifications you hold. Imagine you're on a liveaboard, standing next to someone with thousands of followers and a reputation as a ‘legend’, are you really going to challenge their technique, decision, or something they’ve just said? For most divers, especially newer ones, the answer is no. In the last 18 months, I have personally walked away from unsafe diving activities because I was afraid to challenge the status quo of ‘heroes’ in their environment.

The Problem with Heroes

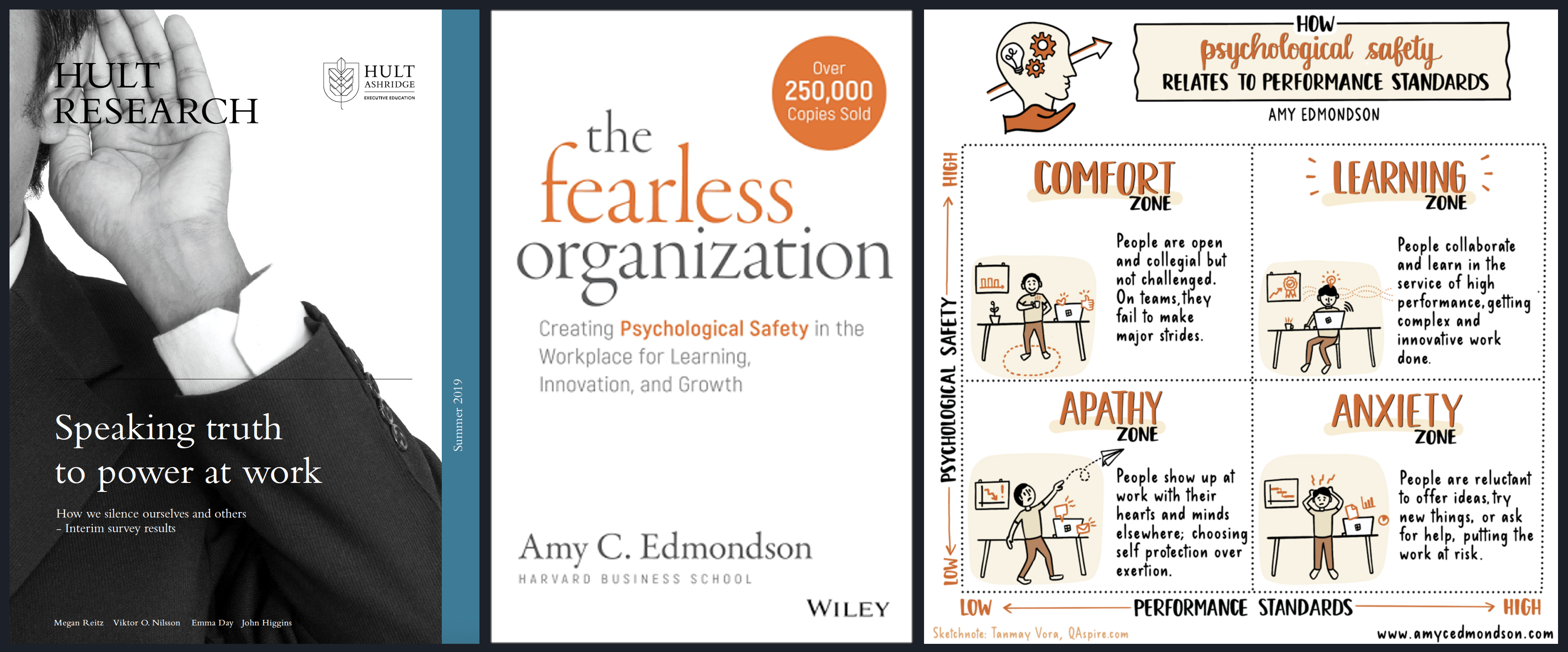

You only need to look at social media to see that the diving industry loves heroes. That’s not necessarily a bad thing; diving needs passionate and experienced practitioners. But problems arise when those heroes become unchallengeable. As Reitz and Higgins note in their world-leading research, we are constantly assigning "titles and labels" to people, and those with high-status labels, like Instructor Trainer, Explorer, Ambassador, get listened to more than others. The trouble is that those labels can mask fallibility – everyone makes mistakes, irrespective of their experience and title. As Amy Edmondson has highlighted, when considering whether to speak up or stay silent, silence is seen as the safer option, as the problem might go away, but if the question is asked, the (social) result is found straight away.

In one of the studies by Reitz, senior leaders were often three times more likely to believe people spoke up around them than those actually working underneath them reported. This ‘optimism bubble’ applies just as easily to industry heroes. Their presence can unintentionally suppress openness in classrooms, on boats, and in post-dive debriefs. Who’s going to call out a bad decision or unsafe practice when it comes from someone who posts videos and photographs online showing them ‘doing their stuff?’ and not having any (public) incidents or accidents?

Diving is not immune to advantage blindness, when those with status are unaware of the privileges their label gives them. They assume others can speak just as freely, not realising that the room has already gone quiet.

Tribalism and Nepotism: Loyalty Over Learning

Another complicating factor is tribalism. Dive centres, agencies, and even social media communities can foster strong group identities. “We do things this way.” “Our agency believes…” “That’s not how we teach it.” The terms family, cult, and brotherhood are not unusual in social media posts and marketing materials within the diving community. These tribal norms can become barriers to open conversation, especially when combined with nepotism, which is the subtle (or not-so-subtle) favouritism shown to insiders.

In tightly knit instructor communities, students and even junior instructors often don’t just fear embarrassment; they fear exclusion. If you challenge a practice that someone’s buddy, business partner, or agency mentor supports, you may find yourself quietly sidelined. Your progress stops. I spoke with one senior agency staff member who asked, “What are the instructors afraid of? Why won’t they challenge me?” My response was that these senior organisational members held the professional progression of the more junior instructors in their hands. I also highlighted that the higher you are in an organisation, the harder it is to see these barriers, as there is less to lose when a challenge is made.

And this is where the research from Reitz and Higgins really hits home - the biggest reasons people stay silent are social, not technical (they have the tools - they just can’t use them). Across thousands of respondents, the top two barriers to speaking up were:

- Fear of being perceived negatively.

- Fear of upsetting or embarrassing someone else.

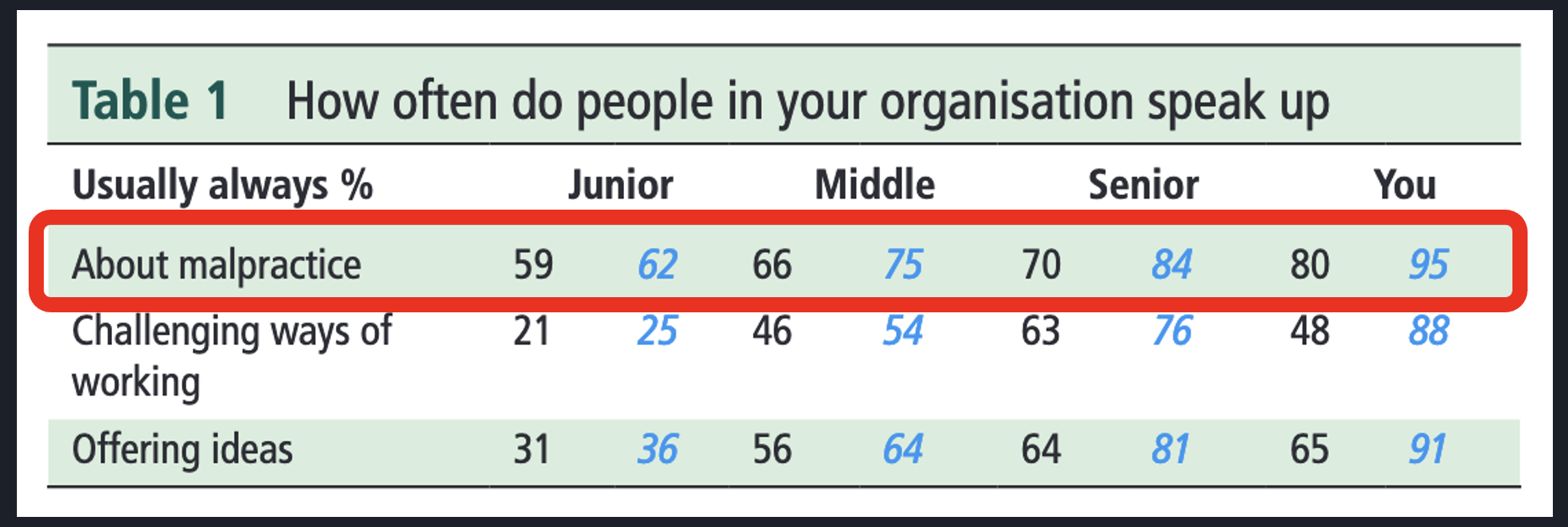

Both are amplified in environments where status and loyalty are currency. In their survey, 34% of junior employees said they would stay silent about malpractice. This isn’t ‘disagreement’ or ‘a different approach’. They were concerned about malpractice. (Blue text, more senior. Black text, more junior. Note, if you're a senior leader, 95% think something will be said, but if you're more junior, only 80% think something will be said. Compare that to what junior people really think on the left side of the table.)

We don’t have data for the diving sector, but Reitz and Higgins’ research spans many domains. Why would diving be any different? Especially given the tribalism and commercial competitiveness that is present, the latter was highlighted in my MSc research. Both the Linnea Mills case and the Brian Bugge case involved an inability to speak up and challenge the status quo.

How many times have you heard of ‘names’ breaching standards, but there is an inability to challenge them or the agency they are teaching through? This is something I unearthed in my MSc research too. If the stories are kept quiet and not documented, they didn’t happen.

The answer from the agencies is that self-reporting feedback forms would highlight these issues. However, they are fraught with challenges. Speaking from personal experience, post-course assessments were changed to allow the comments to be shared with the instructors in a timely manner (as long as the student gave permission). While most of the students were happy to share their comments, some were afraid they would upset their instructor and be ‘left out in the cold’ and wouldn’t be able to dive with that community. It wasn’t until I had had a personal conversation with the students, thereby creating trust, that they allowed the comments to be shared. Without sharing critical feedback, instructors (and the organisation) cannot learn and improve. The absence of an accident (the metric of safety in diving) does not mean the system is safe.

Why Listening Up Matters More Than Ever: Making the Shift

Instructors, trainers, and leaders must realise that creating a safe learning environment isn't just about making it easy to speak up; it's about being worthwhile speaking up because 'I' will be heard. This means actively working against the dynamics of power, popularity, and politics. It means taking off the metaphorical ‘badge’ every once in a while, and asking:

- “Have I made it safe for someone to challenge me?”

- “Am I rewarding conformity or curiosity?”

- “Do I listen more to people who look and sound like me?”

The TRUTH framework developed by Reitz and Higgins offers a useful way to unpack what’s going on:

- T – Trust: Students and instructors need to trust that their voice will be valued by their instructor and their agency, respectively, not dismissed or ridiculed. Yet many who are in leadership positions trust their own opinion more than others, especially those with less experience or social capital.

- R – Risk: Speaking up carries risk, especially in tribal or hierarchical cultures. The risk might be embarrassment, loss of status, social harmony, or limits placed on professional development. If instructors (or agency leadership) don't actively lower the perceived risk, silence is going to win, and safety can (and will) be compromised.

- U – Understanding: Politics isn’t just for politicians. Understanding the social rules and agendas, who can say what, and to whom, is vital. Divers may know the “right thing,” but not the “right time, place, or person” to say it to. I know this from personal experience as an ‘outsider’ in the diving industry. The problem is that there are very few forums in which issues can be raised in a manner that allows constructive critique to be raised.

- T – Titles: Titles and labels (instructor, instructor trainer, course director, explorer, ambassador…) affect who gets heard. Those with more “decorated” names carry invisible authority that can silence others, even when they're wrong. And if issues are raised, they can easily be suppressed through public opinion and tribalism.

- H – How: Even when the intention is good, how we create space for speaking and listening matters. If you only accept feedback during formal debriefs (if they take place), you might miss the quiet truths spoken over coffee/beer, during gear rinsing, or a WhatsApp conversation.

Personal reflections

I know that I have ‘authority’ in the diving domain relating to human factors in diving. I have heard I have a cult around me. I know that I create situations (not normally intentionally!) where it can be hard to challenge something that I have said.

I also know that when a challenge does come in, I thank the person, provide my perspective and evidence for that perspective. Do I get it right all the time? No. Do I know when I don’t get it right? Sometimes. I work with the Human Diver team to create a challenging (to me) environment, but I know there are things not being said, and that is both saddening and frustrating – but also life. At the same time, life is a learning journey. When bad news comes in, I know I have an emotional trigger, and I then try to reframe it as ‘How can I use this to be better than yesterday? How can I use this to improve the team?’

The bottom line?

We need to rewire our diving culture to one where listening isn’t just polite, it’s foundational, where speaking up isn’t about bravery, it’s about belonging, and where reputation doesn’t shield people from challenge, it earns them the humility to hear it. Given the socio-political nature of the world today, that isn’t going to be easy. But as a good friend of mine, Guy Shockey, regularly says to me, ‘Every storm starts with a single raindrop.’ Be that rain drop in your team, your community, or your training organisation.

Practical Takeaways

Here are five simple but powerful ways diving instructors and instructor trainers can foster speaking up, building trust, and listening better:

- Open with Curiosity, Not Authority. At the start of a course or dive, ask: “What would help you feel confident speaking up if something doesn’t feel right?” This signals that you welcome input, not just compliance.

- Use the Debrief to Listen, Not Just Teach. After each dive, let students speak first. Ask: “What did you notice? What felt off? What would you change?” Avoid jumping in with corrections too soon; it shuts down reflection. This is hard, especially when time is limited.

- Recognise Power Dynamics. Remember, your title carries weight. Sit or crouch down to eye level during conversations, avoid standing over people, and be mindful of body language that might feel intimidating.

- Watch for Shut-Up Signals. Avoid multitasking, checking electronic devices, or cutting people off. Making eye contact, having an open posture, and a nod can make a huge difference.

- Value Informal Chats. Some of the best insights come outside the formal sessions. Take time during surface intervals or kit-up to ask: “Anything you’re unsure about?” Trust and psychological safety are created in the small interactions that happen, not the big shows of power and knowledge. Be consistent with the personal engagement.

Summary

Creating a learning environment isn’t just about giving students knowledge; it’s about giving them a voice that will be heard. As instructors, we have the privilege and responsibility to guide their diving skill development and their confidence to speak truth to power. When students or instructors trust us enough to share what they’re really thinking, that’s when the real learning begins. Fundamentally, "we cannot fix a secret" (Clive Lloyd).

Be the reason someone speaks up.

References:

Speaking Truth to Power at Work. Reitz and Higgins. 2019. https://www.meganreitz.com/blog/reitz-m-nilsson-v-day-e-and-higgins-j-2019-speaking-truth-to-power-at-work-hult-research

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver. Along with 12 other instructors, Gareth helps divers and teams improve safety and performance by bringing human factors and just culture into daily practice, so they can be better than yesterday. Through award-winning online and classroom-based learning programmes, we transform how people learn from mistakes, and how they lead, follow and communicate while under pressure. We’ve trained more than 600 people face-to-face and 2500+ online across the globe, and started a movement that encourages curiosity and learning, not judgment and blame.

If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider the first step in developing your knowledge and awareness by signing up for free for the HFiD: Essentials class and see what the topic is about. If you're curious and want to get the weekly newsletter, you can sign up here and select 'Newsletter' from the options

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.