Top Tips for Beginner Divers: Teamwork

Jul 08, 2025When “Buddy” Was Just a Label

Two divers were paired up for a short dive on the house reef. It was Jack’s second trip away after his OW course, having completed 20 dives since he first learned to dive. Laura, his buddy, was on holiday and had around the same number of dives as Jack. The dive centre instructor briefed the dive location and a rough plan: 15m/50ft max depth, a square route along the reef wall, and back to the pier to exit. Pretty simple.

They both did a giant stride entry from the pier and gave each other the okay signal on the surface before descending and starting on their way. Although nothing had been formally agreed, Jack took the lead. He was excited to be back in the water and wanted to find the octopus that he’d read about on a Facebook group he was a member of.

Unfortunately, he didn’t check if Laura was ready to go. She paused, adjusting her mask strap, but he didn’t see this. He started swimming, assuming she’d just follow.

Laura struggled to catch up but did make it. Jack was scanning the reef, his attention focused on trying to identify where the octopus might be, and in the process, he missed the subtle signs that Laura wasn’t quite comfortable, even though she was just behind him now.

A minute later, she tugged his fin hard. Her mask was leaking, and she was anxious. Laura put the thumb up, and they surfaced and had a brief discussion.

Jack felt embarrassed. Even though he was embarrassed, he said thank you to Laura for calling it, recognising the need to reinforce that anyone can thumb/call a dive at any time for any reason, something he heard from a tech diving friend of his.

As he floated there, he realised he hadn’t really been a “buddy”. They’d been two divers next to each other, but not a team. They hadn’t talked through who would lead, how fast they’d go, how long their gas was likely to last, or what to do if something went wrong like gear configurations. They could see where the pier was, and because Laura still wasn’t happy, they made a surface swim back, signalling to the centre staff that everything was okay in the process.

Once their gear was sorted, they met in the beach bar and debriefed. They agreed on signals, who’d lead the next dive, and how they’d check in underwater. This made a big difference to their enjoyment and comfort on the next dive.

The Theory: Teams Don’t Just Happen

Teamwork isn’t about being best friends or diving with someone for years. It’s about clarity, shared expectations, and trust. The seeds of trust can be sown between two strangers with a simple conversation on a boat or at the quayside. But often it requires one person to take the lead in terms of starting the conversation.

Beginner divers often assume that because diving is “a buddy sport,” teamwork will just happen. But unless we’re intentional about it, we fall into what The Human Diver team calls ‘assumed coordination’. We think we’re on the same page, but we haven’t checked. Assumptions are normal, but sometimes they can catch us out. We need to validate the critical assumptions.

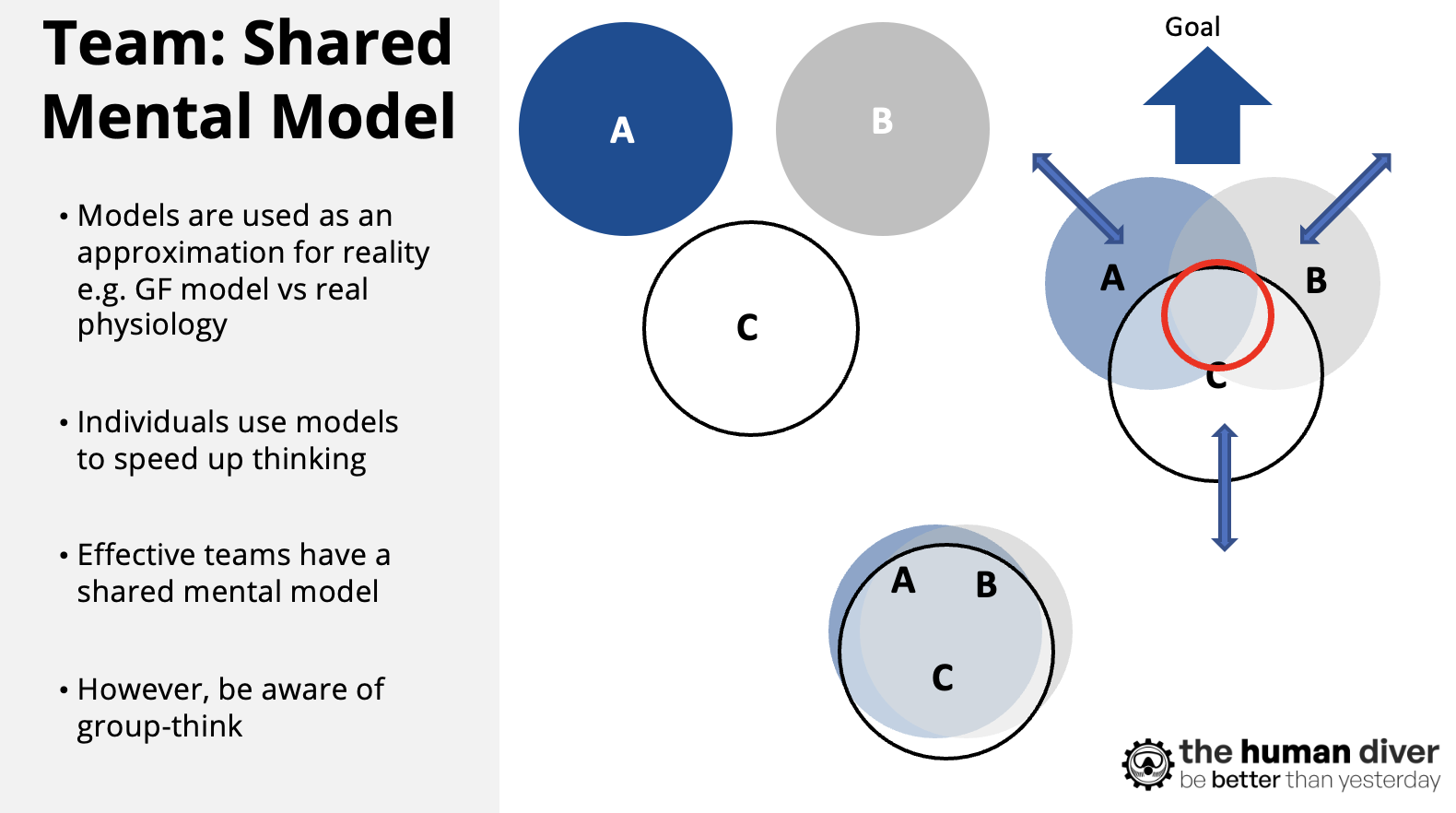

Good teams create and maintain a shared mental model of what is happening and what is likely to happen next. This is a shared understanding of the plan, the expected environment, the tasks at hand, and each other’s roles in achieving those tasks or the wider objectives of the dive. That way, when something unexpected happens, everyone’s already aligned, and additional mental effort is not needed to problem solve while executing the immediate actions.

Bruce Tuckman’s model — forming, storming, norming, performing — describes how teams grow. New divers are usually in the “forming” stage. That’s when politeness and uncertainty dominate. People hesitate to speak up, afraid of looking silly or too assertive. But that politeness can hide problems. In diving, that can mean missed signals, diver separation, or unnoticed stress.

As well as clarifying things before they get in the water, strong teams also debrief. They reflect on what went well, and why (so it can be replicated), and what needs to be improved and how that will be done. Fundamentally, they learn together. Every dive becomes an opportunity for feedback, and then improvement as the feedback is applied to the next dive or trip.

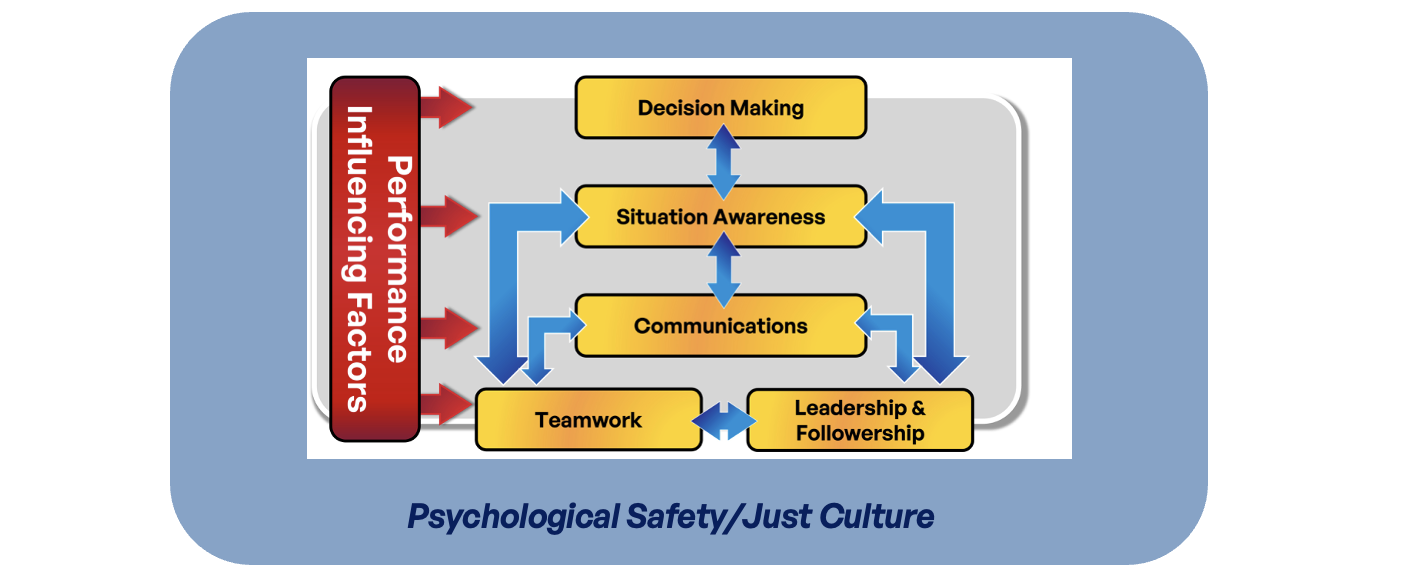

And let’s not forget the other non-technical skills which help divers achieve successful outcomes and have fun dives: communication, situation awareness, decision-making, and leadership. All of these are interwoven in effective teamwork. You don’t have to be a team of experts to be an effective team, but you do need to build the habits that let you be better than yesterday.

Finally, teamwork is about mutual accountability. We look out for each other and call each other out. We do it because we care about the other members of the team. My team member might spot something I didn’t, and if they call it out, then I should thank them, not do anything that would stop a future call being made.

Practical Tips: Build Better Teamwork from Dive One

Here are four simple tools you can start using on your very next dive:

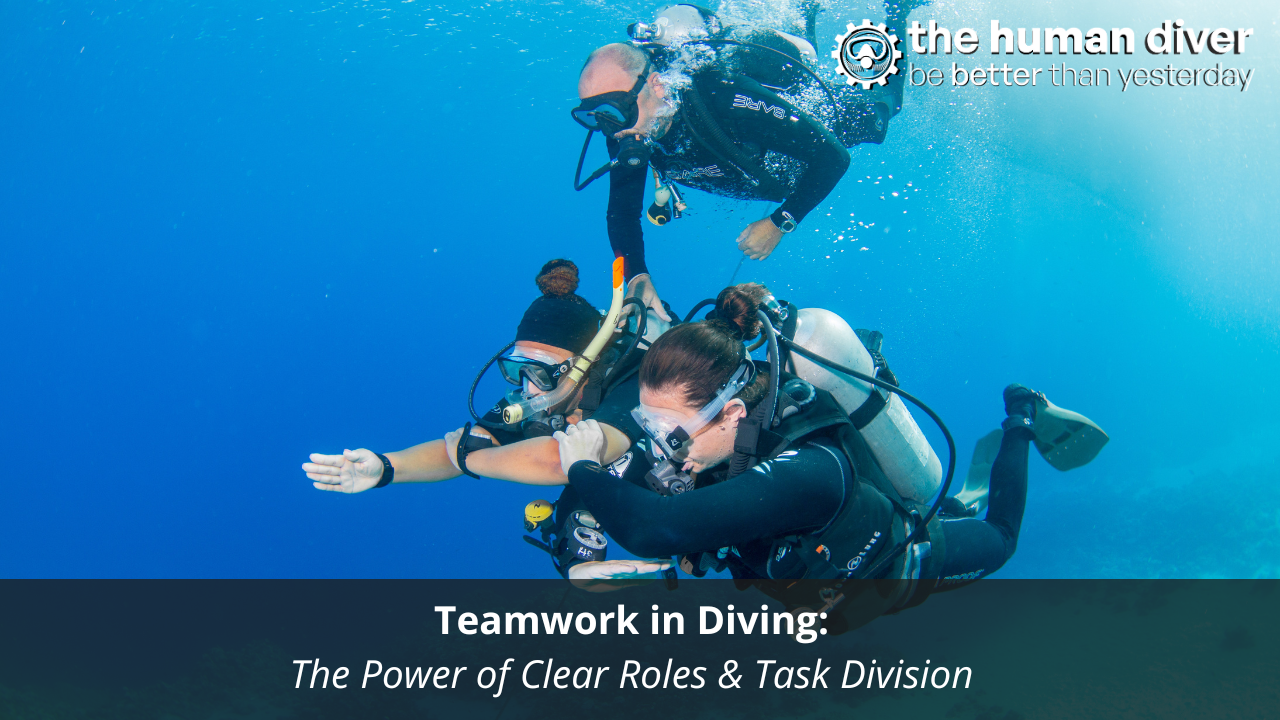

- Agree on Roles and Intentions Pre-Dive

- Who’s leading? Who’s watching navigation? Who carries the dSMB? Who is going to put it up?

- What’s the plan? What are the turnaround/end dive criteria? How will you communicate if it changes?

- Don’t skip this chat, so many dives have ended badly when someone thought someone else was doing something.

- If this is difficult, start with vulnerability – “The last time I was on a dive, I forgot a few things. I’d like to make sure that doesn’t happen again. Can we run a quick plan and brief?

- Set Expectations for Communication

- Use simple signals and agree on what they mean.

- Decide when you’ll check in — every 5 mins? Every change in direction?

- Ensure that everyone knows “thumbs up” means “go up,” not “ok”, close the communication loop by demonstrating it.

- Use a Short Debrief After Every Dive

- Two minutes is enough:

- What surprises did we have?

- What went well? Why did it go well?

- What should we do to improve next time? How will we do that?

- Be specific, not general. “Communication was good” is not a good debrief point, as we don’t know what to replicate next time. “When you replied with a questioning finger to my direction of travel, that was much better than “OK” which some other divers might have done because they felt they couldn’t ask a question.”

- Ask questions. Offer feedback. Say, “I was unsure when you…” or “What I am hearing you say is…”

- Thank your buddy for calling out issues. It’s not about blame, it’s about learning.

- When providing feedback, focus on the behaviours and actions, not the person themselves. “You were late on that stop.” Vs “Your timing appeared to be on that stop.”

- If you’re leading, invite input: “What have I missed?” goes a long way.

Summary

Teamwork for beginner divers doesn’t have to be complicated, but it does need to be deliberate. Don’t assume that a shared air source makes you a team. Build trust. Talk about the plan. Stay connected underwater. Debrief together. Every small step creates a safer, more enjoyable dive — and sets you up for a lifetime of learning beneath the surface.

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver. Along with 12 other instructors, Gareth helps divers and teams improve safety and performance by bringing human factors and just culture into daily practice, so they can be better than yesterday. Through award-winning online and classroom-based learning programmes, we transform how people learn from mistakes, and how they lead, follow and communicate while under pressure. We’ve trained more than 600 people face-to-face and 2500+ online across the globe, and started a movement that encourages curiosity and learning, not judgment and blame.

If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider the first step in developing your knowledge and awareness by taking the Essentials of HF for Divers here website. If you're curious and want to get the weekly newsletter, you can sign up here and select 'Newsletter' from the options

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.