We see what we think we’re looking for

On 14 April 1994, two USAF F-15C fighter jets engaged two US Army UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters in Northern Iraq thinking they were Iraqi Mi-24 Hind attack helicopters and shot them both down with the loss of all 26 people on board. This is despite both highly trained fighter pilots visually identifying the helicopters as they flew past within 1000 ft of them. Furthermore, an Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) was on station providing oversight of the airspace to give them cues about hostile threats.

How could this happen?

Probably, more importantly to you as you’ve got this far is what has this go to with diving? You aren’t operating in hostile airspace and you’re not flying a multi-million-dollar jet (admittedly a few of you might be doing this!). But what you do all the time is make decisions based on incomplete information, when under some form of time pressure and influenced by social and peer pressure to achieve a goal or reward.

This short article will look at how it made sense for the pilots on that day to ‘visually identify’ two Mi-24 Hind helicopters but shoot down two UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters, and how this is relevant to you as a diver, an instructor, a member of an agency who puts training materials together, or finally, someone involved in incident investigation.

Background

From 1991 to 1996, coalition forces enforced a no-fly zone in Northern Iraq to provide protection for a humanitarian operation on the ground. US Army UH-60 helicopters operated in the low-level airspace, below 400ft, supporting ground forces and moving VIPs and staff around. The F-15s were part of the multiple air packages that would ensure there were no hostile forces in the airspace. The Air Interdiction fighters, which included F-15s, were supposed to be the first aircraft into the operational area. However, on many occasions, the UH-60s undertook their missions before the fighters arrived on scene. While this deviation was known about by the AWACS, the F-15s didn’t know this because of a breakdown of communications, both prior to launch and also during the fateful mission.

The Shootdown

On the day itself, when the two UH-60s flew into the operational area, they should have changed a setting on a black box (IFF) that would identify them as friendly to AWACS and coalition fighter aircraft. However, at some point in the previous 2 years, the planning and operational teams of the UH-60 had been missed off the paperwork where this change in procedure had been detailed and no one in the AWACS had noted this omission over these 2 years when the helicopters entered the area without the correct code. To a radar-equipped aircraft, this IFF would indicate it was unknown or hostile. Another form of IFF, Mode IV, which was fitted to the Blackhawks didn’t appear to work on the day.

As the UH-60s left one base for another, they disappeared from the radar screen of the AWACS as they were in mountainous terrain. This was noticed by one crew member, who handed it over to another crew member who didn’t notice, but then the display ‘timed-out’ as it should have done, and the contact was lost. When the UH-60s’ tracks reappeared a few minutes later, they were treated as an unknown as no one had made the link with the previous helicopter mission. At the same time, the lead F-15 picked up a contact and started to interrogate it with their own IFF equipment. None of the responses came up conclusive as being friendly, so Lead asked his wingman to check using their radar and IFF equipment, and he confirmed them as not being friendly forces. They then descended to low level to visually identify the contacts as part of their rules of engagement. The formation of two started about 10km behind the helicopters, with No 2 of the F-15s approximately 4km behind Lead. As they overtook the helicopters flying at around 500kts, they were 360kts faster than the helicopters and passed 1000ft to the left and 500ft above.

The lead pilot called ‘VID Hind, correction, Hip….no Hind’. and pulled up to check his ‘cheat sheet’ of recognition diagrams as he wasn’t quite sure. He then called ‘Confirm Hinds’. No. 2 came in at the same speed and called ‘ID Hind, Tally 2, lead trail, TIGER 02, confirm Hinds.’ AWACS responded ‘Confirm Hinds’. Both aircraft pulled up, circled back and then lined up for their air-to-air missile shots. Lead did a final check of ID using the IFF and it came back as negative, not friendly. Lead fired on the trailing helicopter and No. 2 took the lead helicopter. Both aircraft were immediately destroyed with a total loss of life.

From start to finish the engagement took just 8 minutes.

There were multiple failures within this complex system that led to the loss of life. AWACS crew training and team competence. Incomplete voice and electronic communications between helicopters, F-15s and AWACS. Misidentification of the UH-60s by the F15 pilots. You can read a really detailed and comprehensive review in Scott Snook’s book ‘Friendly Fire’. One of four key areas that Scott looks at is the pilot misidentification.

The ‘cause’ of the misidentification?

The model of situational awareness (SA) developed by Mica Endsley lists one of the many factors that helps influence our SA as ‘expectation’. In the case of the F-15 pilots, they had ‘expected’ to see enemy helicopters and so believed they were doing the right thing:

- There wasn’t supposed to be any friendly forces in the operating area, so these must have been enemy helicopters.

- The IFF, both Mode 2 and Mode IV, didn’t identify the aircraft as friendly, so must have been unknown or hostile.

- AWACS hadn’t told them there were (US Army) helicopters in the area, so these can’t have been friendly.

- The helicopters were on a different frequency, and all friendly aircraft were supposed to be on the operational area frequency, so these can’t have been friendly.

- All friendly aircraft were marked with national flags, these didn’t have any. However, the six US flags that were marked on each helicopter were on the sides and so not visible from 500ft abeam and 1000ft above as the pilots passed by.

- The long-range fuel tanks looked like the rocket pods on a Mi-24 from above because only the tip and tail were visible, and ID training photos didn’t include these fuel tanks, so must have been Mi-24s.

- The photobooks / cheat sheets that the pilots had for ID’ing helicopters only had pictures of helicopters taken from the ground looking up not from the air looking down.

When we have an incomplete information set, and time is pressing, we use mental shortcuts or heuristics to bridge the gap between unknown and believed. Time was limited in this case because the 360kt overtake speed meant they were covering approximately 6 miles per minute, a mile every 10 secs. Plus, they were much closer to the ground than normal, which meant that there wasn’t much ‘brain’ time allocated to visual ID, rather it would have been about not hitting the ground.

We often hear about ‘seeing is believing’ when describing some amazing event or observation. Karl Weick describes another phenomenon – believing is seeing. “Beliefs affect how events unfold when they produce a self-fulfilling prophecy. In matters of sense-making, seeing is believing”. Furthermore, Brunner says “The more expected an event, the more easily it is seen or heard.”

These were two highly trained, professional aircrew and they believed that they were intercepting and had ID’d two Iraqi Mi-24 Hind gunships. What about the rest of us mere mortals who go diving, who instruct, or who train others? What does this ‘believing is seeing’ look like?

- A recreational diver has a pony cylinder strapped to their primary cylinder for use as an emergency cylinder. They complete a buddy check while on a RHIB, roll backwards, and descend. After 8-10 mins the diver appears to run out of gas, swims up and away from their buddy, tries to ditch his weight belt but it catches on the dive knife they have on the outside of their calf, and they cannot ascend. They drown. The pony cylinder is empty. They had been breathing the pony regulator from the surface. Neither the buddy or the diver realised that they were breathing the pony regulator and when they ran out of gas, their immediate response was to spit out their current and go to the pony regulator and start breathing. That cylinder was empty, and they panicked. Unfortunately, even though they did the right thing, ditch their weight belt to be positive, this snagged, and they were still negative and out of gas.

- A cave diver is swimming through a cave system they haven’t been before. They see the line go ahead and then go right, the tie-off appears to be on the rock ahead. They turn right and follow the line. They swim on a little and notice that this section of cave doesn’t have the structure they were expecting. They signal to their buddy to turn around. On returning to this part in the cave, they notice that they have made a jump from the main line to another line without realising it because the line junction was behind a rock, and they did not see the main line disappear into the distance.

- A rebreather diver is using a different model of rebreather to one which he has used for most of his rebreather diving, the one which he has developed motor and cognitive skills around. The Head Up Display (HUD) on his current rebreather indicates a flashing red LED if there is either high pO2 (above 1.6) or low pO2 (below 0.4). After some navigation difficulties and a team separation, he is now alone in a different part of the cave to the plan. From the rebreather data log, it appears there is CO2 breakthrough leading to CO2 narcosis. At this point in the dive, he has also just descended quickly shortly after injecting a slug of O2 into the breathing loop, leading to a spike in pO2. The CCR now shows a red LED. At this point, somewhat irrationally, the diver injects O2 into the breathing loop! The hypothesised reason is that his previous CCR only showed a red LED when there was a low pO2 situation. The diver kept manually injecting O2 into the loop until he drowned. The hypothesis is that he was trying to inject diluent into the loop, but the manual injects were different to his previous rebreather. The final pO2 in the loop was more than 5.0!

Believing is seeing.

Our visual sensory system is incredibly powerful when it comes to overriding our logical thought processes. You just have to Google “visual illusions” to get a myriad of examples. If you are involved in any form of incident investigation, I’d recommend you look at this paper “What-You-Look-For-Is-What-You-Find” as expectations shape what we think caused the accident/incident. Language can also shape our expectations too.

It would be easy to say, don’t make assumptions, especially as hindsight bias and ‘common sense’ can lead to the well-used phrase, ‘Assumptions make an ass out of u and me!’ (ASS U ME) However, we must recognise that assumptions also make the world go around at the pace it does. As such, we have to learn what are the assumptions that we can take without fear of a major failure, and those which we have to validate to make sure that if are wrong, we don’t have a catastrophic failure.

Improving the Situation

We can improve the chances of spotting and validating erroneous assumptions beforehand by:

- Analysing breathing gas before putting the regulator on our breathing cylinder on the day of diving.

- Having an effective pre-dive brief that covers potential areas of confusion.

- Using closed-loop communications, topside and underwater. Using open questions to check understanding – questions that can’t be answered yes or no. Start the question with ‘Tell me/us…’, ‘Explain to me…’ or ‘Describe what…’. The use of ‘OK’ (index finger and thumb in a circle) doesn’t mean you understand the message, it could mean that ‘I am okay, and I’ve seen your hand signal’.

- Completing a post-dive debrief where you look at not just what went well and what can be improved, but also why it went well (so it can be replicated) and how the improvement will happen.

Learning technical skills is not enough to keep us safe in diving (or any high-risk activity for that matter!). The non-technical skills programmes developed for The Human Diver are based around developing a shared-mental model within the team, and by checking and validating assumptions, groupthink is reduced. Understanding our cognitive variability will not stop assumption-based adverse events, but it will reduce their likelihood.

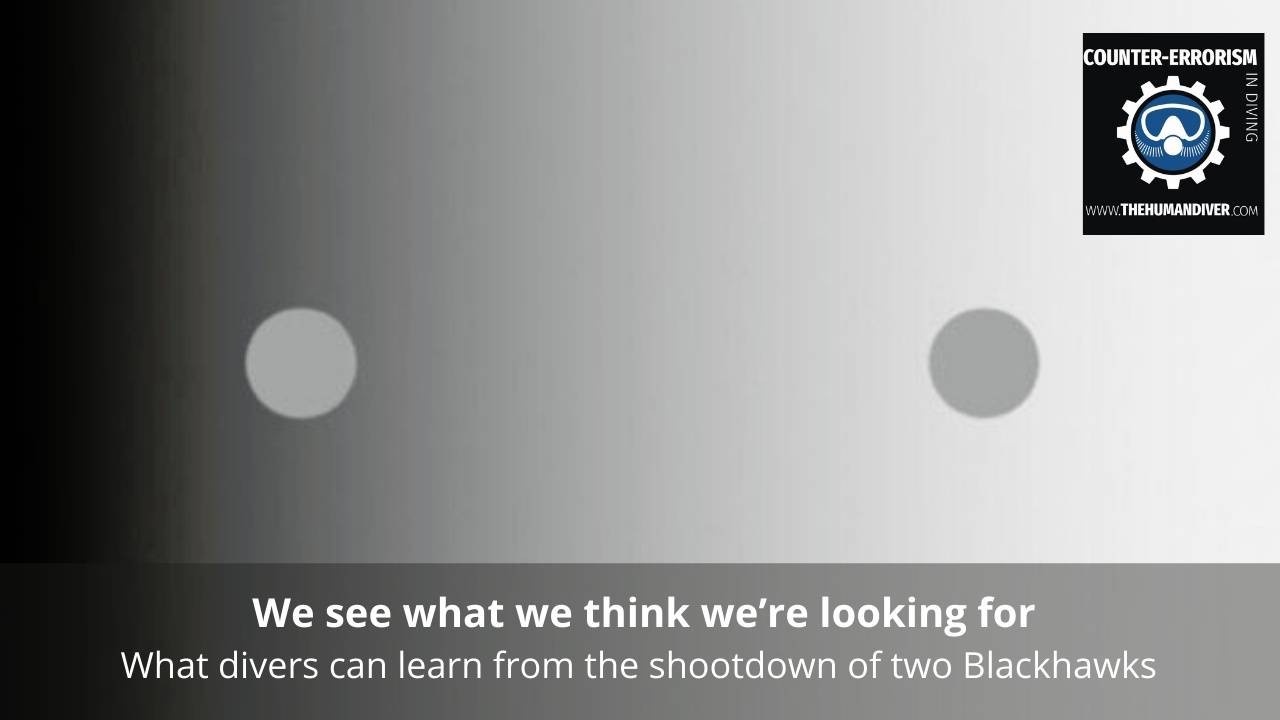

If you hadn't realised, the main image is a visual illusion. Both of the circles are the same colour! https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/a32905285/classic-optical-illusion-contrast-explained/

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a training and coaching company focused on educating and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website.