HF in Diving for Dummies: Part 2: 'Human Error' - Why we need to look deeper

Aug 14, 2022The problem we have when we call something going wrong ‘human error’ is that it is a bucket that we can throw everything we think is wrong into, but the term doesn’t help us learn. Sure, the diver, the instructor, the skipper, or the dive centre manager did something that ended up not going as they expected, but unless we know what was happening at the time, and immediately before, how do we stop it from happening again?

Saying things like “Pay more attention”, “You need to have greater awareness”, “Don’t forget your fins next time”, “Be clearer with your communication”, or “Make sure you don’t rush and take your time” might appear to be helpful because they seem to correct what went wrong, but they don’t take into account what was going on at the time and so learning rarely happens.

We can easily describe examples of errors, but what is a good definition? How about “an unintended outcome from a preferred behaviour” or just “something we didn’t intend to do”. We’ll discuss the ‘preferred behaviour’ bit at the end of this blog as that is important.

Professor James Reason, the guy who is known for the Swiss Cheese Model, noticed that one day in the 1970s while getting some cat food ready for his cat, he nearly spooned cat food into the teapot which was next to the cat’s bowl and ready for him to add some hot water. He thought about why this happened, especially as he realised that these sorts of issues happened in high-risk industries with much greater consequences than a dodgy cup of tea!

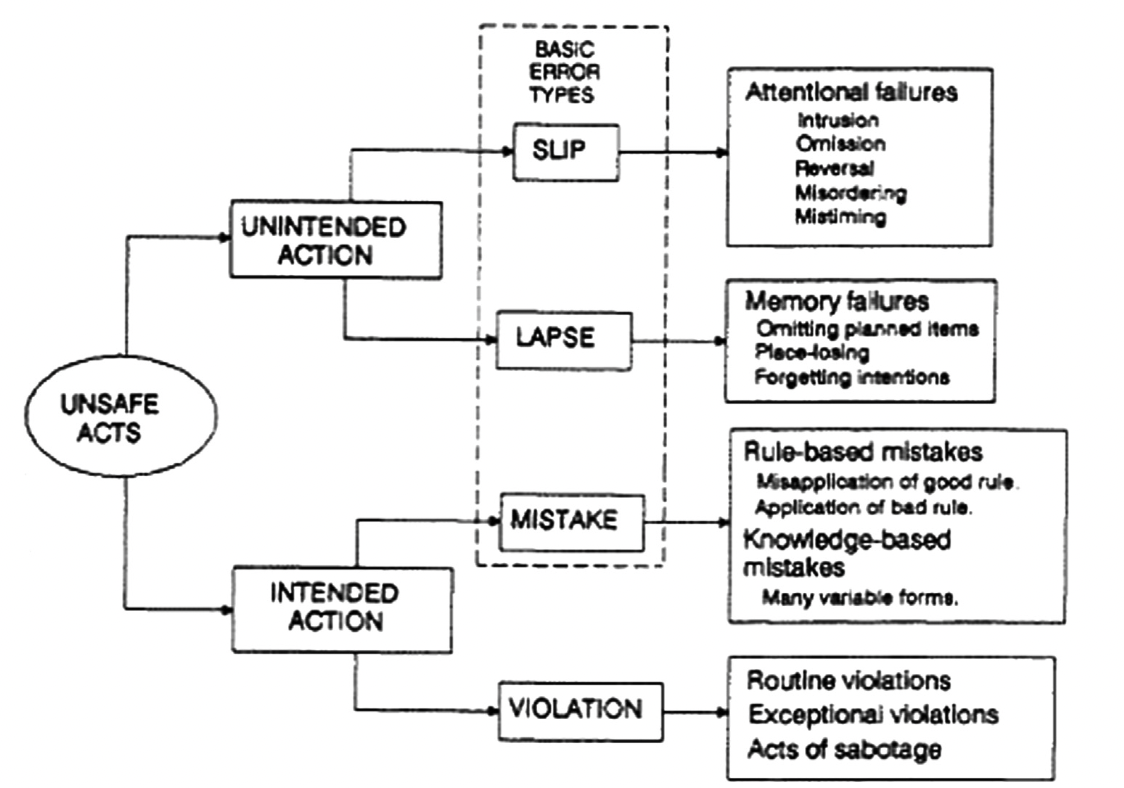

Reason came up with three groups of error types and a fourth special group called violations. The errors and violations were broken into unintended actions and intended actions.

Unintended Actions

- Slips. These were failures of attention. It might be that someone or something caused a distraction which led to the wrong thing being done or something being missed out, or there was a reversal or incorrect order in a sequence e.g., a diver attaches their drysuit feed after they’ve put their long hose in position, and in the process, they trap the long hose under the drysuit feed so it can’t be deployed in an emergency.

To reduce slips, we need to change the environment to reduce distractions.

- Lapses. These are related to failures of recall or memory. The operator might forget a planned item, they might lose their place in a sequence, or forget what they were supposed to do e.g., the team of divers are doing their final checks and the deck hand asks them a question about their run time and planned decompression. As they answer this, the team loses track of their progress and misses a critical item which causes a problem in the water.

The use of checklists can help prevent slips and lapses if they are carried out properly, otherwise, they can increase these sorts of errors. If a check is broken, it is restarted from the beginning to make sure something wasn’t dropped.

Intended Actions

- These came in two sorts; rule-based and knowledge-based. Rules-based mistakes are where the operator applies a bad rule e.g., using incorrect teachings to calculate the amount of gas needed for an ascent, so they run out of gas when a gas sharing ascent happens, or they misapply a good rule, e.g., they believe that their gas consumption rate at depth is 20 bar every 5 mins, however, they are using much smaller cylinders than normal and so run out of gas because they didn’t recognise the faster consumption rate. Knowledge-based mistakes are where the diver thinks they are doing the right thing, but it is the wrong thing e.g., turning around at a planned bottom time but not recognising that the current has picked up and they are now much further from the shot line and can’t ascend the shot and must do a free ascent.

- Mistakes can be reduced by completing an effective dive plan and then a detailed brief with open questions to check understanding. A debrief also identifies where the rules or knowledge didn’t necessarily match what happened on the dive, so the knowledge and rules can be improved next time.

Violations

- These are when it looks like a rule was broken on purpose. It could be because of an emergency or unusual event e.g., descending below the MOD of the gas to rescue another diver or a routine violation e.g., be on the surface with 50 bar, but the norm has become 25-30 bar so the divers can make the most of the bottom time on the reef. A special type of violation is called sabotage where there is genuine intention to damage something - fortunately this happens very rarely.

Note that since Reason put violations under the topic of ‘intended action’ the safety science community has recognised that routine violations are often signs of organisational weaknesses e.g., lack of quality control, lack of feedback, poor training materials, poor briefing, and normalisation of deviance.

Addressing ‘Errors’ to Improve Performance and Safety

If an investigation ends with ‘human error’, this is an opportunity to start looking into what sorts of errors occurred. You’ll probably find that many of these will happen when something goes wrong. Where was the diver’s attention pointing? What was distracting them? Why? Did they have a good understanding of the task at hand? If not, why not? Was their training incomplete? Was the brief poor? Had they made some flawed assumptions about this dive and not checked them? Was it the norm for people to deviate from standards? We are social creatures and therefore it is harder to conform to the rules than it is to conform to the social norm.

This final point links back to the first definition of an error: an intended action. What we think we should be doing isn’t necessarily the same as what the rest of the team or organisation think should be happening. This is what we mean by “preferred behaviour”. If the standards and behaviours are aligned, great! Remember that accidents and incidents happen as deviations from what is normally done, not just deviations from the rules.

The next blog in the Human Factors in Diving for Dummies series will look at what a Just Culture is and why we need it if we are going to learn from the different types of errors and violations that happen all the time.

Example

An advanced OC trimix instructor and MOD 1 CCR instructor was guiding an OC guest on a reef in the Red Sea. The first dive was relatively short which meant the gas consumed in their twinset was less than expected, and so the planned air top to bring the mixture from 28% to 25% didn’t happen. The instructor was busy getting the guest sorted and they never ran a dive brief for the second dive which was planned for 55m. Because the cylinders weren’t air topped, the instructor ended up with a pO2 of 1.82 at 55m because they still had 28% in their cylinders. Fortunately, they did not have an issue. They only realised the seriousness of the event after the dive. You can read a full account here. This story contains a number of slips, lapses, and mistakes, and could also include an unintended violation. Putting them all into the bucket of 'human error' or 'complacency' doesn't help the learning. However, if we look at the error-producing conditions, we are more likely to reduce the likelihood that this happens again.

Summary

The term ‘human error’ is widely used to describe a reason why something went wrong. However, it doesn’t help us learn because it only really says what happened and not how it made sense for the diver to do that thing which led to an unintended outcome. If you read ‘human error’ or ‘diver error’ as the cause, that is your opportunity to go digging deeper to understand ‘how it made sense for the diver to do what they did’.

Further Reading: Skybrary - Human Error Types This page also contains some interesting numbers at the end regarding the frequency of errors and the likelihood that they will be trapped before something bad happens.

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a niche company focused on educating and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website.

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.