Reframing The Dirty Dozen - Part 1

May 28, 2025Is it the human….or the system….or both?!

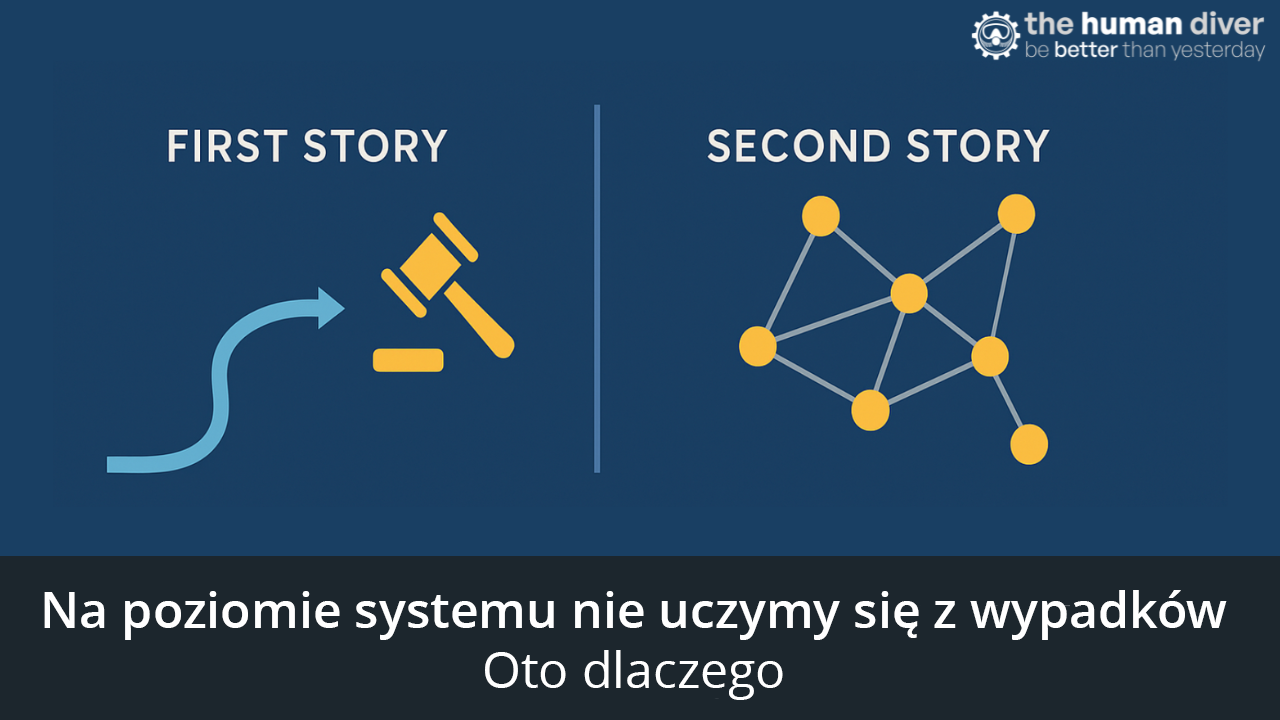

Humans like things to be simple. We like categorising complex ideas into groups, and putting them in order, or into lists. We can only take in a finite amount of information at any one time, so this is logical, it allows us to make sense of the world in a shorter time. The problem is that simplifying things often misses out crucial context. And when people only know the simple list, not the context, they may not learn how to apply the list correctly.

This week at The Human Diver we’ve been talking about the infamous “Dirty Dozen”, a list of 12 factors that has been used by organisations for decades to help improve safety. The issue with the list is that it is exactly that; a simplified list which misses a lot of the context that is needed to actually make a difference. On top of that, it contains absolutes “Don’t”, “Never” etc that aren’t always possible when we take context into account.

Because this list is still widely used, I’ve used it as a framework to look at the wider context i.e., the system and procedures that humans are working within that we need to be aware of in order to improve safety.

The term ‘The Dirty Dozen’ was developed by Gordon Dupont in 1993. They are not the only factors which lead to mistakes, errors and violations, but they certainly give you a focal point to identify conditions where 'errors' and 'violations' are more likely to occur. Different domains or even subsets within domains like aircrew, ramp-crews, and air traffic control within aviation have different ‘dirty dozens’ based on captured and analysed incident data. Unfortunately, no such data exists in diving which looks at factors which contribute to incidents and accidents. Consequently, the following is based on the original list and is not arranged in any specific order.

- Lack of communication.

- Distraction.

- Lack of resources.

- Stress.

- Complacency.

- Lack of teamwork.

- Pressure.

- Lack of awareness.

- Lack of knowledge.

- Fatigue.

- Lack of assertiveness.

- Norms.

While knowing what the issues are is a good start, it is important to develop and practice countermeasures to the Dirty Dozen, thereby reducing the likelihood of an 'error' or 'violation' occurring, or if an event does start to emerge, the 'error' is captured before it becomes too serious. As such, each topic will have concepts presented to help you prevent or mitigate the problem.

As you work through the Dirty Dozen, you will notice the interdependence e.g., lack of resources or miscommunication can increase stress and lack of knowledge can lead to reduced awareness, and this is one of the limitations of using a simple categorisation system.

As this is quite a long topic, I have split it into four parts, published over the next few weeks.

Lack of Communication

Poor communication is often a major contributory factor in incidents and accidents, and the need to improve communication is one of the key goals identified in The Human Diver classes. Communication refers to both the transmitter (speaker) and the receiver (listener) as well as the medium and the systems used. Communications are often assumed to be person-to-person, but dive computers, SPGs and CCR controllers all communicate information to the diver. In all cases, it is often assumed that the information has been understood by the receiver, either because the receiver made some assumptions about missing information, or because the transmitter assumes the receiver heard/saw and understood the message. With verbal communication, it is common that only some of a message is received and understood as our brains process words faster than we can transmit or receive them.

Countermeasure. For a dive to be successful and all the goals/tasks/limitations understood, information must be passed between team members, or the instructor and the student, as part of the 'learning' team. This can be started prior to the dive with a briefing. Using a model such as UNITED-C helps ensure the important information is shared but it’s important to make sure that everyone understands the plan by using open questions. The acronym TEDS can help here. (Tell me... Explain to me... Describe to me... Show me...) Underwater, sometimes the messages can be complex. If this is the case, write the message down. On land, verbal messages should be kept short with critical information contained at the start of the message and then repeated at the end. While assumptions are key to operating at pace, if there is not enough time allowed for checking understanding, critical information can be missed.

Distraction

Distraction is part of our modern lives. We are unable to perceive and process the vast amount of information available to our senses. As such, we filter and discard what we don’t think is important or relevant. Even worse, if something comes to our senses which looks really ‘interesting’, we start to focus on that and forget what we were doing before. Those distractions could be conversations, other people doing things around you, environmental issues like noise, wind or the cold, along with problems that need to be solved immediately, for safety reasons, like a piece of dive equipment falling over or about to blow away. Distractions can also be emotional or psychological in nature, like family issues or how you’re going to pay for the trimix bill!

Psychologists believe that distractions are the number one reason for forgetting things, and if you’ve forgotten to do something, unless something triggers the thought you forgot, it will remain forgotten! We have a tendency to think ahead. In many cases, that is a good thing, but this also means that when we return to a task, we think we are further ahead than we really are.

Countermeasure. Two ways to deal with distraction are to look at preventing it and then mitigating it.

- Prevention. Look at the situation in which people are working. If you are doing something critical (like assembling your camera or CCR), let your team or students know, and unless something is really urgent and can’t wait, they should hang back and come and find you afterwards. If you are constantly being disturbed because you are always needed, it’s worth looking at the tasks you are being called on for and seeing if it is possible to train others to do those in your place. If only one person is able to do a critical job within an organisation, that is a serious failure point and needs to be addressed. Consider factors such as location - would it make a difference if you were somewhere else (and is it possible to move)? Mobile phones are one of the most intrusive distractions, and silencing them is often not enough, as many of us habitually check them even when silenced. Hiding notifications from non-urgent apps (email and social media are the two most invasive) allows you to relax knowing people can reach you in an emergency, but hides the routine distractions that can be dealt with after the dive/class is finished.

- Mitigation. If possible, finish the task and then go to the ‘distraction’. However, if you are going to be drawn away from the primary task, put a mark or sign as to where you are in a sequence that is really obvious to draw your attention back to that. Checklists come into their own here. If you are using one and are distracted, I would recommend you go back two or three steps, as we have a tendency to overestimate progress.

Lack of Resources

If we don’t have the correct parts or tools to complete the task, as divers we often try to improvise with what we have. In many cases, it is fine and nothing happens. However, unless we understand the criticality of the components or the task at hand, then disaster can strike. Resources also refer to people, skills, experience, knowledge, etc, and a lack of these can interfere with our ability to complete the task safely and effectively. Even more important is that if the task is successful without using the correct resources, normalisation of deviance or normalisation of risk can set in (see Norms).

Countermeasure. When the proper resources are available and to hand, there is a greater chance that the task will be completed more effectively, correctly and efficiently. This might mean a small expenditure in the short term, but lead to safer divers and potentially saving money in the longer term when the botched job doesn’t need to go to a service or repair tech. If resources aren’t being provided, the organisation e.g., dive centre or training agency, needs to address the reasons why that is happening. Money is the most common reason, but can an organisation afford to pay for the consequences if something happens due to a lack of resources? There is a great quote from John Wooden, “If you don’t have time {money} to do it right, when will you have time {money} to do it over?”

Read part two here, part three here, and part four here.

Jenny is a full-time technical diving instructor and safety diver. Prior to diving, she worked in outdoor education for 10 years teaching rock climbing, white water kayaking and canoeing, sailing, skiing, caving and cycling, among other sports. Her interest in team development started with outdoor education, using it as a tool to help people learn more about communication, planning and teamwork.

Since 2009 she has lived in Dahab, Egypt teaching SCUBA diving. She is now a technical instructor trainer for TDI, advanced trimix instructor, advanced mixed gas CCR diver and helitrox CCR instructor.

Jenny has supported a number of deep dives as part of H2O divers dive team and works as a dive supervisor and safety diver in the media industry.

If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider the first step in developing your knowledge and awareness by taking the Essentials of HF for Divers here website. If you're curious and want to get the weekly newsletter, you can sign up here and select 'Newsletter' from the options.

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.