Joining Dots is Easy, Especially If You Know the Outcome

The short story. A technical instructor didn’t analyse their gas prior to a 55m dive which meant that they ended up breathing gas at 1.8 pO2. They survived.

The long story is what was written about in last week’s blog (read it here, as it isn’t as simple as this first sentence describes).

As you’d expect, there were numerous discussions online about this event. Those within the HF in Diving Facebook group were different to some of those that took place outside. Inside the FB group, there was a recognition that the diver should have analysed their gas, but there were multiple reasons why this slipped the instructor’s mind and therefore the sharing of the story was worthwhile, especially as others in the group had encountered similar situations. Outside the group, there were comments that this was a critical step/skill and because it was missed, it should be punished. Furthermore, admitting the story and then talking about it was considered unprofessional.

There are a number of biases that limit the learning from adverse events: hindsight bias, outcome bias, severity bias, confirmation bias and fundamental attribution bias. These have been described in other blogs so won’t be expanded here, with the exception of one, hindsight bias. The reason hindsight will be expanded is that it is a critical flaw we have that stops us from recognising and then learning from the complex environment we operate in.

20:20 Hindsight

We often believe that if we had the clarity that 20:20 hindsight gives us, we wouldn’t make the mistakes we or others make. There are a few problems with this statement. Firstly, we can never know exactly what is going to happen in the future, therefore the probability of us understanding what WILL happen in the future is not 100%. The other thing is that even if we know what LIKELY would happen given a certain scenario, there are often other pressures that prevent us from doing the RIGHT thing. Note ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ can only really be determined after the event because most people are trying to do the ‘right’ thing. They are being locally rational based on the information they have, and the pressures/drivers they face, along with the workarounds they have developed in the past to achieve their goals. This is normal human behaviour.

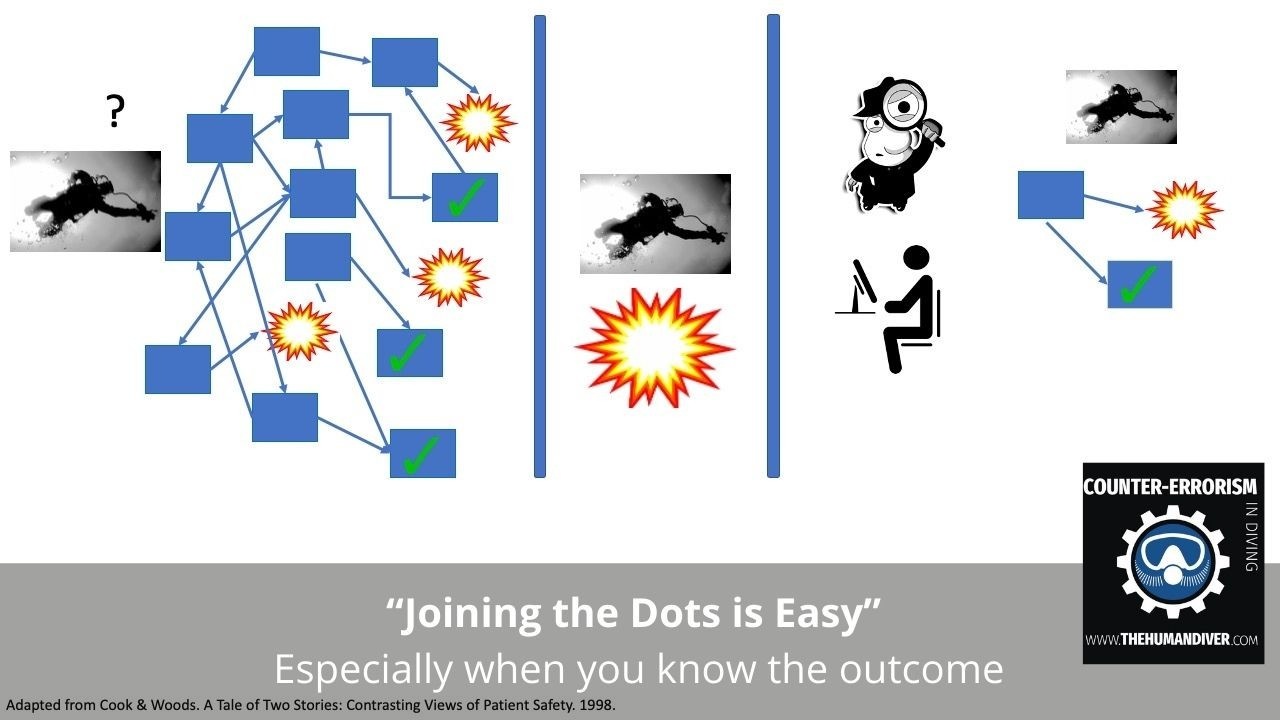

This diagram, modified from work by David Woods and Richard Cook, shows that after the event there is only one choice to be made, where the outcomes are ‘good’ and ‘bad’. Yet prior to the event, there are multiple competing goals with multiple potential outcomes – some good, some bad. We don’t know with 100% certainty what is going to happen.

As an example of these complex interactions, we can look at the events from 2017 where RaDonda Vaught, a nurse in Tennessee, administered a drug in error which led to a patient tragically dying.

The case has shown that there were multiple systemic issues that led to this ‘rational’ decision being taken by Vaught. This included recognisable error-producing conditions: time pressures, multiple patients, automated medication cabinet which didn’t easily dispense when needed, different form of the drug, fatigued staff, and lack of staff to cross-check dispensing. Discussions on multiple social media platforms show that these error-producing factors are present in many environments but due to the adaptability and resilience of individuals, the errors were trapped in most situations before a catastrophic event occurred. What isn’t surprising, but disappointing all the same, is that the nurse is being used as a scapegoat for systemic weaknesses, especially when fellow professionals state that workarounds are the norm to achieve the goals of the hospital. On 25 March 2022, she was convicted of neglect and negligent homicide where she is likely to get between four and eight years in prison. This link provides a very comprehensive account of the events.

Local Rationality

Incidents and accidents can provide the ability to understand ‘local rationality’ but only if there is a Just Culture present so the context-rich stories can be told. Stories that include deviations and discussion about the ‘rules’ that were broken. We must move beyond ‘they broke the rules’ if we genuinely want to learn about how events unfolded in the manner they did.

I am not a big fan of using diving fatalities to learn from because there is a significant amount of emotion present, normally there is some legal process that limits disclosure, and most importantly, the person with the most information behind ‘their’ local rationality is normally dead, so you can’t ask them questions. When fatal events are settled out of court, the learning nearly always stops.

One of the reasons that ‘rules get broken’ is because of the context in which divers and instructors operate. The following is an example of context. I undertook a brief survey last year to find out examples of the gaps between ‘Work as Imagined’ and ‘Work as Done’. A common theme was the problem of conducting Controlled Emergency Swimming Ascents (CESAs) during a class and staying within standards. A high-level requirement from the agencies is to have direct control of the students. For a task that requires students to be individually supervised, this can be achieved by having a DM, an assistant instructor or another instructor present to look after the divers who are not executing the drill. This additional person costs money, the cost of which is then passed onto the students in the form of higher class fees.

What happens if there isn’t that extra person? What if the dive centre doesn’t provide one, or there is a change in plan? What does the instructor do? Do they leave them on the shore? What if it is a long swim to the point where a CESA can be undertaken? If the divers are split, how does an instructor manage an emergency? What are the air and water temperatures? What are the surface conditions like? Do they leave the students on the surface or at the bottom? One instructor described how their Course Director had said there are pros and cons to both, and that you (the instructor) need to manage the risk as you (the instructor) will undoubtedly have to do this on your own!

I am sure that many of you will be reading this and say that the dive shouldn’t happen. At this point, we need to consider the tension that always exists between safety, money and manpower, a tension which is shown in the diagram below. We don't know where the accident line is, so there is a margin of error applied. (Page 7, Section 6 of this explains this in more detail) Safety can NEVER be the number one priority all the time for a company. If it was, it would go bust. This is what risk management is about. Risk management in diving is about dealing with uncertainties because hard, quantifiable data is not available.

Patterns and Biases

This brings us to more biases and pattern matching. We deal with uncertainties by trying to match previous experiences with what we see now and the goals we have to meet. Those goals include keeping a job, keeping students happy, keeping ‘safe’ and keeping our own values intact.

If nothing has gone wrong in the past, then we tend to think that nothing will go wrong in the future. If we start to drift from the standards and nothing goes wrong, then it is harder to justify why the standards are in place, especially if we have been rewarded for the positive outcomes without an accident taking place.

If the diving students have a good time, they feel they’ve learned something and have achieved a positive outcome, then they will likely come back and spend more money in the shop. If they don’t notice ‘quality’ because all dive centres appear to be the same but charge differently, then they will likely go with the cheapest. They are novices and so exemplify the Dunning-Kruger effect - they don’t know what they don’t know, and even worse, they don’t know they don’t know.

What happens when it goes wrong?

Now consider what happens if something goes wrong. There is a closer examination of what happened by those inside and outside of the event. Inside refers to dive centre staff or project staff. Outside refers to social media, lawyers, law enforcement and regulators (e.g., OSHA, Worksafe, or the HSE).

A ‘bad’ investigation would focus on non-compliance and proximal causes and attribute blame for not following the standards or the rules. However, a ‘good’ investigation would look at ‘normal’ work, the context in which the dive centre or instructor is operating, the commercial and time pressures they are under, the quality of the information and guidance they have and how easy it is to access, how the gap between ‘work as imagined’ and ‘work as done’ is normally navigated to prevent accidents/incidents from occurring, and how the capacity to fail safely was eroded on this particular occasion.

You don't need an accident to join the dots!

The key thing is that you can review what 'normal' looks like without having to have an accident. What is needed to support this is a learning organisation, one that wants to look for the adaptations that highlight the gaps between 'Work as Imagined' and 'Work as Done'. What the instructors are doing to manage the risk dynamically when they can't operate inside standards. What the dive centre is doing to deal with ill-prepared clients. What patterns, cues or clues are the experienced divers or instructors using to spot something bad developing and head it off at the pass?

If you do have an adverse event, how are you going to look at the event? From a backwards-looking perspective, joining the dots as you go and falling foul of confirmation bias, or forward-looking from the perspective of the diver/instructor to determine how it made sense and what conditions were present? If error-producing conditions are present, then we should address those before we focus on the errant diver/diving instructor. Addressing the system will improve more than punishing the individual. Learn about Learning from Unintended Outcomes

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a niche company focused on educating and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website.