Diving Deep into Diving Safety: The death of Linnea Mills through a lens of HF and System Safety

Mar 09, 2025Diving is often described as a “safe” sport—relaxing, fun, and open to anyone who can pass a basic training course. Yet this simplicity is deceptive. True safety is not just the absence of accidents and incidents, but the active presence of barriers, defences, and a culture that supports learning from mistakes. As someone who spent 25 years in the Royal Air Force, working in operational, research, trials, and flight instructional roles before moving into the commercial diving arena and completing two MSc degrees in systems thinking, I’ve seen firsthand that incidents are rarely the result of a single “bad apple.” They happen when complex systems—procedures, people, organisational pressures—drift, degrade, and overlap in ways we don’t expect. They are "Normal" as Perrow would describe.

In this blog, we’ll discuss four stories that show how events often arise from systemic pressures rather than the often attributed 'individual negligence'. Then, we’ll explore what diving can learn from other high-risk industries about practical drift, just culture, and the necessity of open debriefing to reduce the likelihood of adverse events and tragedies like Linnea Mills's death.

Diving and System Safety: Setting the Scene

Safety in diving is tricky to define. Many people equate “safe” with “free from harm,” but you can’t really measure that. You can only measure its absence—accidents, fatalities, or near misses. A more useful definition sees safety as the capacity of a system to adapt to real-world challenges. In other words, have we built in enough resilience—through training, equipment design, teamwork, and culture—that when something goes wrong (as it inevitably will), we can recover before disaster strikes?

"Safety is not just the absence of incidents and accidents, but rather the presence of barriers and defences, and the capacity of the system to fail safely."

Todd Conklin

In high-consequence industries—like aviation or healthcare—teams know incidents will happen. The best organisations focus on building defences and learning from every close call or failure through reflection, debriefs and incident investigations. In diving, we frequently rely on the idea that “nothing bad has happened so far, so therefore everything must be safe.” But that’s a dangerous metric to use. We ought to be building a robust culture of discussion, feedback, and practical scenario training that helps divers detect and adapt to the unexpected before it becomes fatal. The goal should be to prepare divers to dive in the real world with all its messiness, not just meet the requirements to pass the course.

Four Stories that Illustrate Systemic Breakdown

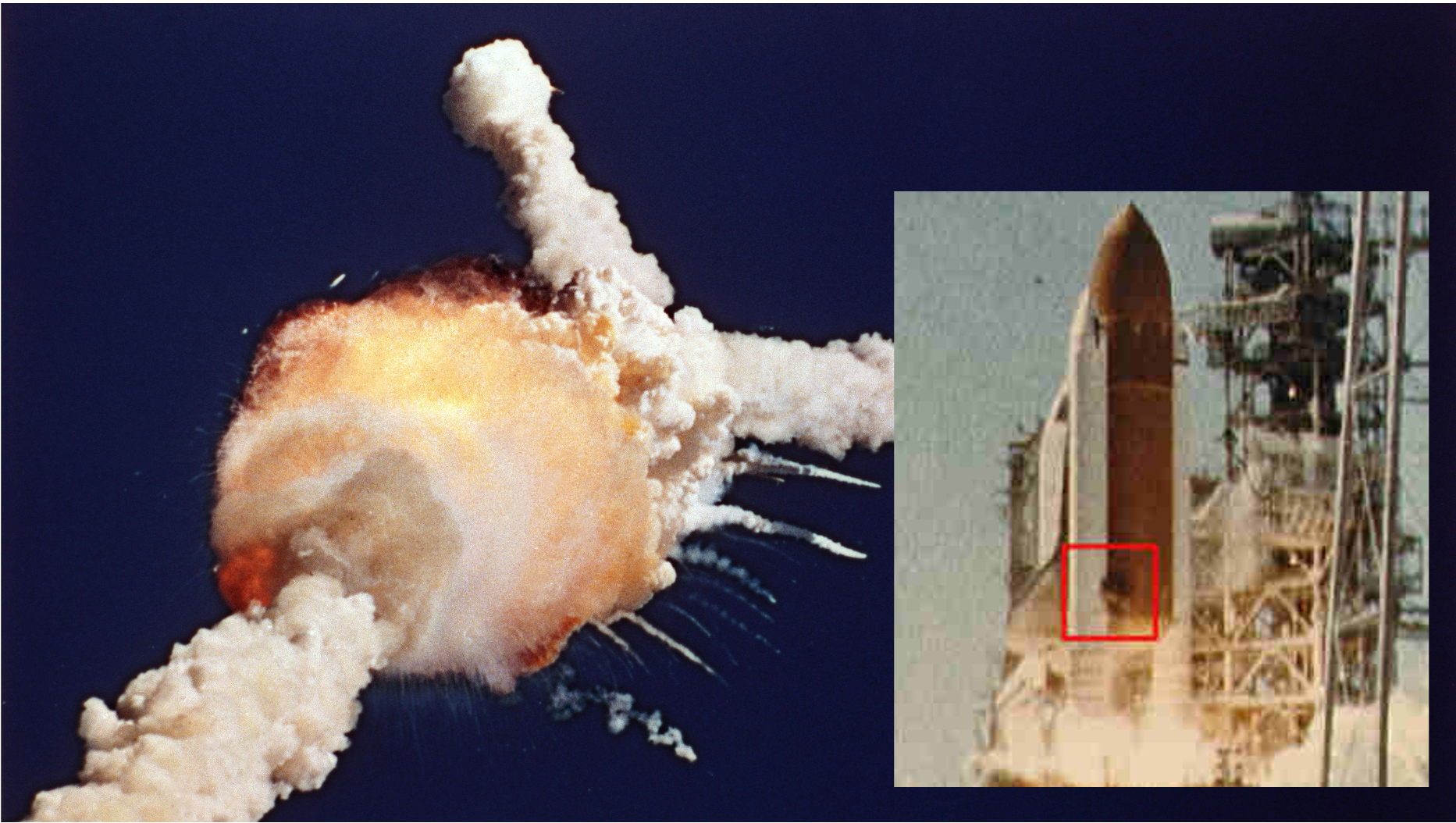

Challenger Disaster

When NASA launched the Challenger in 1986, no single engineer or manager set out to break the rules or make a decision that would lead to the loss of the orbiter and everyone onboard. Over time, small compromises piled up—risk sign-offs that used to read “prove why we should launch” became “prove why we shouldn’t.” The organisation normalised flying with O-rings that showed worrying patterns of damage but hadn’t yet caused catastrophe - the risk had been accepted. Those small deviations from best practice morphed into a routine acceptance of potential harm - the trade-off was against commercial and schedule pressures to deliver a commercial capability. And once that potential loss (risk) was internalised as “normal", and the environmental conditions meant that the o-ring vaporised on launch, 73 seconds after liftoff, the system failed and everyone was lost.

Black Hawk Shootdown

In northern Iraq, two U.S. Air Force F-15C fighter jets accidentally shot down two friendly Black Hawk helicopters, killing everyone on board. All participants were skilled professionals, accustomed to peacekeeping flights where nothing much happened. Unnoticed shortcuts and assumptions had grown comfortable in day-to-day practice: outdated identification photos, communication gaps, and the assumption that “no one else flies here, so anything we see must be hostile.” Multiple small drifts—each of which had never caused a problem and each within the margin that the subunits believed they had to play—suddenly collapsed up and turned a routine day into a fatal shootdown.

'Just a Routine Operation'

In a UK operating theatre, an anesthetist couldn’t intubate or ventilate a patient (Elaine Bromley). Nurses asked if the team needed help, but the doctors insisted they had things under control. Martin Bromley, Elaine’s husband, was an airline pilot. He was stunned to learn that “investigations” in healthcare often ended with “just one of those things,” rather than systematic analysis aimed at finding and addressing deeper issues within the system. This resonates with diving: unless we have structured debriefs, near-miss reporting, open dialogue, and a formal way of looking at adverse events e.g., learning reviews, we can’t truly understand how normal people make normal decisions that unexpectedly (in real time) lead to tragedy. Martin and others have led the change in the healthcare space regarding human factors, leading to the formation of the Clinical Human Factors Group and the Health Service Safety Investigation Branch.

Linnea Mills Diving Fatality

Eighteen-year-old Linnea Mills was participating in an Advanced Open Water class with a new (to her) dry suit. The instructor was relatively inexperienced, time pressures were piling up, and a mismatch in equipment inflator hoses meant Linnea’s new suit couldn’t be inflated. She was also overweighted—45 pounds of lead in a 25-pound lift BCD, plus no way to feed gas into the suit for buoyancy or to control squeeze. Despite the obvious hazards to an experienced eye and the 'after the fact' observer, neither Linnea nor the instructor recognised how dangerous that configuration could be. Unnoticed or unaddressed issues across the system stacked up: limited experience, brand-new suit to Linnea, limited daylight, cold water, minimal time for proper checks, no credible emergency action plan. The result was a fatal outcome that left the dive community reeling but also revealed how widespread these systemic problems could be if people wanted to look.

The submission to the court for this case can be found here.

Practical Drift and the 'Normalisation of Deviance'

“Practical drift” describes the gap between how we should do the job (like the official instructor manual) and how we actually do it under real-world constraints (short on time, new gear, anxious students, suboptimal conditions). Over time, tiny shortcuts, rationalised as “this is fine,” accumulate - normal human behaviour. In space flight, in aviation, and especially in diving, such drifts become normalised until one day the margin for error collapses. Once the system fails—whether by O-ring blowout or an overweighted diver sinking beyond reach—everyone looks back and wonders, “How could this possibly happen?” Unfortunately, NASA didn't learn from the loss of Challenger, and similar organisational failures were at play that led to the loss of the shuttle Columbia - 'History as a cause'.

The Importance of Debriefing and a Just Culture

One of the biggest differences between high-reliability organisations and typical diving operations is the disciplined approach to debriefing and reflection when something adverse or unexpected happens. In some aviation settings, no flight ends without a thorough review—whether it took 10 hours or 10 minutes. Everyone can speak openly about mistakes without fear of punishment. This “just culture” recognises that while negligent or reckless acts deserve accountability, most errors arise from normal people trying to do their jobs in complex systems. If we punish every slip, and social media is very good at this, we drive learning underground. Interestingly, diving takes place in an inherently hazardous environment, and so what does 'reckless' mean in some cases?

A just culture also recognises the emotional toll of incidents. Traumatic events—like a diver’s rapid ascent or a near-drowning—can leave lasting effects on all involved. Good organisations include post-incident support, counseling, or at least some system to ensure that the divers (and instructors) aren’t left to process guilt and sorrow on their own. In the non-diving space, the Restorative Just Culture checklist is a great place to start for identifying who has been harmed, what do they need, and whose obligation is it to address that need. In the diving space, Dr Laura Walton, provides amazing resources and support via www.fittodive.org

Organisational Pressures and Training Gaps

Diving agencies, like many industries, face commercial realities. The push to process certifications, keep customers happy, and increase revenue can overshadow the deeper work needed to ensure that each new diver can recognise and manage real-world hazards. Some agencies allow instructors to “self-certify” for certain specialties. Without robust oversight or mentorship, gaps can develop that no one notices until an accident occurs. This self-certification process goes against the basic premise of organisational oversight, which allows the agencies to remain unregulated.

We see these gaps in feedback loops, too. Most incidents remain hidden—especially close calls that never escalate to major accidents. If we don’t actively encourage divers and professionals to share near misses and mistakes, the broader community misses out on essential lessons. While the want to protect oneself from potential liability is powerful, the cost of silence can be far higher in terms of future tragedies. This external reporting relies on a level of altruism because it is unlikely that YOU would make that same mistake again, but others could learn from your event, and you could learn others' mistakes or successful recoveries.

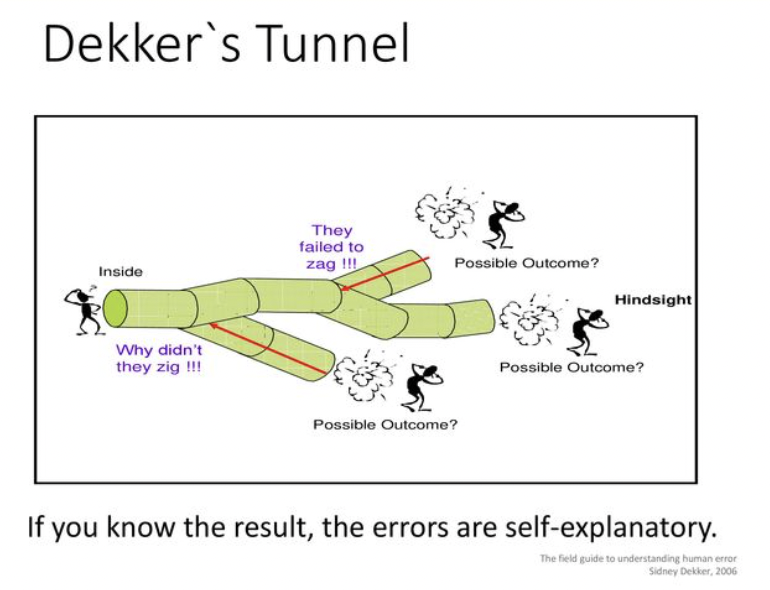

Dekker talks about 'being in the tunnel' where we 'lose situation awareness' at an individual level. This also applies at the organisation and system level too. If we are in the system, it is very hard to identify the gaps. Another way to think about this is a person or operation can only assess their processes by internal logic. Therefore, an external, i.e. "higher" or overarching level, controller or regulator is needed to account for external abnormalities/changes that cannot be addressed at the internal level. This is why internal regulation through bodies like the RSTC and RTC (which are made up of the stakeholders inheriting the standards) have limited effect on creating effective change towards safety as commercial drivers influence their decisions.

Lessons and Building Resilience

Share Stories: Dive culture needs more open dialogue about incidents. Rather than ridiculing or blaming, we should ask, “How did this make sense at the time?” (Research on this applied to diving.)

Encourage Psychological Safety: Instructors and divers who fear consequences (legal or social) stay silent. A culture that welcomes honest conversation allows everyone to learn and improve.(Psychological safety blogs on THD)

Focus on the System, Not Just Individuals: While personal responsibility matters, we also need to ask how the context and social/physical environment—time pressure, equipment mismatch, commercial demands—contributed to the event. ('Context Matters' blogs)

In the real world, procedures can never map out every possibility. True safety is about resilience—anticipating that, eventually, you’ll face an unexpected scenario. Training should prepare divers to adapt and think critically under stress, not just tick boxes on skill checklists. Practicing the things you are good at doesn't help improve those things you aren't good at. Resilience also thrives on transparency: near misses, “small” errors, and times when equipment misconfigurations don’t quite cause a catastrophe should be recognised as golden opportunities to learn.

If you don't think failure is going to happen in your diving, your team, your dive centre, or your organisation, consider the following questions:

- What processes do you have that would trap the errors before they become catastrophic?

- Have you validated them?

- How often do you hear 'bad news'?

- What happened the last time someone challenged the status quo?

- How often (if at all) do you move past 'that was lucky, best not do that again?'

- Do you just focus on the actions/outcomes of events, or look at the conditions and context surrounding the event?

Conclusion

Diving, by its very nature, involves an inherent exposure to many different hazards. We can’t breathe underwater without specialised equipment—and if that equipment (or our decision-making) fails, the consequences can vary from 'meh', to scary, to fatal. However, it’s entirely possible to manage these potential losses through systematic thinking and thereby reduce the likelihood of the event occurring, or being able to fail safely and recover the situation. By shifting from a culture of blaming “bad apples” to one that looks at how normal people make mistakes in complex settings, we can create a community of continuous improvement, ultimately leading to more enjoyable dives and safer exploration.

Our call to action is this: commit to asking deeper questions around local rationality, hold regular debriefs, and share your stories—even the embarrassing ones - you're not likely to be the only one who has been in that situation. The more we normalise discussing faults, the variability in our performance, and the context in which those decisions were made, the greater our collective capacity to dive safely.

Fundamentally, safety isn’t just about preventing accidents; it’s about creating a robust and supportive socio-technical system that embraces learning at every turn, especially across the different silos of training agencies, equipment manufacturers, communities of practices and geographic locations. Just as importantly, it’s about looking out for each other as we explore the depths, aware that we can only master the underwater world by humbly acknowledging how vulnerable we actually are—and by doing everything in our power to keep ourselves and our dive buddies safe.

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver. Along with 12 other instructors, Gareth helps divers and teams improve safety and performance by bringing human factors and just culture into daily practice. Through award-winning online and classroom-based learning programmes we transform how people learn from mistakes, and how they lead, follow and communicate while under pressure. We’ve trained more than 600 people face-to-face and 2500+ online across the globe, and started a movement that encourages curiosity and learning, not judgment and blame.

If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider the first step in developing your knowledge and awareness by taking the Essentials of HF for Divers here website.

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.