The risks we take. The decisions we make. The lessons we MIGHT learn.

Apr 30, 2022The lives we live are full of risks and uncertainties. 'What is a risk?' and 'What is safety/safe?' are particular to us because of the lens we view the world through.

Some might think that cave diving is dangerous, and yet the training (when conducted well and to standards) to undertake cave diving is thorough, giving divers the skills needed to deal with the failures, like the whole team's lights failing, broken guidelines, low/no visibility, out of gas situations, or lost teammates. The statistical risk of a fatality is likely to be pretty small. It is not zero, but it is small. Even 'normal' diving, the risk is in the order of 1:200 000 dives ending up as a fatality.

And therein lies the problem.

Small numbers can lead us to think there isn't an issue. This is because of the way our brains work. Most of the time we make decisions based on biases, heuristics and mental shortcuts. We don't sit down and work out what the numbers mean (even if the data was available), we use things like availability bias, fundamental attribution bias, recency bias, or the sunk-cost fallacy, to make choices and decisions. We don't use System 2 thinking which is slow and methodical, we use System 1 which is fast, efficient and has a low cognitive overhead.

Sometimes we need to slow down. We need to recognise that biases are getting in the way. We need to engage System 2. This blog is all about slowing down. And that slowing down likely saved my life.

June-Dec 2021

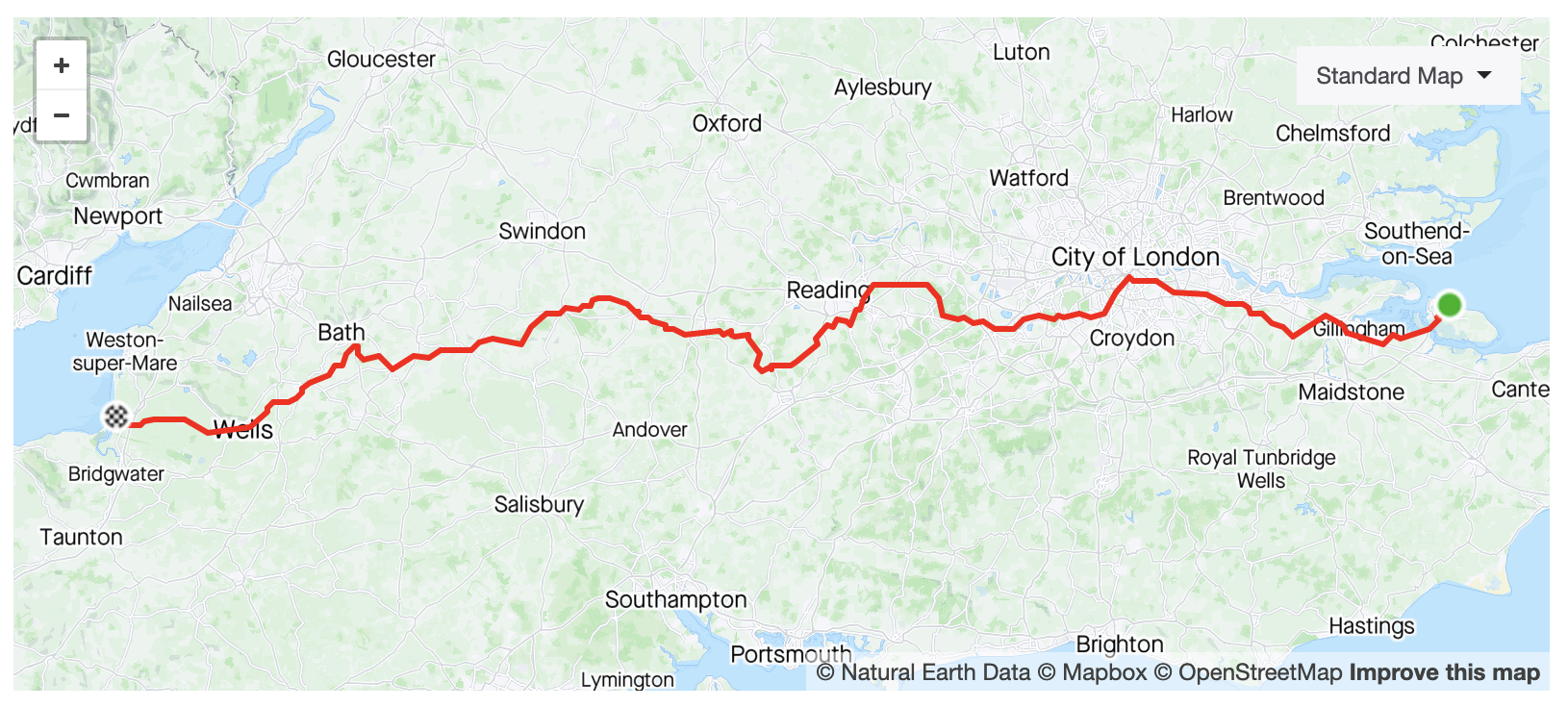

On 20 June 2021, I took part in a solo bike ride which went from Sheerness, on the east coast of the UK to Burnham-on-Sea, on the west. A distance of nearly 360km. This was to be completed between sunrise and sunset. I managed it in 13:30 moving time, at an average speed of 25.6km/h. I felt great.

Unfortunately, I caught COVID in August 2021. It wasn't a major issue, felt a bit rubbish for a few days but that and a number of colds over the next couple of months meant that I didn't get out running or on the bike. I didn't dive either. On 8 Oct, I had a full HSE diving medical, including pulse-oximeter assessment as I'd had COVID, and was given a clean bill of health to go back to diving.

In November, I went over to Calgary to see family and went running three times. All about 5-8 km in length. These were a little harder than normal, but Calgary is at approximately 3500ft above sea level, so the air is thinner than in the UK.

On Christmas Day, I did a 5km run with my dog at a pace of around 6min/km which is slower than normal for me, normally I do a 5km around 5:30/km.

January 2021

During the first couple of weeks in January, the air was colder than normal and when I walked the dog, I started to get some chest discomfort, up in the left shoulder. Nothing major in terms of pain and it dissipated after 5-10 mins when I got home.

I went diving my CCR with Marcus for a photoshoot on 13 January. No issues or discomfort prior to or during the dive.

I went to Sweden in January too, again the air was cold, and again the discomfort was there, and again it dissipated when I stopped. I have an Apple Watch so was monitoring my HR (resting HR 65-70) and the ECG appeared fine. BP was a little higher than normal, but everything appeared ok.

However, on my return to the UK, I decided to speak to my GP. I made an appointment and they gave me an ECG as they suspected angina. The ECG showed an abnormality (inverted t-wave) and so I went to the Emergency Department at the local hospital where I had two more ECGs and blood tests looking for signs of a heart attack (troponin). These were all negative and because I didn't have a history of heart disease, I wasn't hugely overweight (BMI just under 30), didn't have high blood pressure, didn't have diabetes, I was considered low risk and would be treated as a 'routine patient' and put through the Rapid Access Chest Pain Clinic.

I stopped diving. I stopped running. I stopped riding my bike.

February 2021

Due to COVID-induced staff shortages, I was not seen by the RACPC for two weeks. They recognised there was an issue and was recommended for a CT scan. Again, due to high levels of workload and backlogs, this meant that there was going to be a delay in having this scheduled. I was also travelling to the US and Canada, which meant between 18 Mar and 3 Apr, I couldn't get a scan. I rang a week before I left for the US but no slots were available.

April 2021

On 4 April when I returned from the US, I called the radiography department to see when a scan might be available and they booked me in for 19 April. That Friday (8th) I was walking the dog and the chest discomfort came on within 5-10 mins. I was supposed to be flying to the Orkney Islands on the 12th to run a two-day HF class. I didn't want to let the students down but realised that 19th April was 11 days away and things weren't getting any better. The pressures to keep working are a real concern for small business owners - the Human Diver is my full-time job.

I made another appointment with the GP for that afternoon. Another ECG and nothing negative showed up. They spoke with the cardiology department and the consultant rang me back. I was to have my CT scan changed to an angiogram but it might be another 4-6 weeks given their workload. I accepted this because I didn't want to be a burden on the NHS and I also knew that they have been playing catch up since COVID started. There was always 999 if it became a 'real' issue.

The following day, I walked the dog again, and again the discomfort came back. After some more soul searching, I decided to get my wife to take me to the ED. We arrived 16:00, Saturday afternoon, and it was busy. I was triaged and because I was not in pain at rest, I was a lower priority (as I expected). I had another ECG and some more bloods and then saw the consultant at 19:00. He said that again I hadn't reached a threshold within their scoring system (from the tests) for immediate treatment, but after hearing how the symptoms presented themselves, he said there was definitely something that needed looking at and I would be admitted as an inpatient.

The ED on a Saturday night is a busy place. At midnight I spoke to one of the nurses and asked if they were waiting for a bed to come up, and if there was an update from a doctor. At 01:30, one of the registrars came to see me and explained that I had two choices: stay in the ED until a bed came up, or go home. In either case, he would send an email to the cardiac team highlighting his concerns. He explained that even if I got a bed, I wouldn't be seen by anyone from cardiology until Monday. I said that I didn't want to block a bed, I also knew that beds aren't available until someone is discharged and that doesn't normally happen until after lunch, finally, being in a hospital was a greater risk of getting COVID than being at home! I went home at 02:00.

On Monday afternoon I had a call from Cardiac Catheter Lab to say that I was booked in for an angiogram the following day and, if it was needed, I would have stents fitted.

12 April - present

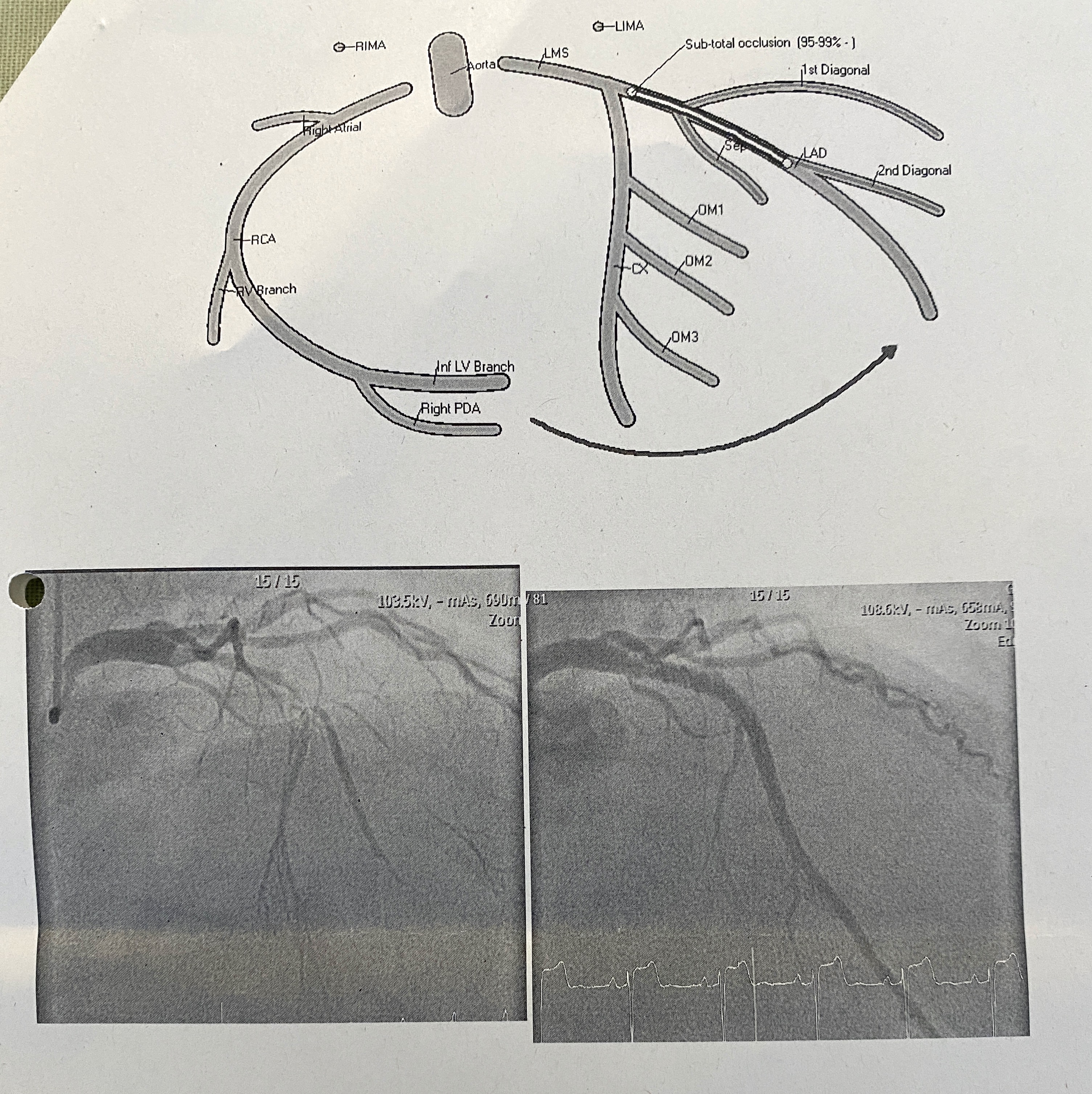

The angiogram went well but they found my Left Anterior Descending (LAD) coronary artery was 95-99% occluded/blocked. They inserted two stents into the artery to open it up and hold it open. All done under a local anaesthetic which is pretty amazing stuff. Three hours later I was out of the theatre with some very painful arms. The left image below is pre-stent with the dye showing the lack of blood flow, the right image is post-stent.

I was kept in the cardiac unit overnight and then discharged the following day. I now have a bunch of drugs to take for the next year plus some others that I will be taking for life.

All of my diving is suspended for up to 12 months and following some advice on the risks of stress on the body, I have sold my JJ-CCR. I will likely get back to underwater photography, something I really miss.

I am now walking 5-10km a day without any issue. I have changed my diet to have less cheese, wine and red meat in it! I have also started a slow-paced walk/run regime to build my base fitness up. Everything appears to be good.

The anti-coagulants combined with the bruising from the catheters being inserted into my arteries produced some impressive bruising! These were between 3 and 7 days post-op.

Some might question why the healthcare system didn't pick this up sooner, or do something beforehand. As with any system that has limited resources, there has to be some way of prioritising tasks (patients). In my case, the tests they ran are recognised as providing high levels of confidence regarding the risks the patient is facing. In my case, the only way to really find out what was going on was to conduct a CT scan or an angiogram. Both take resources and I am not the only patient the NHS has to see. I understood this and I still think the NHS did what they could, given the resources they had/have, and the information presented to them. I am extremely grateful to the registrar who made a strong argument to the cardiology department to get me seen as a priority.

The lessons we MIGHT learn

Students of mine have said to me that the problem with trying to bring human factors into diving is human factors. In fact, it doesn't matter what change is trying to be created, human biases get in the way. Even when we think or believe we should change, the status quo bias gets in the way. The lack of 'evidence' gets in the way. 'Distancing through differencing' gets in the way. (I am different to you, therefore your problem doesn't apply to me. I wouldn't make THAT mistake).

It is one of the reasons I am writing this blog. I cannot make anyone do anything. However, I can influence them to think differently, to think critically, and in some cases, I have been successful.

Things to consider

- Weak signals are present within any system. These are signals which we might think aren't relevant or important but in hindsight they are! Resilience is based on looking out for those weak signals and digger deeper when we detect them. We look to see why it ISN'T a good idea to progress, not convincing ourselves why it IS a good idea to move on. We can easily find excuses to not change the path, to convince ourselves that things are ok. Confirmation bias is the enemy of resilience.

- Weak signals don't just apply to individuals, they apply to organisations too. If you are in a leadership or quality position, what do you hear from incident reports, QC forms, instructor re-evaluations, or social media about the performance and safety of your instructors and dive centres? You cannot measure something as being safe by the absence of dead or injured divers. It is hard to develop trends with small numbers of reported incidents. Speak to people and find out the ground truth. The absence of data relating to a problem doesn't mean that the problem isn't there. Don't be afraid to ask. Great leaders welcome bad news.

- "It is my risk, if I die diving, something I love doing, then that is my problem". WRONG! If you die diving, you will leave family and friends behind, there will be people involved in your rescue/CPR/body recovery and that will create trauma. Don't just think about how easy it is to get off a boat or enter the water on a shore dive if the conditions are marginal, think about having to get back on the boat or back on shore with a casualty. It is very hard work executing a rescue. You might end up seriously injured through a lack of your fitness.

- Your internal detection system can be more effective than technology. I knew that something wasn't quite right even though the ECGs and blood tests didn't show anything. Once I had explained it, the consultant and registrar realised something wasn't quite right. Their experience and resilience played a part in my survival.

- If you believe that something isn't right, have the courage of your convictions to follow through. This is really hard when there is a lot at stake. There are often perceived barriers to being able to speak up. Employment, reputation, money, time, not wanting to cause a problem to others, not wanting to point out the obvious, not wanting to counter the willful blindness that is present. Integrity is doing the right thing, especially when no-one is watching. Internal honesty...

- As humans, we are terrible at looking at what we need to do now to change something in the future. We live in the here and the now. Tomorrow is another day, until tomorrow is today and there are no more tomorrows.

Summary

This blog was written for a number of reasons:

- Diving is inherently hazardous despite how it is marketed. Not all hazards are encountered underwater, they are met on the surface too! However,being on the surface with a cardiac issue is more survivable than being underwater with one!

- A large proportion of the diving community is at an age where health issues will start to surface (pun intended!) and these can be a problem, especially when they go diving.

- Physical fitness doesn't make you immune to the problems we face as we get older. Note, this isn't an excuse to say 'in that case, I'll not get fit'. Being fit helps reduce health risks in general. If you think that the fitness levels asked of the UK DMC post-'simple COVID' for 'satisfactory performance' are too stringent, maybe you need to consider your health and fitness in general.

- Risk is in the eye of the beholder. You don't have to be risk-averse, be risk-aware or risk-savvy, especially when it comes to the cognitive biases faced when making decisions under uncertainty.

- It is hard to speak up when you think you are on your own. Having someone else talk about a similar issue can make it easier for you to speak up.

- I believe in sharing stories of my own performance variability, both in the physical sense and the cognitive sense. I am human. I will err. I am hoping that someone else in a similar situation will learn from this event and we save another diver.

- Lessons are not learned until something has changed and its effects are measured. Lessons that have been learned mean change has happened and change is really hard. Hence, lessons are identified but they might not be learned. Only you can really learn a lesson yourself.

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a niche company focused on educating and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website.

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.