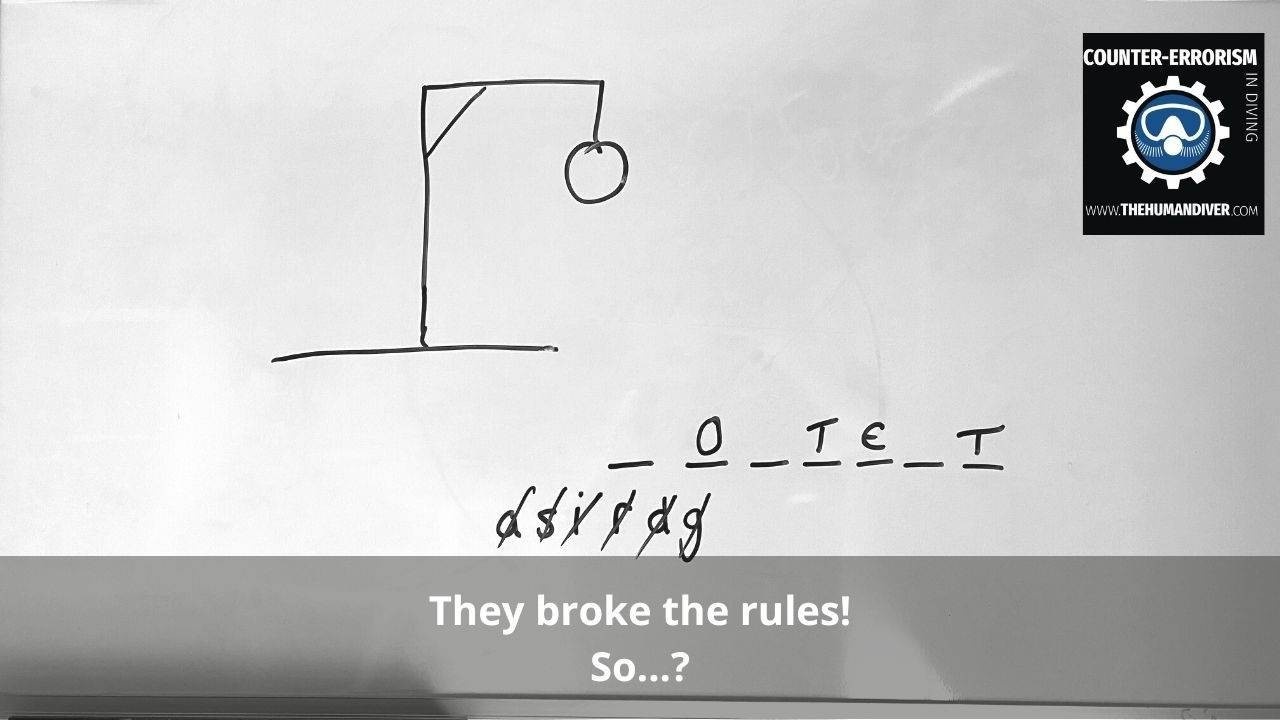

They broke the rules! So...?

When something goes wrong, and there has been a deviation which appears to be a ‘root cause’ of the event, one of the first cries that come out is that they broke the rules, and therefore those involved should be punished because of their behaviour. This cry comes out because the rules are there to be followed, and if they aren’t, accidents will happen in the future. The problem is that things go wrong when the rules are being followed, and they don’t go wrong when they aren’t!

This poses a problem for our brains, especially our socially-focused brains - we like simple solutions, even if they relate to complex problems. Unfortunately, science has shown us that in some cases, our immediate and quick (often emotionally-driven) response is wrong.

What is the Purpose of Rules?

So, what is the purpose of having rules in diving? Normally, they are based on something going wrong in the past like running out gas, getting lost inside a wreck or cave, having your single light fail in a cave and so can’t follow the line, not having direct control of students and them doing something dangerous to themselves, or having an oxygen seizure because of high pO2 in your breathing mix. I am sure you can think of many more.

I believe the rule or standard provides value for five groups of people:

- those who don’t know what they don’t know and so need guidance.

- those who do know but for some reason, they have not remembered/cannot recall.

- those who want to follow a conservative path and want something to refer to.

- those teams who recognise that standards allow mutual accountability to be realised - I can call you out if you miss something, I expect you to call me out if I have missed something.

- for those in authority to ensure that safety and performance is managed to a level that is expected by pointing out what should be done and holding them to account (blame) when the rule is broken.

In diving, there are very few absolute rules, rules that if broken will ALWAYS get you into physical harm, even if they get you into legal harm when no physical harm has occurred. A human factors researcher, Denham Phipps, studied anaesthetists to better understand why anaesthetists broken rules and wrote this paper – ‘Identifying violation-provoking conditions in a healthcare setting’ which I believe has utility in the diving space. (If you want a copy, drop me a message via the contact form at the top).

Violations

A violation is often defined as a deliberate act that deviates from standard protocols or practices, and this is different to a ‘human error’ which is seen as an unintended deviation e.g., a slip, a lapse, or a mistake. However, it might be that the rule or standard prevents normal operations from taking place as they should e.g., the commercial situation means that taking four divers on a Discover SCUBA diver dive with a single instructor when they are supposed to maintain ‘direct’ control of all the divers is the only way to generate enough revenue. Fundamentally, how do you maintain ‘direct control’ if you have two hands and four clients and one of them decides to bolt to the surface?!

Conditions

Returning to Phipp’s paper on violations, the important thing to recognise straight away is the use of ‘provoking conditions’ in the title. Anaesthetists are professionals. They are highly trained. They literally have people’s lives in their hands. They know what should be done, when and why. They are also subject to many operational and environmental conditions that make it harder to follow the rules, especially if they don’t appear to add value to them, to the patient or to the wider organisational goals. Phipps highlighted three key themes associated with conditions which would provoke rule-breaking. I have no doubt that there are many parallels between diving and this environment, although no work has been done in this area as far as I know.

- The Rule. This covered four sub-themes: the credibility of the rule and its source; who owned the rule; how much force could be applied to ensure compliance; and how clear the rule was to the task at hand.

- The Anaesthetist. This theme examined the following three sub-themes: risk perception and acceptance of the anaesthetist; the experience and expertise of the anaesthetist and the team, and the professional or group norm.

- The Organisational or Situational Factors. These conditions were about how and where the operation took place and looked at: time pressures; resource availability and condition; design of equipment; and concurrent task activity.

The paper provides multiple examples taken from interviews with anaesthetists. I have created some similar examples under each of these topics to give you an idea of what these might be as they relate to diving.

The Rule.

- The WRSTC says I must have a snorkel when teaching. However, they get in the way, they don’t add value. I don’t know any other instructors, including Course Directors/ITs who have one with them.

- Are the rules focused on genuine safety or are they about limiting liability for the agency? e.g., we take a folded snorkel in our pockets because the standard says I must, but I have never used one.

- “I have seen rules broken many times (e.g., student ratios) but nothing is done to address the problem by the agency.” therefore why should I follow them?

- “How would the agency know I broke the rules? All they care about is the number of certs I issue in a year.”

- “The instructor guide is ambiguous. It says I can do a Controlled Emergency Swimming Ascent (CESA) as a single instructor but how do I manage the other divers? I can’t go back and forth to the shore to pick them up one at a time because there isn’t enough time and the students would get cold too. My Course Director told me it was up to me whether I left them on the surface or the bottom when I did this skill development during my IDC.”

The research shows that most engineering-based organisations believe that safety is best achieved through following rules and processes, and expected behaviours. However, because of our unique ability to adapt our actions to suit the local conditions and demands, safety in a dynamic and uncertain environment can be maintained because workers do not explicitly follow the rules or processes. Instead, they interpret the rules and standards, adapting their resources to maximise effect, developing workarounds, and inventing in situ many of the routines that ultimately come to make up the procedures that are used by the organisation. Many organisations possess an illusion of safety because they believe these rules will be followed and this creates safety - an exception to this is pilot training where pilots are routinely trained to question the validity of the protocols that they have to follow and or break (Silbey, 2009).

The Diver

These three all relate to how the diver/instructor perceives the risk and what their level of risk tolerance is. There is a paradox here. The more experienced we are, the more we subconsciously see as a threat, at the same time, we spend less time undertaking active engagement with the task or environment because we know what to do. Some call this complacency (when something goes wrong), but when it goes right, we call it efficiency when the same actions go right!

- “I did a blind jump in that cave because I knew it and I’d been there before.”

- “I didn’t analyse the gas because I saw them connect the fill whip and fill the cylinder in front of me."

- “The minimum gas to start the ascent was 80 bar but we wanted to explore a little more of the wreck and ate into our margins. We knew that was the case, but we accepted it because we weren’t coming back here again and the reward was certainly worth it when you see the photos we took.”

The Organisational or Situational Factors

- “To do a comprehensive pre-dive brief which should involve a check of understanding takes too long, and so we use closed questions to end it and people can get ready. They’re just following us, so it is ok.”

- “Gas switches should be done face to face at the same depth. However, the current was so strong, that there was no way we could do that, so we stacked on top of each other and authorised the switches from above having checked the depth, and MOD on the cylinder."

- “The dive centre is struggling, and we have to maximise the number of students going through. This means that dives are shorter than we’d like and because there isn’t a clear definition of ‘mastery’, then we can sign them off when they’ve done the skills once or twice. The students have had a good time, so they don’t know, but feel good.”

Context and Conditions

As you can see, these themes don’t necessarily exist in isolation and there is some overlap between them. This is to be expected given the variety of how instructors are developed, how they currently teach, the operational and social environment they are in, the agencies they teach for, and the students they teach. The key thing to recognise is that themes are part of the conditions, the context, in which diving is taking place.

Context is something we rarely look at when it comes to learning from unintended outcomes because it is hard to do, and it requires a Just Culture to expose the deviations that makeup ‘normal’. Proximal causes are easy to spot, and latent issues like those conditions identified above, are not so. Yet it is the conditions that drive behaviours. Accident investigations and follow-ups should look at the 'extent of conditions' - how prevalent are these conditions in your operations?

The Social Acceptance of Deviation

This brings me to the final part of this blog and it is a lead-in for a much longer piece I am writing on the ‘Normalisation of Deviance”. The term "Normalisation of Deviance" came from the work of Diane Vaughan following the loss of Challenger in 1986. Contrary to popular media, the 'Normalisation of Deviance' is not about the continued breaking of rules or standards, it is the social acceptance that risks being taken are socially accepted and therefore the behaviour is not considered deviant.

“In 1992, after six years analyzing the history of launch decision making in the years before the Challenger launch, I had found no evidence of rule violation and misconduct by individuals. Instead, the key to accepting risk in the past was what I called “the normalization of deviance”… The normalization of deviance was a product of NASA’s organizational system: the connection between environment, organization, and individual interpretation, meaning, and action… launch. The decision was not explained by amoral, calculating managers who violated rules in pursuit of organizational goals, but was a mistake based on conformity—conformity to cultural beliefs, organizational rules and norms, and NASA’s bureaucratic, political, and technical culture.”

Deviance is a social construct, not a technical one. That means the baselines we set and the deviations we take are part of the social and cultural aspects of our diving – we don’t believe we are doing something unsafe otherwise our peers would say something - this includes agencies acting 'unsafely' too! To understand how deviation happens, we have to take a bigger look at things and see how it has become socially acceptable to undertake certain activities which others would consider unsafe. This social construction will be the point of the longer blog which will be published soon.

Summary

Accidents happen as deviations from normal, not necessarily deviations from the rules. The rules might be the norm, but there is no way the rules can match the reality and so there are always gaps between ‘Work as Imagined’ (rules, process, procedures, standards etc) and ‘Work as Done’ (what really happens given the goals, conflicts and constraints faced).

If you want to reduce the prevalence of rule-breaking, look to understand why the rules are being broken, i.e., the social, technical, and cultural conditions in which the operations are taking place. Move from focusing on the individual to the wider system, because the current system is broken. There are potentially a large number of divers who have never had the reasons behind rules explained. As such, they break rules they don’t know exist.

A Just Culture is about supporting the ability to tell context-rich stories about how it made sense to do what you did, even if that meant breaking the rules.

Importantly, punishing someone (via disciplinary means or via social media) without understanding the context is unlikely to make a difference to others’ behaviours if the conditions surrounding the diving haven’t changed e.g., time pressures, inadequate standards checking, fast progress through instructor training, lack of psychological safety… Saying that punishing someone sets an example so others won’t deviate is a fallacy because if the reward is greater than the risk of getting caught and the subsequent punishment, the rule will continue to be broken.

Address the system, not ‘fix’ the individual.

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a niche company focused on educating and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website.