What does safe mean? How would you measure safety in diving?

Apr 09, 2023When you go diving, do you even consider what ‘safe’ means? ‘Safe’ can mean many things to many different people. A 10m reef dive for some has a level of risk, maybe from the wildlife that resides there or the currents or waves that are present. A 30m wreck dive with some level of penetration has a level of risk, maybe very low visibility, or the risk of structural collapse thereby trapping the divers or being lost inside without a line and running out of gas. A cave dive has a level of risk, lost line, poor visibility, and running out of gas. The perception and acceptance of risk is critical when considering 'safe'.

The acceptable level of risk is down to each of us, at the time, given our training, skills, and knowledge. What about when we have no experience? When we are a novice, we have no concept of what an acceptable level of risk is. We’d like to think it will be close to zero, and we will believe that the instructor and/or dive centre is managing the risk for us. And besides, if anything goes wrong, we’ve got insurance to (re)cover the situation (and if you are in the US, you can likely sue someone!)

But what does ‘safe’ look like in reality?

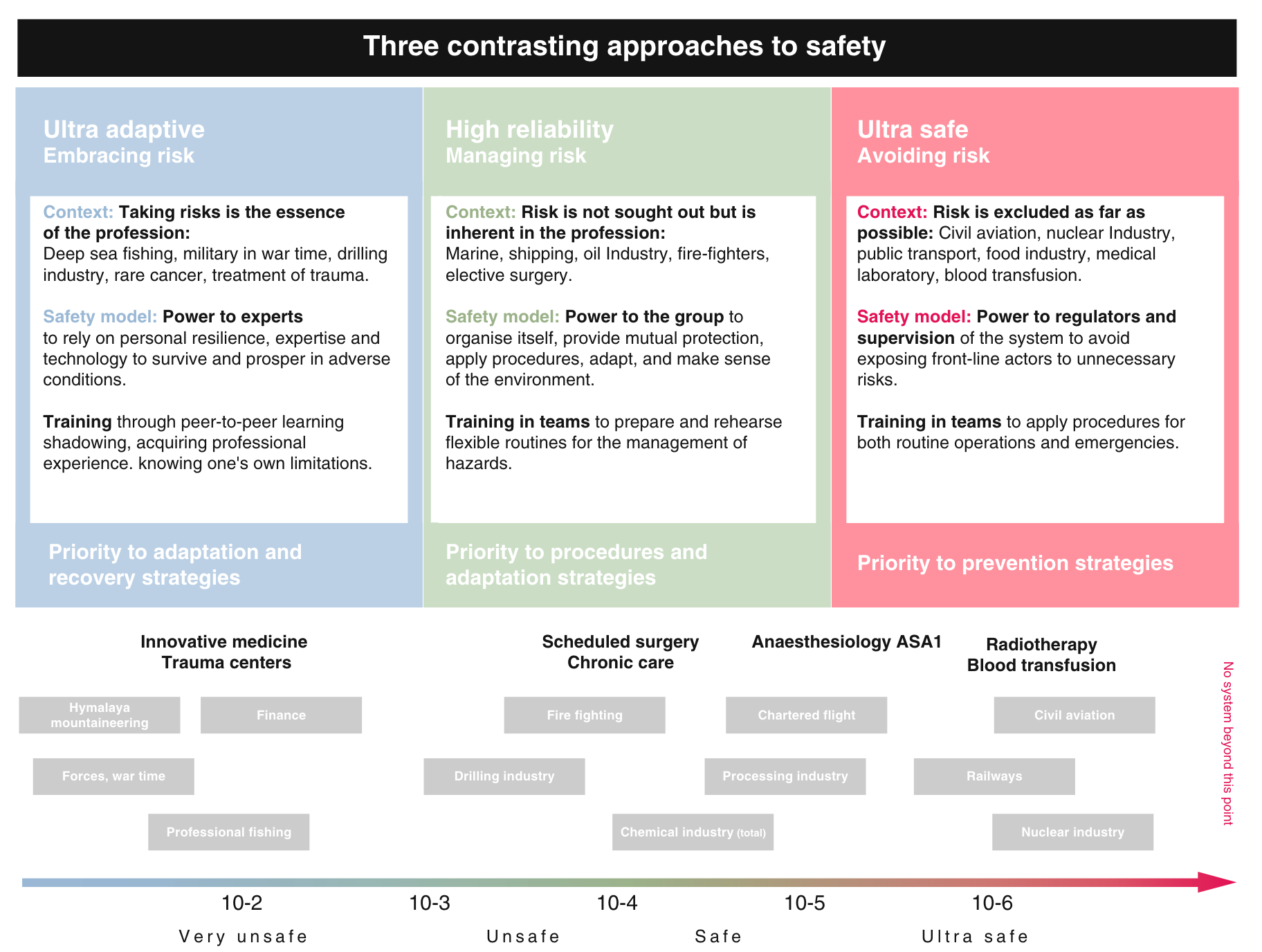

This framework from a publication on safety in healthcare highlights that there are different perspectives present when considering how to approach the risks faced. We can see that the different domains have different levels of acceptable risk along with different types of healthcare activity:

- Ultra Adaptive. This is where teams and organisations embrace risk because they know that they cannot control the context in which they operate.

- High Reliability. This is where the focus is on risk management because there is an inherent risk that should be 'controlled' through processes and procedures.

- Ultra Safe. This is where the consequences of failure are huge and so need to be avoided by massive investment.

Where does the world of diving sit? You might say that it sits in the Ultra Adaptive space, but does the industry behave like that in terms of risk management strategies and practices? The numbers along the bottom refer to catastrophic failures over a certain period. The problem we have in diving is that we don’t have good numbers relating to the risk involved. We have a fairly rough idea of fatalities per year at a global level (at least 180), but we have no idea about the number of dives that take place, nor do we know how many active divers there are. So, what is the failure rate for diving? The often quoted number is 1:200 000 (fatalities per dive) but I have yet to find the original source data for this.

Diving safety is often measured by the number of fatalities that happen. The issue with this metric is that it contains so many contributory variables. When the numbers go up or down, it can be claimed to be down to some ‘intervention’, but, given the number of variables, it is unlikely to be down to one ‘intervention’. The same as saying DCS can be managed effectively by changing a GF value, forgetting the numerous other physiological and environmental factors.

Would we consider a ‘safe’ dive one in which everyone gets back on the boat/shore, having had a dive that didn’t end up with anyone being physically or psychologically harmed, and the equipment being in the configuration it was supposed to be i.e., no ‘out of gas’ situations, or gear dumped or damaged because of an emergency?

Should we consider ‘safe’ being the way in which the dive is conducted so that if an adverse event occurs, then the team are able to fail safely?

How often do you validate your emergency or rescue plans? How often do you practice out-of-gas ascents from depth at the planned rate of ascent which matches your gas planning? When was the last time you practised trying to get a casualty back on your boat in poor weather? When was the last time you practised a lost buddy drill on an open water dive (or a cave dive for that matter)? At a simple level, when was the last time you practised dropping your weights on the surface? How often do you run a debrief to find out where things aren’t working and need to be addressed?

Many organisations have risk assessments as a way of showing how they manage risk. These risk assessments should be used to put processes and tools in place to minimise the likelihood of an adverse outcome. However, in some cases, these are just ‘fantasy documents’ that bear very little resemblance to what happens in a diver training programme because the assumptions made in the risk assessment have not been validated. And in most cases, it doesn’t matter, because nothing goes wrong, and the flaws in the system are not exposed. While it doesn’t matter for THAT time, it sets the team/instructor up for failure in the future because they are creating a false sense of security that the paperwork matches reality and they are covering the risks that might be realised.

Each one of us will have an idea of what ‘safe’ means and how it could be measured. I’d like to ask you to pause and think about what ‘safety’ and ‘safe’ means in the context of your diving. There is always going to be inherent risk in the activity we love – we are in a non-life-sustaining environment after all – and the reward is often worth the risk. We get to see and experience things that many others don’t. At the same time, we have to understand that it doesn’t take much to move from a lovely enjoyable dive to something which is terrifying like being stuck in a wreck in zero visibility and having no idea which way is out.

What do you do to create a ‘safe’ dive? How do you know a dive was 'safe'? Don't fall foul of the outcome or severity biases when you reflect on the dive though...

Fundamentally, we have an individually constructed view of 'safe'. We also have a socially constructed view of 'safe' based on our interactions with others. Problems can happen when there is a mismatch between an individually-constructed view of 'safe' and the team's construct of 'safe', and there isn't a psychologically-safe environment to ask the question - how do we deal with things going wrong?

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a niche company focused on educating and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website.

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.