Why diving incident stories are ‘good’ and ‘bad’

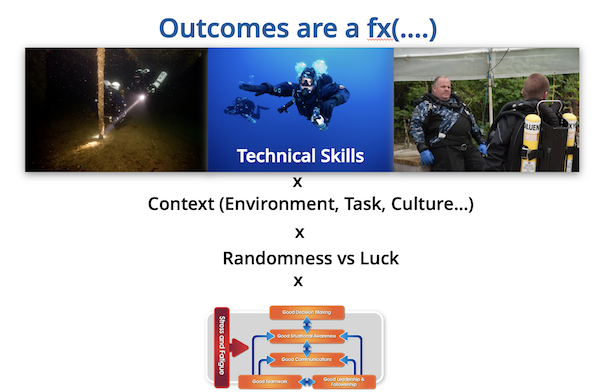

Jan 08, 2023A formulaic approach to diver training helps students pass a class, but does it help a student dive in the real world where there are uncertainties and unknowns? The problem of knowledge transfer i.e., genuine education, is not just limited to diving but exists in many domains. How do you take the tacit (hidden) knowledge that is in an experienced diver’s or instructor’s head and share it with others in a manner which is timely (because of short course delivery times) and consistent (for standardisation reasons)? We can’t, is the simple answer, and this blog will explain why we can accelerate some of the learning through the discussion of incidents, near-misses, and close calls, but there are limits.

Learning used to be achieved through apprenticeships, mentorships and ‘learning on the job’. The goal was to help develop individuals and teams to understand what might happen, how to better predict it, and what to do when the proverbial hits the fan, by exposing them to multiple scenarios where things went well (and wrong), and so build a repertoire of ‘case studies’ to use in the future. The problem is that this process takes time, and the modern societal expectations of rapid results mean that learning is limited, especially if training is focused on technical skills acquisition rather than developing ‘competency’ to achieve successful outcomes in an uncertain environment.

‘Competency’ was purposely used because it sits in the middle of a model from a researcher called Dreyfus. His premise was that competence moved through five stages:

- Novices. Novices act on the basis of context-independent elements and rules. They learn these rules independent of an activity and they (should) apply in all circumstances. Rules are important for novices so that a solid foundation is built. However, they can become a barrier to learning when they get in the way of adaptation, especially as novices often judge success as how well they followed the rules.

- Advanced Beginners. Advanced beginners also use situational elements, which they have learned to identify and interpret on the basis of their own experience from similar situations. They start to use context to discriminate between circumstances rather than the ‘one rule fits all’. The use of ‘mastery’ at this stage of diving is a massive misuse of the word (especially as it isn’t defined).

- Competent Performers. Competent performers use goals and a plan to inform their future actions because the number of rules and options that need to be considered becomes overwhelming. This example from Flyvberg relating to nurses being trained by a senior nurse highlights this problem.

"I give instructions to the new graduate, very detailed and explicit instructions... When I would say this to them, they would do exactly what I told them to do, no matter what else was going on... They couldn’t choose one to leave out. They couldn’t choose which one was the most important... They couldn’t do for one baby the things that were most important, and leave the things that weren’t as important until later on... If I said, you have to do these eight things... they did those things, and they didn’t care if their other kid was screaming its head off. When they did realize, they would be like a mule between two piles of hay"

How many times have you seen something like this with a new Divemaster or Instructor? The task is more important than the context. Goals and plans provide a structure by which lots of both context-dependent and context-independent information can be stored and then accessed. Competent performers use interpretation and judgement to get to their final decision point – sometimes this appears to be lacking when an adverse event is viewed with hindsight. - Proficient Performers. Proficient performers identify problems, goals, and plans intuitively from their own experientially based perspective. The intuitive decision is validated through ‘what ifs’ prior to execution. These ‘whats if’ come from previous experiences and ‘case studies’. Most of the time these are correct because a large number of experiences has been encountered. Furthermore, decisions are not taken in a linear, discrete, step-wise process, but rather they start to ‘flow’ based on the developing situation.

- Experts. Experts do what ‘works’. There is often very little conscious thought applied, and their behaviour is intuitive, reflecting on many, many factors and potential scenarios. Experts do not see problems as one thing and solutions as another, they just ‘do’. Fundamentally, their skills and knowledge have become embodied within them, and this poses a problem when they come to teach someone else – they don’t know what they know!

If you look back over these definitions which have been summarised from Flyvberg’s book on social science, try to work out what diver training delivers as graduates from courses?

You might say that the purpose of a course is to give people a ‘licence’ to go and practice and yet there is a strong position from the industry that you should only dive to the experience of your training. So how do you learn?

Research has shown that for learning to happen, three conditions are needed:

- enough frequent opportunities to experience and reflect so that memories are not lost but reinforced,

- similar situations to those that would be encountered for real, this allows generalisations to be made and experience is then used to fill the gaps, and

- sufficient opportunity to verify the right lessons have been learned before they have been forgotten.

All these need to happen well before the knowledge and skills must be used for real. In an activity like diving, where time is often limited and the weather/visibility isn’t necessarily conducive to diving, this is not easy, and so competency fades. Unfortunately, there isn’t an established learning culture in the diving domain which could help overcome some of this.

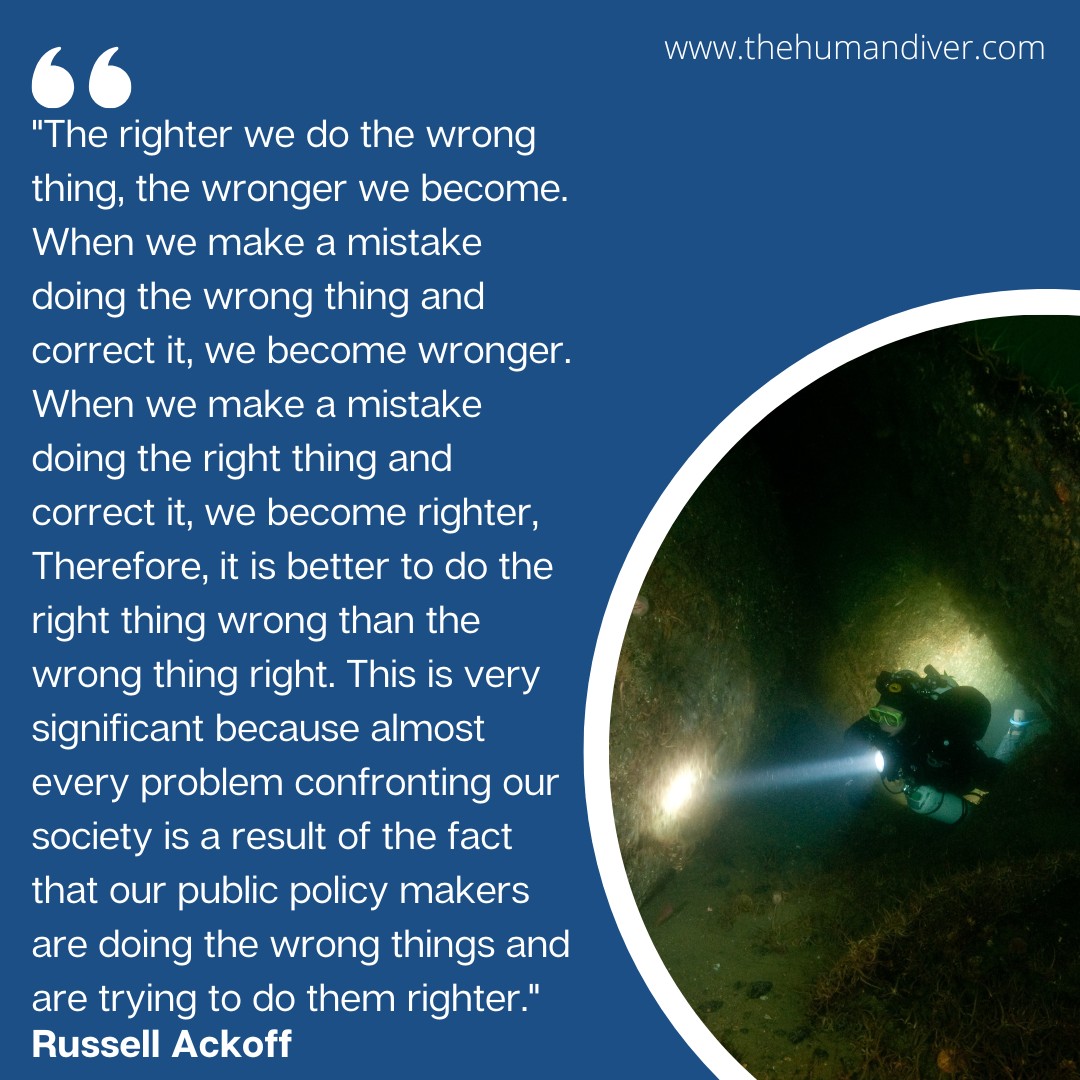

The three points above can be summed up by a great quote from Ackoff which highlights the importance of honest and critical debriefs.

Case studies, near misses and incident reports can help fill the gap for learning, but only if they contain a rich context because it is the context that allows people to move from Advanced Beginner to Competent. This transition happens because the ‘students’ can identify the differences between ‘what should happen’ and ‘what is happening’ and how to resolve it.

Experience from the Essentials programme and the 'If Only…' workshops have shown that when only a short narrative is given (as in many cases in diving), then the lessons identified are often wrong. In this context, the bias of ‘distancing through differencing’ means it is easy to say that we wouldn’t make that mistake (outcome) because we are different. As we add more context, then we start to draw more parallels with our own activities, especially if we are looking for error-producing conditions. Those telling the story must make it ‘personal’ to bridge this gap, otherwise we could end up with something called the ‘backfire effect’ where no matter how much data we provide, the original position will not be changed. This great cartoon from The Oatmeal covers this bias in way more detail than I can!

The practical (social) problem with case studies is that they require a Just Culture to capture and analyse, and a psychologically-safe environment to discuss them. In this context, social media is a double-edged sword. It allows stories to be shared with thousands of people, but it also allows the uninformed, ignorant, or just downright rude, to throw metaphorical rocks at those brave enough to share their stories for the benefit of learning. Case studies also need a framework and some knowledge on how to tell a good ‘second story’ so that the context is captured. That is what the LFUO course is planned to help with, and my MSc thesis will be focusing on the telling of ‘second stories’ following unintended outcomes in diving.

Dave Snowden covers the problem of transferring knowledge here. “We only know what we know when we need to know it. Human knowledge is deeply contextual, it is triggered by circumstance. In understanding what people know, we have to recreate the context of their knowing if we are to ask a meaningful question or enable knowledge use.” This is the whole premise of local rationality – how does/did it make sense for someone to do what they did? Note this is THEM not YOU. Unfortunately, in some cases, those involved don’t know either and it isn’t until an informed discussion takes place that we can unpick some of these factors and their relevance. And then we must capture or document it, analyse it, and then produce something so that others can learn – a learning product of some sort. Those involved in an event must really want to share it with others for that an incident report/case study to make the light of day!

On reflection

Going back to the point at the start, the diver training system is based around a limited transfer of knowledge for several reasons, and as such, we can only really become competent in diving through experience and reflective feedback after these courses. We can accelerate that learning by exposing divers to stories and narratives which look at not just the activity (success or failure) but also the context surrounding it. Rules can only get us so far when it comes to improvement, in fact, they can hinder development because a rule cannot be applicable in every circumstance, and it is the context that determines how to take the knowledge from one scenario to another. When those context-rich stories are told, look for similarities to your own diving, not differences. People are people when it comes to HF and behaviours, it is only the stories that change.

Learn from your mistakes. Better still, learn from the mistakes of others. We don’t have time to make them all ourselves.

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a niche company focused on educating and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.