You can’t risk assess a hazard you don’t know about: DeltaP

Apr 05, 2025Life is full of hazards, those things (threats) that can harm or kill you, and we use experience, processes, and rules to identify the threat, control the harm that can come from the hazard, and/or mitigate the effects if the barriers fail and we encounter the threat.

Drowning is a hazard we constantly face in diving. To control and mitigate this hazard, we have:

- equipment that maintains an airway (regulator and mask),

- buoyancy control (BCD/wing) so we can always end up on the surface even if we run out of gas,

- an SPG to monitor the remaining gas available,

- a team member that we can share gas with, and

- planning and training that deals with gas consumption rates depending on depth and workload, so we enter the water with enough gas based on the plan and monitor the pressure, so we know when to end the dive.

There are other hazards in diving that are a little bit more abstract, e.g., decompression sickness. This is slightly abstract because of the physiological variabilities between divers and between dives (we don’t always respond the same way to descent/ascent profiles or breathing mixes) and the effects on our body (mild to severe for the same exposure). We use equipment (diving computers/rebreather controllers) and gas mixes/decompression profiles to help us manage this hazard. We tend to trust this technology even if we don’t understand the physiological mechanics going on behind the scenes.

“Plan the dive, dive the plan…” (although I don't like this phrase, it does summarise much of the risk management that goes on in diving).

And yet more hazards exist but we don’t know about them.

We don’t know about them because they haven’t been part of our experiences in life, either from the diver training we’ve received, or have not experienced them in person or vicariously through storytelling or incident reporting inside or outside of diving. If we haven’t heard about the hazards, how do we know they exist?

We don’t manage risks in diving, we manage uncertainties, and these are managed through biases and heuristics.

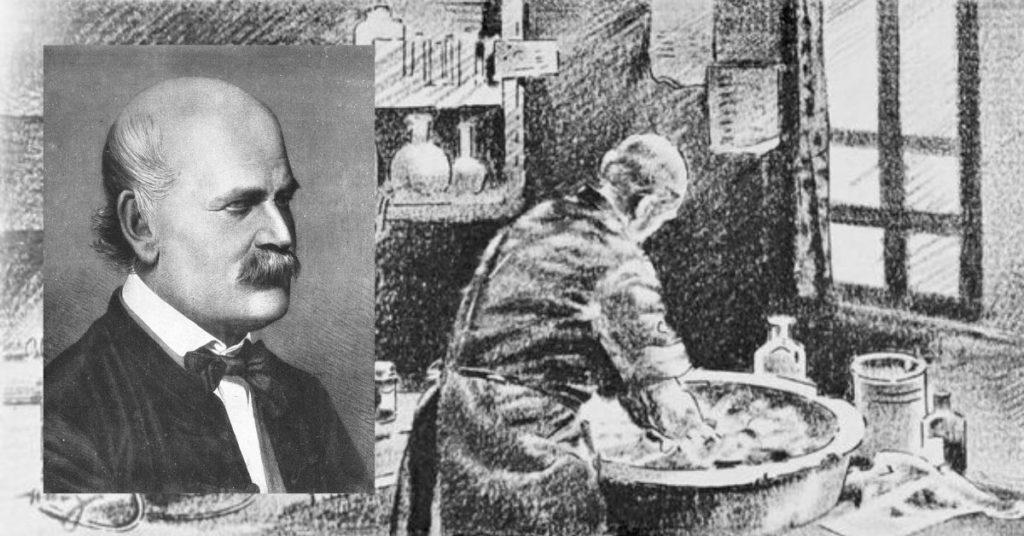

Wash your hands after dealing with a cadaver?! Good idea?!

To show how the informed might think a hazard is obvious, let’s look at an example of deaths in a hospital in the 1800s. Ignaz Semmelweis, a doctor at the time was studying the deaths of young mothers in a labour ward, and recognised that something wasn’t right. The doctor-led ward had a much higher mortality rate than the ward run by midwives. What he noticed was that the doctors would be undertaking post-mortems and then coming into the labour ward to help deliver babies.

Semmelweis hypothesised that the doctors were bringing something from their post-mortems into the labour ward on their filthy surgical gowns and equipment, whereas the midwives were only in the labour ward and washed their hands when dealing with their patients. He suggested that the doctors should change their clothes, wash their equipment and hands, but he was dismissed as being irrelevant, especially as he was questioning the societal upstanding position of doctors. This was even though evidence showed that washing hands in a chlorinated solution reduced mortality from 18% to 2%! It wasn’t until after his tragic death in 1865, likely from sepsis caused by beatings he received in the asylum, that germ theory was really recognised, following the work of Pasteur.

Now, infection control is a critical activity that needs to be managed in healthcare systems.

Differential Pressure, or Delta P.

For those reading this who have a background in commercial diving, fluid mechanics or engineering, you will read the following sections and wonder how those involved could not spot the hazard. A hazard that is so ‘obvious’ it is recognised as critical in the commercial diving space because so many lives have been lost.

Differential pressure, or Delta P, in the diving context is where you have a flow of liquid from a high-pressure location to a low-pressure location, and this can trap people or equipment. The higher pressure could be due to

- potential energy, e.g., a dam with gates to control flow from high to low elevations, or canal lock gates,

- mechanical energy, e.g., intakes on a ship starting up and drawing seawater in, or

- a massive shift in gas/liquid pressure, e.g., a gate or valve opening in a pressurised system.

The hazard is that the diver is drawn by the fluid to the hole or aperture and is jammed against the surface and cannot move until the pressure differential is removed. The diver may drown as their gas supply/equipment is forcibly removed by the water flow, they could be traumatically injured as parts of their body make it through the hole but other parts don’t, or they are stuck in the location and their finite gas supply runs out.

This video shows a toy diver going through a pipeline cut and demonstrates the effect in action.

There are many methods to control and mitigate the different hazards through identification, system testing, lock-out-tag-out (plus many more than I know of!). Using surface supplied dive equipment (SSDE) can be used to mitigate a finite gas supply available from SCUBA equipment.

Why should I care about this?

The problem is that within the recreational (sports) diving training programmes that cover recreational, technical, and cave diving, the hazard of DeltaP is not covered anywhere. The reason? The hazard should not be encountered. If you don’t know about the hazard, you can’t risk manage it.

Two recent examples highlight the need to get this message out there and show that DeltaP is a real threat, and more should be done to raise awareness at both the diver level and the organisation/organiser level.

Brooks, Alberta, Canada

On October 19, 2022, Terrance Ferner tragically lost his life while diving at a reservoir dam operated by the Eastern Irrigation District (EID) near Brooks, Alberta. Though well-intentioned, his dive was carried out without a full understanding of the hazards involved, by him or by those managing the site.

Mr. Ferner, a known recreational diver but not commercially certified, had been asked to inspect gates at the base of the reservoir. Water had been leaking through, causing damage downstream, despite the gates being shut. EID staff believed the gates were closed and safe, based on actuator readings and limited visual checks, but no flow or pressure tests were carried out before the dive.

Unseen by those on the surface, Gate #3 had malfunctioned. It had “over-travelled” during closure, leaving a narrow gap above the gate top. This created the situation where water flowed at high velocity toward the opening. Once Mr. Ferner entered that zone, the force overwhelmed him, trapping his body and causing fatal injuries. The staff on the surface could not do anything due to the pressures involved. His body was not recovered until two days later, when the emergency services had built a berm downstream to equalise the pressure between the reservoir and the stream.

EID had no policies, training, or procedures in place for diving operations. Crucially, no formal risk assessment was conducted. Multiple managers were aware a dive might happen, and some even raised concerns about qualifications, but no follow-up occurred. The organisation’s safety coordinator was not informed at all.

This wasn’t negligence in the traditional sense—it was a tragic case of not knowing what needed to be known. When organisations and individuals operate outside their expertise, hazards remain invisible. Without subject matter knowledge, a risk assessment becomes an exercise in false confidence.

Following the incident, EID imposed a strict no-diving policy unless overseen by an engineer who assumes all safety responsibilities. Training and gate repairs have also been implemented.

2025, UK

“In this video, I take on a unique scuba diving mission: investigating why a [canal] lock gate was refusing to open! We had been trapped on the river [in a canal boat] for 3 1/2 months and needed to find the problem. What I discovered was a real surprise! I dove down 4 meters into the murky depths of the lock. The visibility went from zero to pitch black – I couldn't see a thing! I had to rely entirely on touch, feeling around in the dark until I finally located the culprit: a large piece of wood jammed at the very bottom, preventing the gate from moving. Watch as I retrieve the log and free the lock, allowing boats to pass through once again! This dive was a real challenge, testing my skills in zero visibility. Check it out to see how it all unfolded!”

This diver described themselves as a SCUBA diving instructor and had risk-assessed the situation. He does emphasise that not everyone should do this. This is a commercial diving activity, not a sports diving one, so this diver should not be undertaking the activity.

For those who understand DeltaP, it gets quite stressful when you realise that the water is still running through the lock gates and the diver is right next to the gap. To provide a measure of ‘safety’, the diver is holding a single polypropylene rope in their right hand. Unfortunately, this is no more than ‘safety theatre’ and would not provide an effective means to rescue the diver if they became trapped.

There are two interesting things for me that come from these videos, and they aren’t related to the diver undertaking this clearance dive. I am not surprised about them doing this because I can pretty much guarantee that the diver and the others involved knew nothing about DeltaP, and they are being locally rational; it made sense to them at the time to do what they did. Although ignorance is not an excuse in a commercial setting, in an informal setting like this, it can play a major part. They were incompetent and unaware.

- The first interesting thing is that the comments below the first video are split into two main camps: those who are praising the diver for using their skills to open up the canal and so help others navigate the canal, and those who understand the potential harm that such a diving operation could lead to.

- The second is the subsequent video which was released a month later titled “We got into so much trouble.” where the diver still doesn’t recognise the potential severity of the situation, and the use of language ‘trouble’ infers that what they did was right, but they got caught.

This lack of knowledge is why the cave community puts these signs up at the start of caves to maximise the likelihood that untrained divers do not enter a situation they are not trained for, especially when caverns turn into caves. It doesn’t stop them all, but it does reduce the numbers. The risk culture in cave diving is quite different to the general recreational diving community, too, and so there is external ‘control’ of the hazards faced in the cave diving environment.

Bottom line about hazard assessment

If you don’t understand the hazard, you can’t assess the risk. And if you can’t assess the risk, you’re just hoping nothing goes wrong. And when you are lucky, everything works out okay, and you don’t reflect on the activity, you think you were good and go on to repeat the same activity. This is what the normalisation of risk is all about…

Some external links to help with DeltaP.

Differential pressure hazards in diving - Diving Information Sheet No. 13

Delta P ADCI Checklist

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver. Along with 12 other instructors, Gareth helps divers and teams improve safety and performance by bringing human factors and just culture into daily practice, so they can be better than yesterday. Through award-winning online and classroom-based learning programmes, we transform how people learn from mistakes, and how they lead, follow and communicate while under pressure. We’ve trained more than 600 people face-to-face and 2500+ online across the globe, and started a movement that encourages curiosity and learning, not judgment and blame.

If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider the first step in developing your knowledge and awareness by taking the Essentials of HF for Divers here website.

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.