Just another brick in (under) the wall...taking action

Aug 01, 2018If you want to do something new which improves your safety or performance, how committed are you? If you see something shiny, how easy is it to buy that compared to making a change to your habits or behaviours? Which is likely to have a greater effect on your diving?

Three weeks ago I met Isabel, a business coach specialising in branding and marketing, with a view to working with her. She had been recommended to me as a coach who has the knack of pulling coherent ideas from the free-flowing discussions and coming up with a clear message regarding an offer, branding and identity.

As Isabel and I sat there waiting for our coffee to cool down and talking about the future, she asked me a really important question. “On a scale of 1-10, how committed are you to making a difference to your business so that you can grow and get to where you want to be.”

I said "9". I also added that given the time I put into developing human factors and non-technical skills programmes for the diving community, my wife would say I was a 10!

"Good, because I only deal with people who are a 10.” she responded.

We started working together a week later.

During the meetings we have had since then we have discussed the data, information, knowledge and experience that I possess from 25 years in the RAF as aircrew and a systems engineer, months of working offshore delivering a human factors/non-technical skills programme, hundreds of dives around the globe exploring wrecks and seascapes and photographing them, the multitude of books I have read, the papers and articles I have written for magazines and journals and the courses I have developed and taught.

My take was that knowledge is developed from information which comes from data. Isabel had something critical to add to this which would change my view.

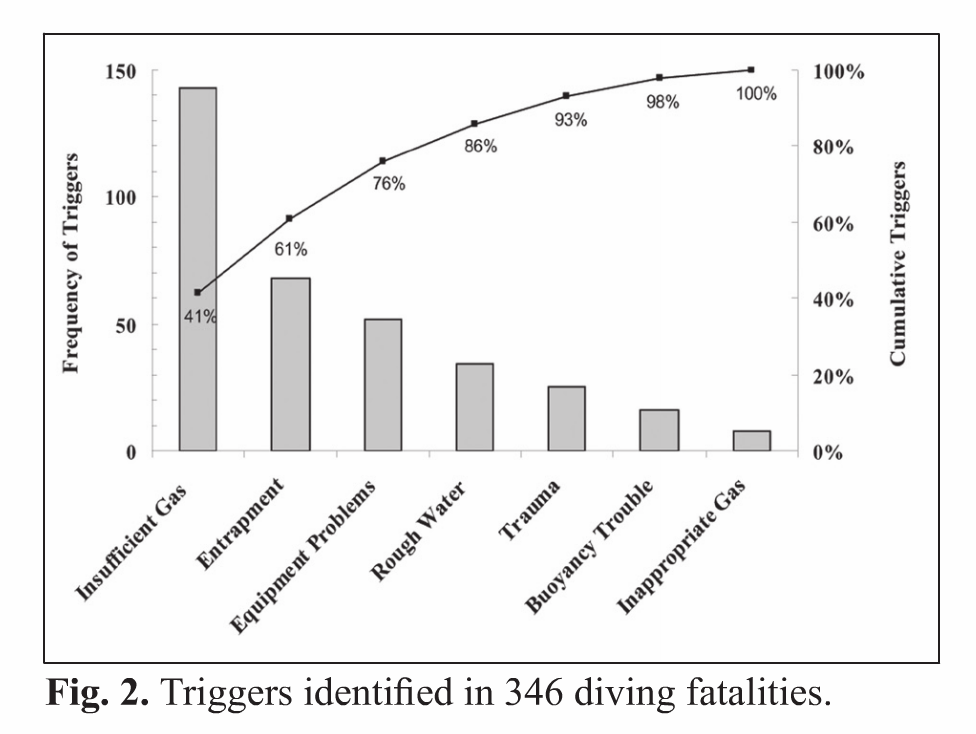

The data I am referring to are single points and/or observations which exist on their own, in the context of diving, these could be the pressure laws we must follow or the specific incident/accident outcomes e.g. running out of gas. The information is then created when those single data points and observations are brought together into a report, a book, research paper or general presentation/teaching points e.g. 41% of fatalities which DAN investigated had a trigger which was insufficient gas.

I then said I believed knowledge is about pulling the information together into a coherent manner which relates to a specific context. Examples of these include the documents I use to create my training and coaching resources like CAP 737 (civil aviation), IOGP Doc 502 (Oil and Gas) and the Non-Technical Skills for Surgeons handbook (healthcare - surgeons) which take the research from world-leading academics and operational teams and apply it to a specific domain so that it is relevant for that domain. In the diving context, these are the online, webinar and face-to-face human factors or non-technical programmes I run or the case studies I write.

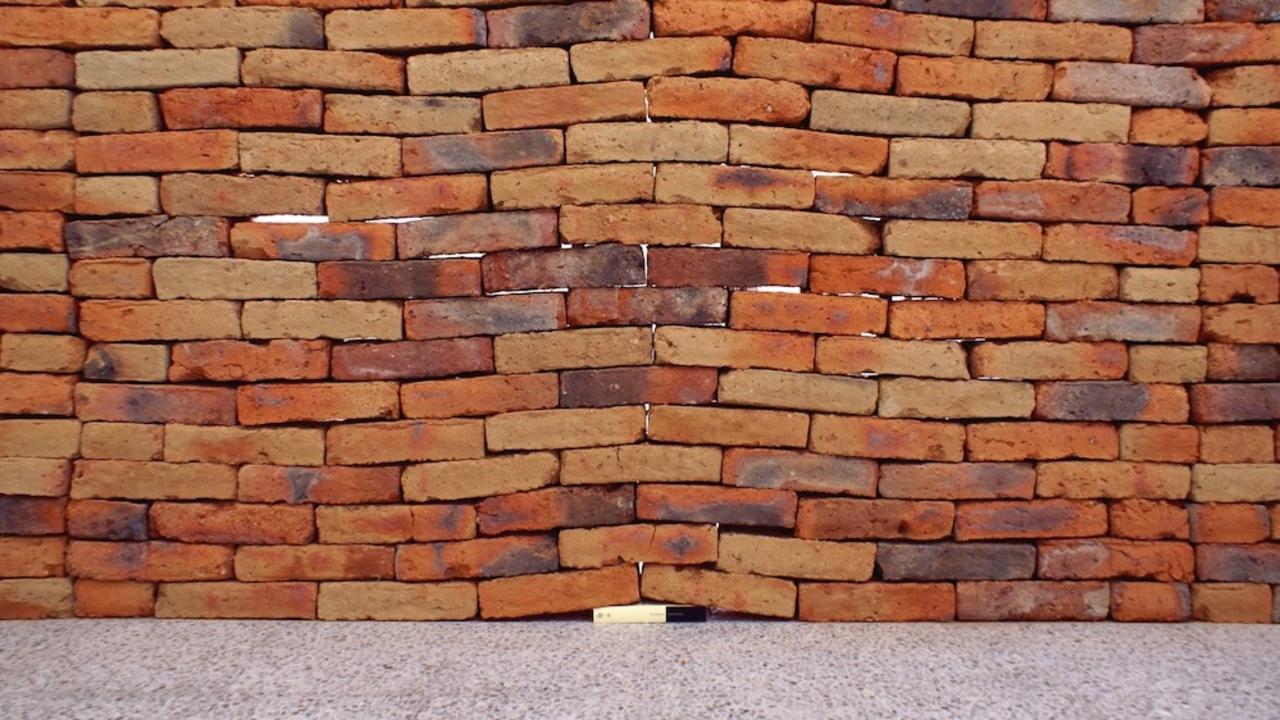

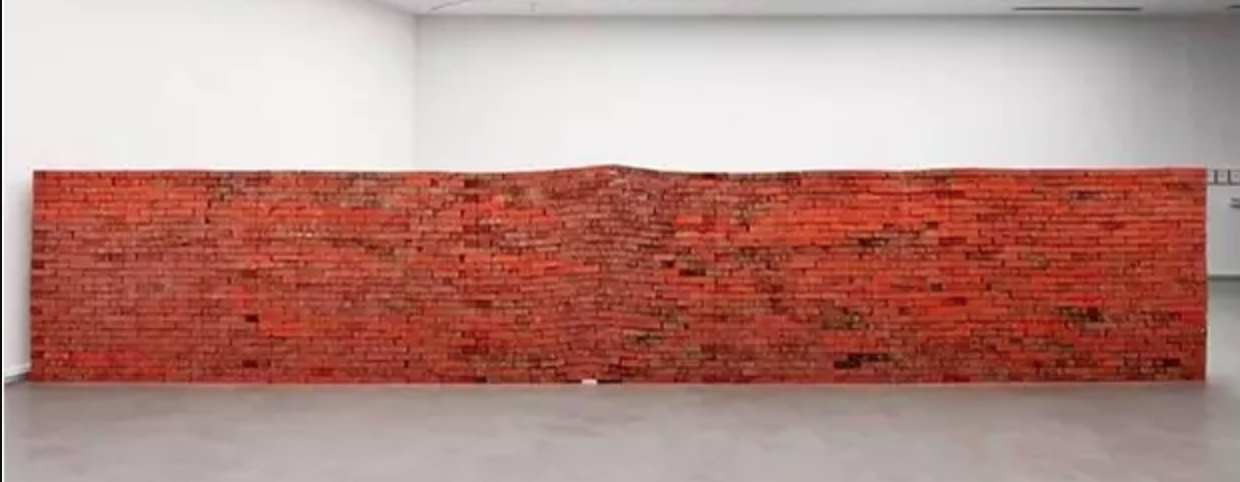

Even though this popular cartoon from @gapingvoid shows that knowledge comes from connecting the informational dots, it was clear from my discussions with Isabel that having all this knowledge is of no use if you don’t actually act on it. Like the book under the wall in the title image. The book contains data, information and knowledge, but on its own, it doesn't create action.

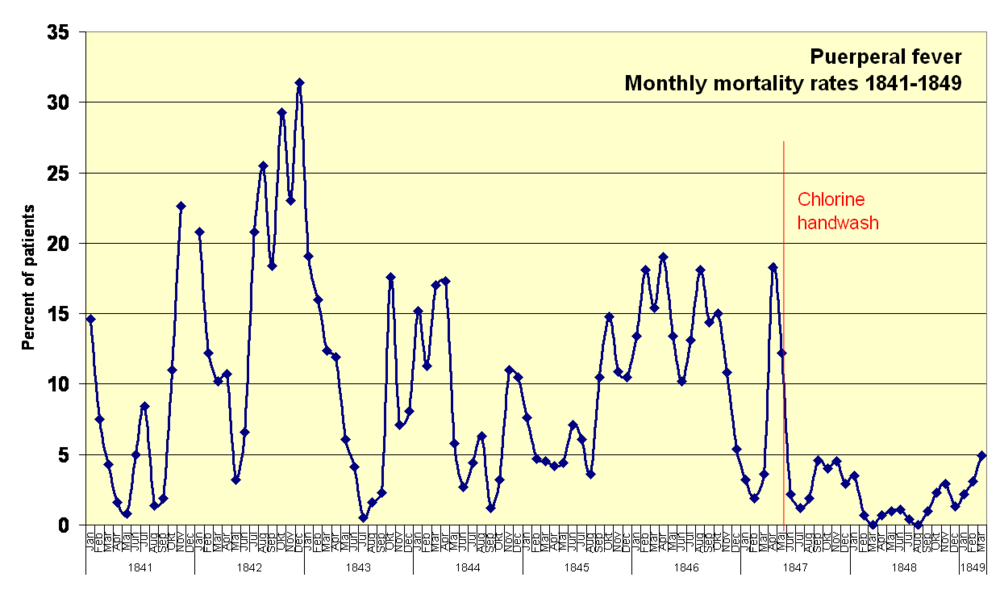

We can create action if we apply the knowledge in the right place, as ‘The Castle’ by Mexican artist Jorge Méndez Blake shows. Interestingly, disproportionately large changes can be created from such small actions. No mortar or adhesive was applied during the construction and so great care was needed to ensure it remained upright and intact, this is despite the disruption caused by the book. What can be immediately seen is that the book, despite its small size, has created a change and distorted the wall, an effect which the artist had planned for. The same can be said of the World Health Organisation Safe Surgical Checklist which reduced mortality rates by 47% and complications by 37%, or of Semmelweis's hand-washing protocols which cut mortality rates massively. However, it was the action that created the change and in the case of the checklists, it was empowering nursing staff to prevent the surgical activity from proceeding until the checklist was complete which made the difference, not the presence of the checklist itself.

Puerperal fever monthly mortality rates for the First Clinic at Vienna Maternity Institution 1841–1849. Rates drop markedly when Semmelweis implemented chlorine hand washing mid-May 1847

So what?

In diving, there appears to be a resistance to using simple tools like briefs, debriefs and checklists to improve safety. The development is not because of a lack of information or knowledge, it exists in other domains with plenty of research to support their use, but rather because the action doesn't take place. One of the key feedback points from the end of the classes I run is the power of briefs and debriefs to improve performance, and the value of a checklist to ensure that critical steps are completed when under stress (and what happens if you decide to shortcut them when you are pressured).

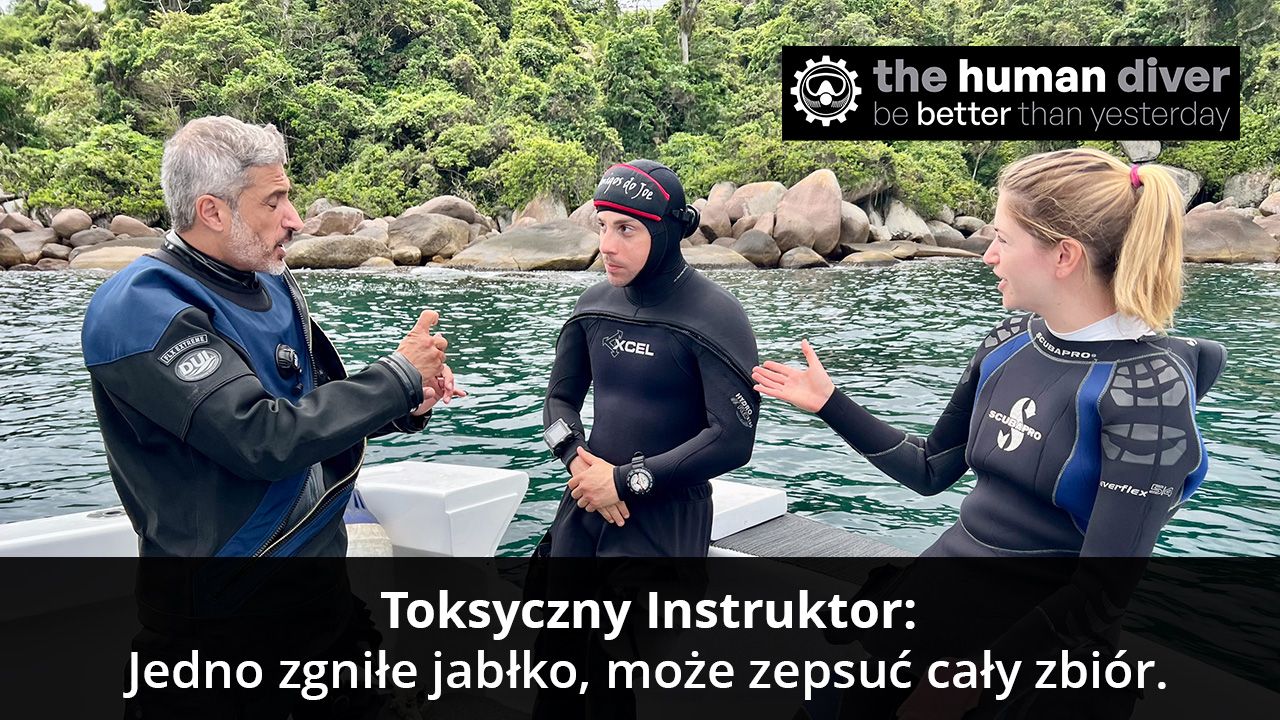

Furthermore, understanding how we make decisions (good and bad) is often ignored because it is easier (and common) to blame an individual for not taking responsibility rather than look at the system in which they are part of. Numerous published research papers in high-risk industries show that if the same continual failures are happening at the 'sharp end' (the 'workers' conducting the activity and following the 'rules', procedures and processes) then it isn't likely to be a 'sharp end' problem and that systemic failures are at hand. The problem in the diving industry is that there isn't anyone able to make systemic changes, other than the agencies and statistically diving is 'safe' so why would they do this. With the constant pressure from litigation, it might be the insurance companies who make the decisions and this will have massive implications.

Risk (or uncertainty) is managed, in the main, by the individual. They need to take responsibility for their actions. However, as shown in my previous article, making decisions on incomplete information is never simple and only by having an effective feedback mechanism are we able to learn from our own or other's mistakes (and successes). The tide is turning regarding posting about the mistakes that we make, but there is no common repository which can be referenced as a learning site.

Finally, there is a concept called 'differencing through distancing' which is where we come up with all sorts of reasons why someone made a mistake but that you wouldn't make that same mistake because you use a different piece of equipment, or you dive in a different way, or that you use different decompression algorithms, and yet most of the issues are based around decision-making, communication and teamwork (or lack of it).

We are all human. We are all fallible. And we all make the same mistakes.

So you have may have read books, watched video clips and presentations and been taught skills, but have you actually applied what you have learned? And consistently applied it. Sometimes that action means getting someone else in who can take the information you have, create knowledge from the dots you have and then hold you accountable to ensure the action happens. For that, I have Isabel, my coach.

What about you? What are you going to do to change the create action from the data, information and knowledge you have?

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a niche company focused on educating and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website.

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.