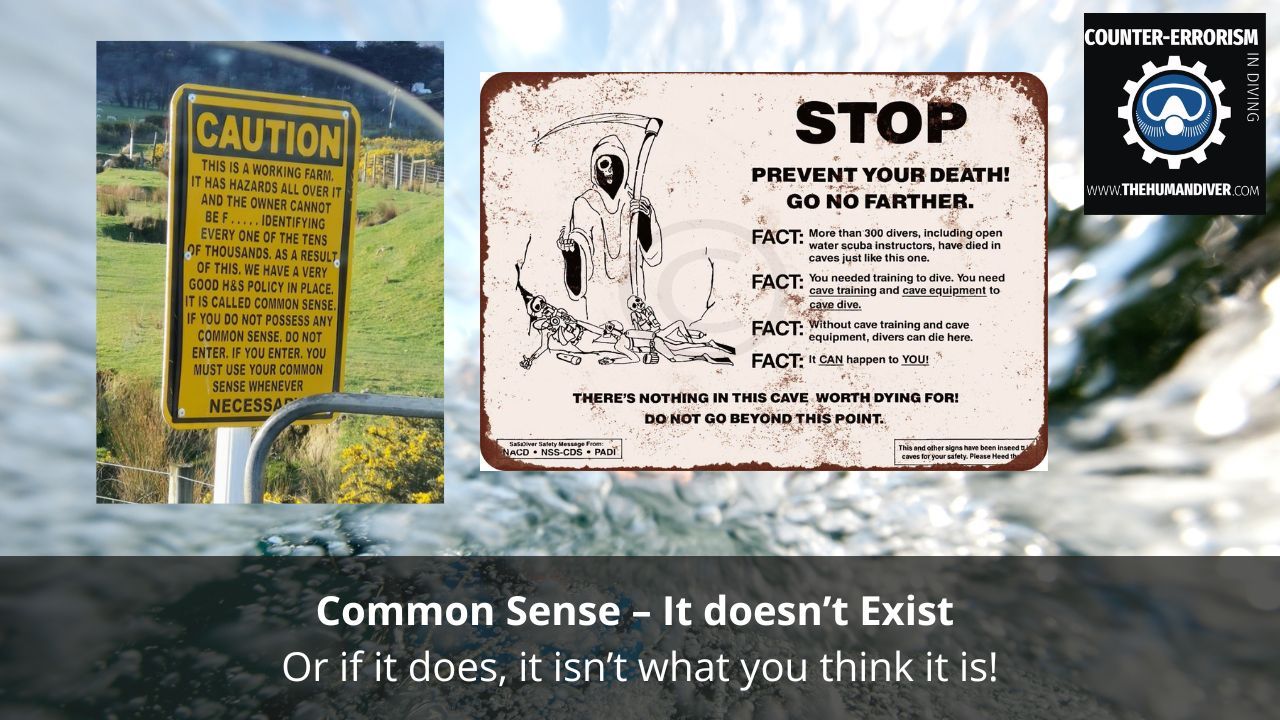

Common Sense – It doesn’t Exist: Or if it does, it isn’t what you think it is.

How often have you heard the phrase, normally after something ‘obvious’ has gone wrong, “They should have used their common sense” or “Has common sense died out?” To you (or those observing the outcome) it was obvious that the situation would develop in the manner it did. This is partly because of the hindsight bias, but also has to do with how we make decisions or choices when faced with uncertainty i.e., no guarantee of a particular outcome (especially the one we want!). One of the reasons that the Grim Reaper sign is placed in caves is because it appears to be common sense not to enter caves without training or the right equipment, but there are still divers who do this without recognising the risks they face if something were to go wrong.

How we make decisions or ‘choices’.

There are numerous decision-making models out there, some of which we cover in The Human Diver course materials. At the most basic, we collect data through our senses, process the data and match it against patterns or mental models created by previous experiences, and this gives us a ‘best guess’ option as to what the outcome will be, and we make that ‘decision’. The more experiences and mental models we have, the more accurate our ‘best guesses’ will be. The research from Gary Klein, an expert on decision-making in uncertain environments, has shown that with more models and experiences, we can also make better decisions more quickly than novices do. In this context, novice refers to a specific situation. A consultant surgeon is an expert in their field, but unless they’ve spent lots of deliberate practice diving, they aren’t an expert in diving. Expertise is relevant to the domain.

We construct meaning.

The above section talks about how we conceptually make decisions as an individual. However, we are social creatures and that adds a level of complexity. As we communicate with each other about what we’ve seen, heard, smelt, touched, felt emotionally, and tasted, we start to add these narratives to the existing mental models and experiences we have, building our library of how to interact with the world and how to make a ‘best guess’. We should recognise that meaning isn’t out there, we construct it from everything we’ve experienced previously and the feedback we’ve perceived. Constructing meaning from experiences is something else Klein picked up when studying fire ground commanders and military tactical leaders. These teams created a shared understanding of what might happen when they encountered a certain situation, so they knew what to do without really thinking about it – this is known as naturalistic decision-making. The teams were creating a common model of a ‘sense’ about what to do.

Tribes and tribal learning

There are a number of things which have reduced our ability to develop and then apply ‘common sense’ in diving. If you go back 30 or 40 years, the sport was undertaken by a relatively small group of individuals who would learn in an experiential (trial-and-error) manner, often under an apprenticeship model, and feedback was provided in a short period of time. However, sometimes this feedback was in the form of dead divers because the boundary of ‘safe’ wasn’t well known at the time. People knew each other personally, and they told stories about stuff going well, and they also told detailed stories of accidents. Michael Menduno’s aquaCORPs provided an opportunity to share these stories which allowed the learning to go beyond word-of-mouth within the small teams that existed. While there wasn’t a formal knowledge of human factors and decision-making, those involved were learning by doing and reflecting on the doing. This is why some in diving say that ‘human factors in diving’ is just ‘common sense’.

As diver education has developed, and the number of divers has grown massively, then the tribal learning that takes place has declined. The context-rich stories that were shared aren’t as prevalent and this means the opportunity to learn by proxy is reduced. This is despite the social media outlets that are available which provide an opportunity to share stories to thousands of people. However, as more channels spring up, the communities and tribes become fragmented. To gain social media ‘algorithmic value’, the stories have to be emotive and controversial, and this reduces the learning factor as we focus more on the people involved than the context. Sharing might also be reduced because of a fear of legal action and this is something I am exploring as part of my MSc research at Lund University.

A major factor I believe that leads people to not share near-misses and learning stories is because of the fear of retribution via social media. Unfortunately, social media provides an easy opportunity to throw metaphorical rocks at those who were ‘stupid’, ‘Darwin Award Winners’ and lacked ‘common sense’. The Darwin Award winner is not relevant in the diving context (or in most safety situations TBH), because we have not adapted to diving, especially more complex activities like cave diving or rebreather diving.

With hindsight, it is easy to join the dots and spot the ‘common sense’ that was missing.

When we face a choice or a decision which involves a level of uncertainty, which is most of the time, to be honest, we are managing uncertainties using heuristics and biases (as described in last week’s blog). If we haven’t encountered a situation before, how would we know what the outcome is likely to be? When we shared stories within our group, our tribe, and our team, then we could learn from others’ experiences. We made sense via a shared model of what was ‘good’ and what was ‘bad’. We constructed a ‘common sense’.

Practical Wisdom

Instead of thinking about ‘common sense’, maybe we should be thinking more about using the term practical wisdom. This has broadly the same outcome – we are using collected and collective knowledge and experience to help us make sense of the world, leading to a more effective decision and associated outcome. However, it isn’t quite so judgemental as the term ‘common sense’.

This TED talk from Barry Schwartz describes the topic in a bit more detail

Get the debrief done!

One of the consistent ways in which teams (and individuals) get better and build practical knowledge is through debriefing and reflection – it was a key factor in Klein’s work on teams and decision-making when operating in uncertain situations. It doesn’t matter what high-performance team you are observing, they will have some form of structured debrief or after-action review which is conducted in a psychologically-safe environment. Where learning, not belittlement or shaming, is the key. The focus of the comments is on the actions and behaviours of those involved, not the individuals themselves – depersonalise the feedback. Jenny and Mike ran a webinar at the end of 2022 which replicated a presentation Mike and I gave at OzTek 2022. You can view it below.

You can also download The Human Diver debrief guide from here www.thehumandiver.com/debrief

Summary

If you hear someone say 'that was just common sense', ask them if they've encountered that situation before, or read about it and really understood the context and outcomes. Then ask them if the person involved did what made sense to them at the time given their goals, their knowledge, their experience, and whether they'd encountered the same situation before (and maybe had a good outcome). Our appreciation of an adverse outcome is heavily clouded by hindsight bias and the fundamental attribution error, leading us to put ourselves in the shoes of the other person but with our knowledge of both the situation and the outcome, without considering their local rationality. If you've not encountered a situation before, how do you know what is 'sense' let alone 'common sense'?

Common sense is not common. It is a shared understanding within a group of individuals, a shared understanding which includes the context and likely outcomes, and this allows individuals in the group to make more reliable decisions. If we aren't able to share stories of the complex environment we are operating in, i.e., incident stories, how do we think common sense is going to develop?

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a niche company focused on educating and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website.