Decision Making: Normalisation of Deviance in Rebreather Cave Diving

Jun 25, 2025It is important for all divers to be aware of the conscious and unconscious decisions that they take in planning and executing dives. If risky behaviour does not have any obvious adverse consequences, it is very easy for the unsafe act to become the new normal. This is especially true within high-performing teams in cave and technical diving, where it easy to drift, especially if the team is small and not subject to many outside influences.

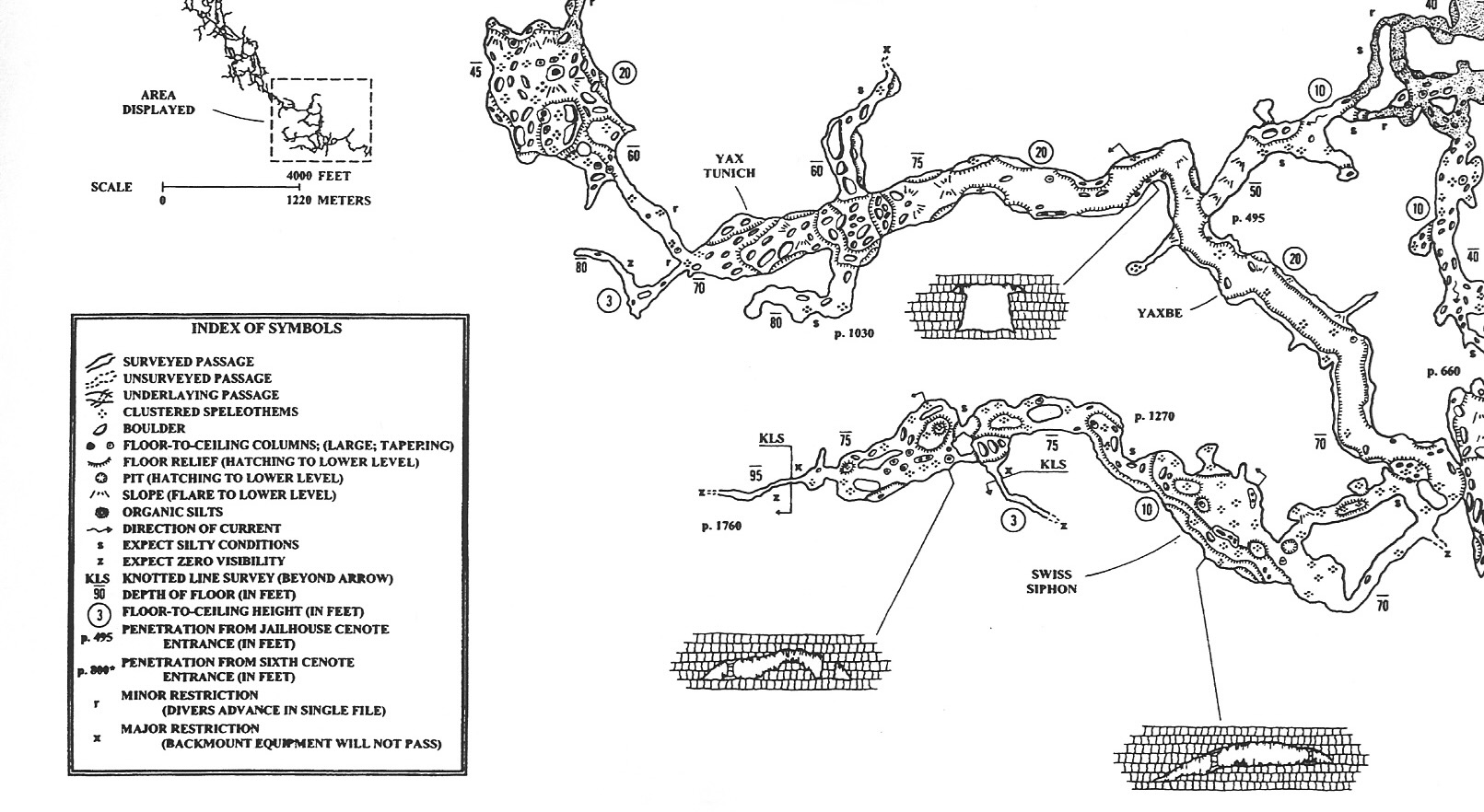

I had an interesting discussion with a cave rebreather student earlier this year that reminded me how easy it can be to normalise breaking the rules, and why it is important to be cognisant of decisions that can lead to drift. We were planning a complex hub and spoke dive in Cenote Jailhouse. Most agency standards for CCR Cave do not require especially long or complex dives, and many CCR Cave classes involve pretty simple dives that could easily be completed on open circuit. I believe that when learning to use a rebreather in the overhead environment, you should use the full capability of the equipment, and we were planning a 4-hour dive with lots of navigation.

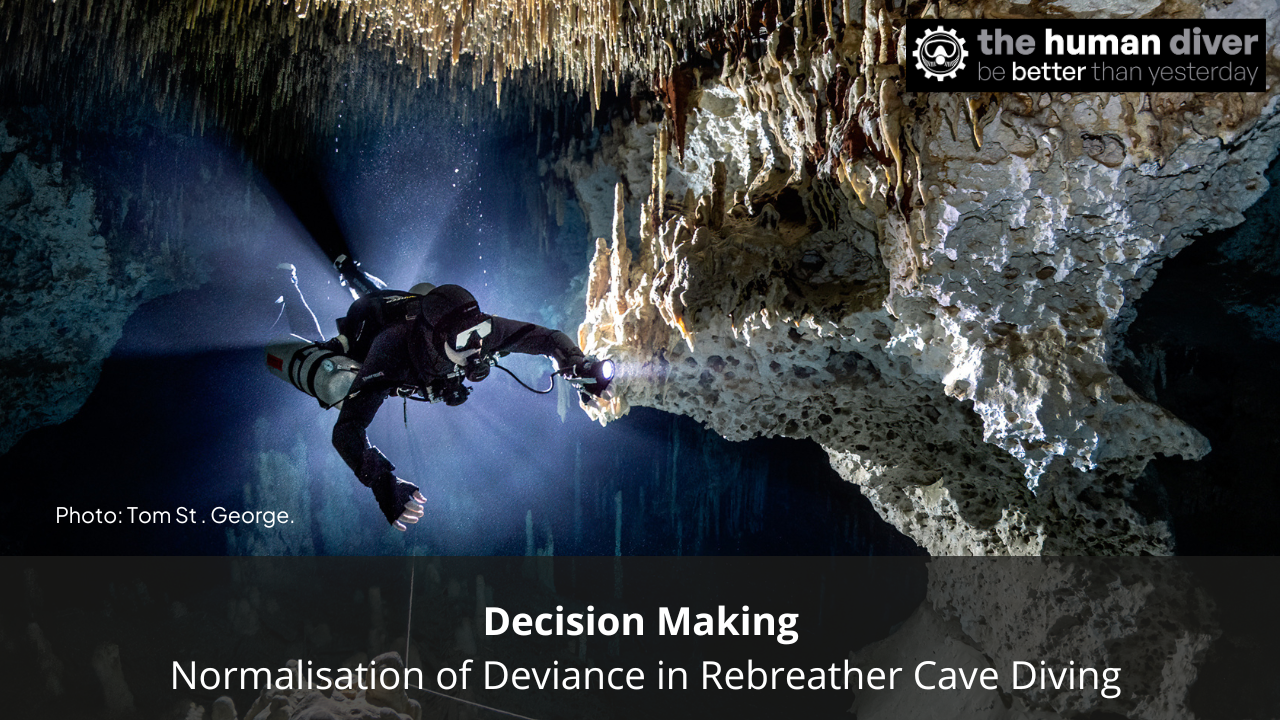

(CCR Diver in the Swiss Siphon)

(CCR Diver in the Swiss Siphon)

We decided that it would be cool to have a look at part of Jailhouse that is not visited that often, specifically the area of cave that loops back towards the mainline, going left at the T intersection in the Swiss Siphon. Most teams have open circuit gas/time constraints and plan to visit the highly decorated longer section of the Swiss Siphon area, so don’t bother swimming up this short but very pretty passage.

The end of the line of this section of cave is very close to the line where divers enter the Swiss Siphon, not much more than a couple of body lengths, and in very obvious sight.

As we were planning our dive, we discussed how we would navigate and mark this section. At this level of training, the relationship is much more based on mentorship than autocratic instruction, and it is rewarding to have honest discussions within a psychologically safe environment. The importance of psychological safety is not emphasised enough in diver training. Feeling included, feeling safe to learn and make mistakes, being able to contribute and being able to raise concerns and challenge the dive plan are all elements of this, and all contribute to enhancing safety and enjoyment.

Psychological Safety Sign at Underworld Tulum

Psychological Safety Sign at Underworld Tulum

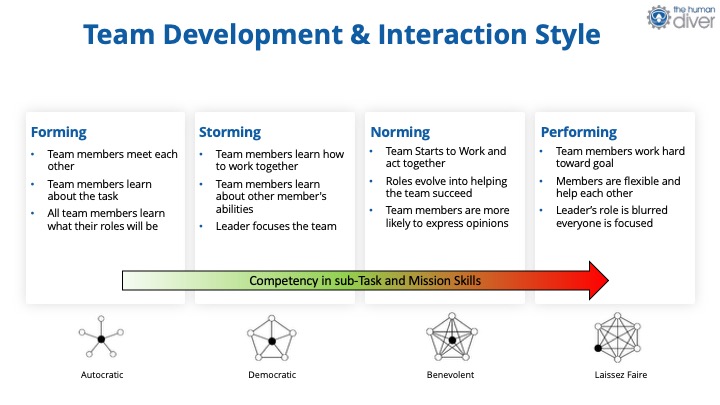

This mentorship approach is also related to Tuckman’s work on how teams develop. Within higher-level cave or technical classes, leadership from the instructor is in the “norming” and “performing” phase, with blurring of roles and a benevolent or laissez-faire leadership style.

My student initially suggested swimming around the loop, rejoining the line we had already swum over without installing a line and then continuing to the T, where we would turn right and continue the dive. This seems like a reasonable approach, given that we would have swum that section of passage a few minutes before, and we would have rejoined the route right next to our clearly marked spool. However, it would break one of the primary rules of cave diving – the requirement to have a continuous guideline back to safety at all times. In this instance, the chances of any negative consequences are minuscule, the gap between lines is small, visibility is excellent, and we have an experienced team with a huge amount of diving resources and more than triple the amount of gas needed to get home, even if our rebreathers failed simultaneously. This is exactly the sort of situation that can lead to a deviation from established safe procedures being normalised. Once we accept that breaking a protocol is acceptable, then the possibility of further drift increases. If doing a 3m visual jump is OK, and has no adverse consequence, then why not do the same thing when the gap between lines is 5m, or 6m, or 10m, or if the visibility is slightly degraded.

We discussed this option and decided to return the long way round!

Staying within the rules is not easy when the margins for error appear small or there are other biases involved, such as the sunk-cost fallacy. The normalisation of deviance isn't about breaking the rules per se, it is more about the social acceptance of the gradual erosion of the standards that have been set. And because we are social creatures, once the erosion has started, it is much harder to recover the situation because you've already got 'evidence' that shows nothing wrong happened when you deviated the last time.

Having clear standards within the team makes it easier to call out drift. Having a psychologically-safe debrief allows you to identify where gaps between what should have happened and what did happen to be identified and be corrected. Psychological safety isn't about being nice, it is about being honest with each other, even if that is difficult.

Lanny Vogel is a full-time cave, technical and rebreather instructor based in Tulum, Mexico. He is the owner and lead instructor at Underworld Tulum and is part of the local cave line and safety committee. He regularly speaks at dive shows on cave diving and human factors topics and has been a passionate advocate of the integration of human factors principles into dive training for many years.

How many times in your own diving have you made seemingly small compromises that could easily become the “new normal”? Being aware of how we make decisions, including exploring the normalisation of deviance, is a key part of the online Essentials and the “in-person” Applied Skills classes from The Human Diver. Click here to see what classes are available in your area.

If you're curious and want to get the weekly newsletter, you can sign up here and select 'Newsletter' from the options

Want to learn more about this article or have questions? Contact us.