Were you lucky or were you good?

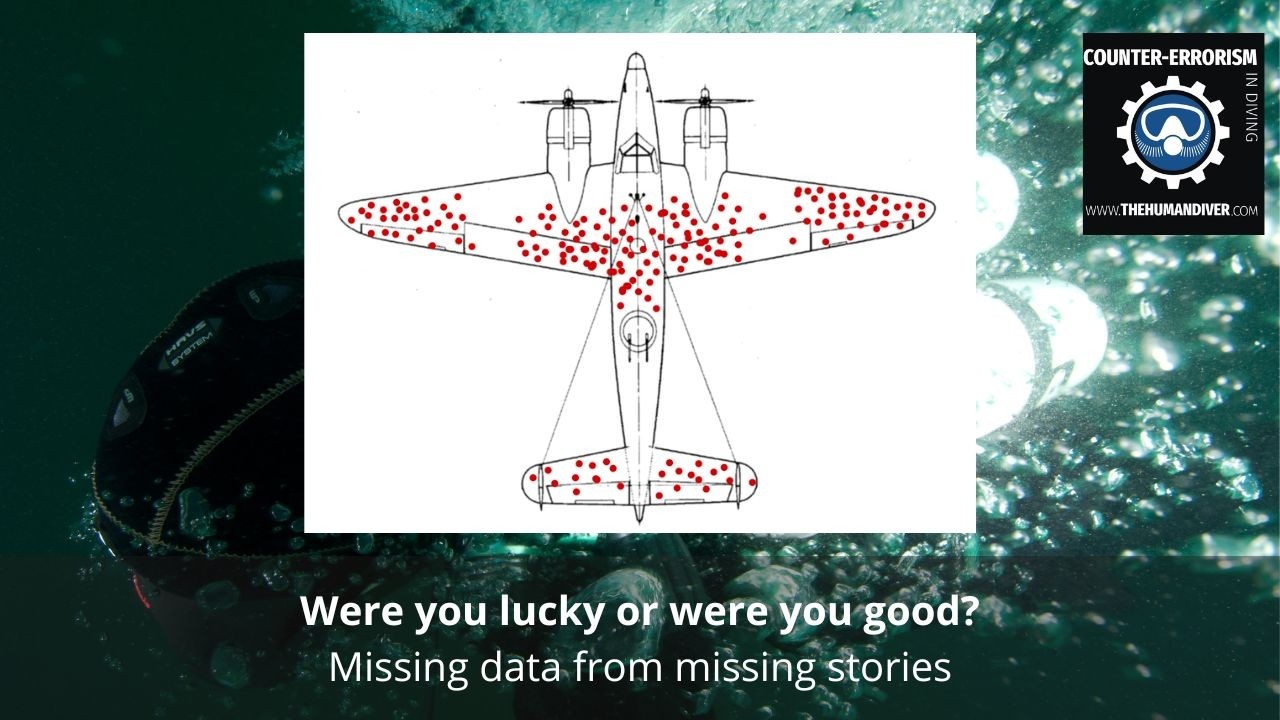

Recently multiple people have sent me the story of Abraham Wald and the World War II bombers. This story described how during World War II analysts worked on improving the protection and survivability of bombers by determining the best location to place additional armour. Despite significant analysis from existing engineering and survivability teams which worked out that armour should be placed in the damaged areas, Abraham Wald from the Statistical Research Group (SRG), determined that the best place wasn’t where all the bullet holes and flak damage was located, but rather the armour should be placed where the damage hadn’t happened.

The reason for this counter-intuitive decision was because those aircraft that made it back could likely sustain damage in these specific locations and still survive, but the damage in the ‘clear’ areas likely meant that that area was critical and any damage would be catastrophic, leading to the aircraft and crew being lost. This activity demonstrated the effectiveness of a fledgling area of research called Operational Research which required researchers and analysts to look wider than just the apparently obvious when it comes to the data that is available. This page has many examples of where operational research has value in marketing for example.

So how does this relate to diving?

Firstly, there are many factors which relate to success in diving covering equipment, training, the physical and social environment, non-technical skills and a pinch of luck. Regarding improving the survivability of the aircraft, the technical design of the aircraft wasn’t necessarily enough, it needed operational feedback to enhance it because engineers can only design and model so much. When consistent failures occurred, it wasn’t enough to put patches over the problem, there was a much deeper look at how to create success i.e., bring the aircraft and crews back. In the context of diving, this relates to the need to have data concerning not just why incidents/accidents have happened, but also the factors which led to a successful outcome.

During the two-day courses run by The Human Diver, we ask each of the students to talk about a story where something went wrong or exceptionally well. Even if the divers had had something go badly wrong, they must have done something or multiple things that allowed the situation to be recovered otherwise they wouldn’t be in the class! In the discussions that follow, we explore the reasons for this ‘going well’ and most of the time it relates to a combination of technical and non-technical skills. However, in some cases, luck played a significant part in what happened. The problem with successful outcomes without reflection on how success was achieved, is that the success could be down to luck rather than skills. “Were you lucky or were you good?” If you were good, what did you actively do to control/direct the situation and end up with a successful outcome? An easy way to apply this learning process is to run an effective debrief which looks at four key questions.

- What did I or we do well?

- Why did it go well?

- What do I or we need to improve on?

- How will we do that?

While the debrief link above will explain more about how to run a learning-focused debrief, the key questions are not the observations (Do well? Need to Improve?) but rather it is the analytical questions (Why? How?) that need focus. Observations are easy, thinking is hard!

Secondly, survivorship bias! This is where we look at individuals who have made it past some selection process and we don’t look at those who didn’t because the latter doesn’t appear to be important. In diving, this could be about the dive centres who are successful or the dive instructors who have made a successful career out of the diving industry, but not looking at the thousands of instructors who leave the industry because of poor pay, disillusionment, a passion which is exhausted or some form of injury. “Living the dream” is a statement often placed with images of diving professionals in nice locations, with decent gear, and smiling guests, and yet we don’t see the nightmares that some instructors encounter because they are financially trapped in a location because the pay is so bad that they can’t leave. Combined with sunk cost fallacies and the associated criticism that comes from making poor decisions, those involved don’t want to talk about what life is really like. The same thought process could apply to divers who leave the sport early. Just because there is a potential stream of new divers coming in, it doesn’t mean we should ignore those who have left.

Focusing on human factors and non-technical skills in diving

When diving incident narratives are recounted, they very rarely include any reference to context or non-technical skills e.g.,

- how decisions were made by those involved,

- how (mis)communication occurred between the parties,

- how the team dynamic developed and problems that were present,

- what the level of psychological safety was like,

- where the attention of those involved was pointed (rather than saying situation awareness was lost),

- how the leadership style used influenced the outcome of the dive or class, and

- ultimately how it made sense for those involved to do what they did.

Because this data is not immediately available, then it isn’t included in the analysis. It takes the analysis of the stories within books like Close Calls and Under Pressure to pull out where these non-technical skills helped those involved survive or succeed but also identifies the presence and impact of error-producing conditions in how incidents develop.

As has been said to me on numerous occasions when I’ve tried to bring the importance of human factors and non-technical skills into diving to support safer and more enjoyable diving,

- “Where is the data that shows HF is important?”,

- “There isn’t any”,

- “In that case, it can’t be that important.”

The absence of data does not mean an absence of a problem. Given that there is considerable data and expertise from high-risk industries such as aviation, healthcare, oil & gas and nuclear, to show how humans operate broadly the same way when in dynamic, changing, and uncertain environments, it would be naive to think that divers and the diving industry is different. Therefore, the reason for the existence of The Human Diver and the instructors within is to show that we should take account of the value that HF, non-technical skills, psychological safety, and a Just Culture contribute to the safety and enjoyment of diving.

To that end, I thank those instructors, dive centres and training agency staff who have recognised the value of human factors and are working to bring it into the industry via their centres and agencies. As JW Goethe said, “Knowing is not enough, we must apply. Willing is not enough, we must do.”. This means that while you personally might know that HF and non-technical skills are a good thing, you have to do something with your knowledge if you want to make a change.

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a niche company focused on educating and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website.