What relevance does Human Factors have to recreational and technical diving?

A comment I often get is "How relevant is Human Factors to my diving and why should I care? I haven't had an accident so far, so I (we) can't be doing anything too wrong"

This is a fair comment but consider that high risk organisations have learned the hard way: using the premise that evidence from the past to determine behaviours in the future can lead to some very bad outcomes. Consider the following examples:

- NASA and the Challenger and Columbia disasters - doing the same things and edging further from accepted standards, a normalisation of deviance, aterm coined by Diane Vaughan. That's a pretty big organisation.

- An Executive Jet crew who forget to remove the gust lock from their jet which meant they couldn't move the control column subsequently crashed at the end of the runway killing all onboard?

- A general aviation pilot who didn't drain the water from his fuel tanks as part of the standard operating procedures and crashed?

- The students and instructor who didn't analyse their gas during a Mod 1 CCR class and consequently the student who bailed out due to having 72% in their diluent and not air. Cause? An O2 top onto air and no analysis due to distraction, confusion, peer pressure and lack of following procedures.

- The diving instructor who dived with out of date cells and due to the voting logic in his CCR, and poor decision making, had an oxygen toxicity event.

- The recently qualified AOW diver who felt peer pressure to help an instructor with 4 OW divers on a dive to 27m and nearly died due to becoming entangled in line and running out of gas.

All of these had human factors at their core and in each case there was no undetectable technical or environmental failure present.

Consider how many times a dive hasn't gone to plan, it doesn't have to have ended in an injury or anything more serious. Now critically examine why it didn't go to plan. Was there even a plan to start with?! How effective were the communications in ensuring everyone knew the plan? Who was 'leading'? What about decisions that were made? Were they just a collection of assumptions based on previous experience or were they discussed? And so on.

Cdr Chris Hadfield in his book "An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth: What Going to Space Taught Me About Ingenuity, Determination, and Being Prepared for Anything" talks about 'sweating the small stuff' for a couple of reasons. Firstly, because in the environment he is in (and potentially the same when diving) you need to consider everything that might go wrong, and that starts with the small stuff. Fix the small stuff and it won't grow into the big things. Secondly "Anticipating problems and figuring out how to solve them is actually the opposite of worrying: it’s productive.”

What about instructors or instructor trainers and how difficult they find it to get their students to develop? Effective communications, and understanding the barriers to them, is essential. On the last course, the use of student-led reflective debriefing was one of the key points picked up by a number of the instructors and was going to be taken to their own training courses.

The challenge is realising that these are all human factors and they will apply to us all, irrespective of knowledge or experience. Even experts make mistakes. The same skills which mean we can be awesome, operating in incredibly dynamic and ambiguous environments, also mean that we make errors. The human is both the hero and the villain and we don't normally find out which until after the event, using the outcome to inform the judgement.

The equipment manufacturers have gone a significant way to improving the safety and reliability of diving, but they can't do anything about the grey matter between our ears. That is something we, as individuals and members of teams, need to improve. It happens by being critical of our own activities, by getting honest peer review, but that peer review cannot be full of platitude. Back-slapping doesn't help anyone improve. Positive criticism leading to development is different to back-slapping. Understanding how and why things went well is essential to development so you can repeat those skills or behaviours the next time you encounter the same or similar environment. Look to your own diving now. When was the last time you had an honest critique of not just your technical skills, but your communication skills, your situational awareness or your teamwork including specific details about how you did?

Are there any published papers about improving diving safety and performance using human factors skills in diving? No, not yet and that is something I am working towards. However, at the bottom of this page, there are plenty of examples of how it works in healthcare including saving considerable sums of money and improving patient outcomes.

Online Mini-Course

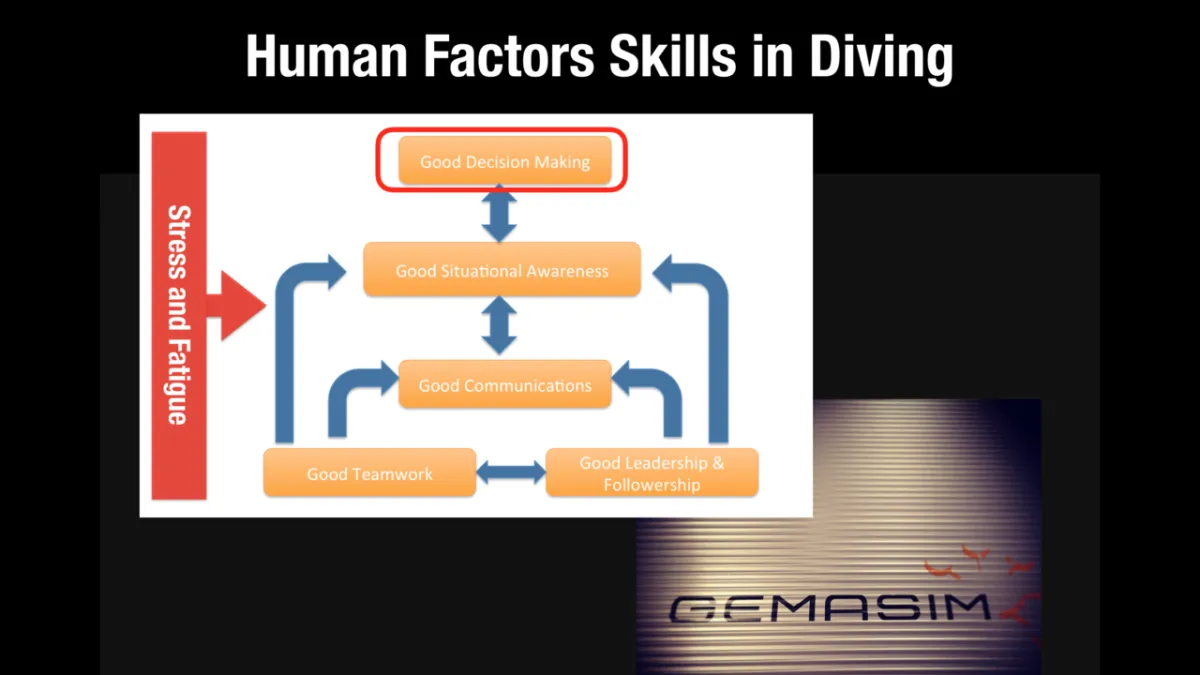

On Friday 16 March 2016, the online-only Human Factors Skills in Diving mini-course was launched (now replaced by the Essentials programme here). It is a 2 hour course delivered in 9 modules of approximately 15 minutes each, covering the six key themes along with a number of specific examples to show relevance and one detailed case study and a summary of the main two-day course. It was developed following feedback from a number of those who have attended the class which went along the lines of "This was an excellent two-day course and one which every diver, especially those in leadership, instructional or technical diving roles should undertake. However, I didn't know what to expect and therefore I didn't realise the true value of the course until I had completed it."

The 2-day Human Factors Skills in Diving Course

This is a two-day course which develops the theory further, but more importantly, uses the GemaSim computer-based simulation package to develop the human factors skills in a dynamic and ambiguous manner. However, the learning really happens in the reflective debriefs afterwards where specific behavioural markers are identified and then each student has to convert that abstract in the simulation to their own personal diving or instruction to provide the relevance.

The skills taught on this course have the same applicability outside of diving, one of the areas which I am keen to show to divers. In fact I am currently working with a local Intensive Care Unit developing their teams using the same core software and theory, only the case studies and examples have been changed to make them more relevant to them.

Relevance?

We are human. We drift. We make mistakes. We can improve. Human Factors are incredibly relevant to any area where excellent human performance is needed, and that includes recreational and technical diving.

Gareth Lock is the owner of The Human Diver, a niche company focused on educating and developing divers, instructors and related teams to be high-performing. If you'd like to deepen your diving experience, consider taking the online introduction course which will change your attitude towards diving because safety is your perception, visit the website.